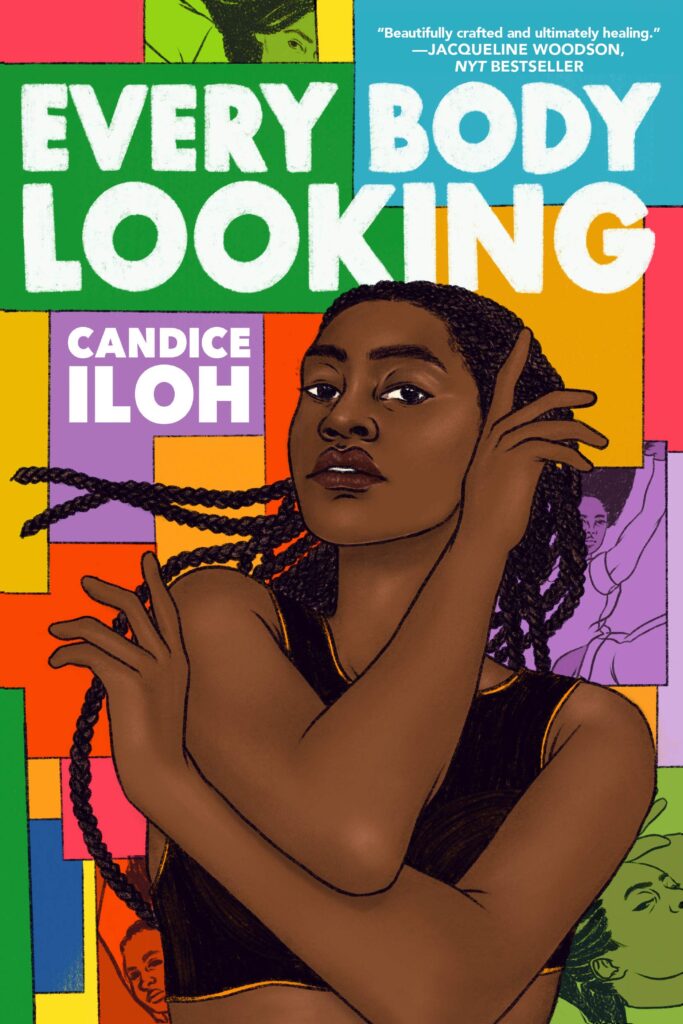

“Every Body Looking” Dances with Verse and Self-Expression

Candice IIoh’s verse novel Every Body Looking begins with Nigerian American teen Ada graduating high school and taking account of how she wants her upcoming college experience to be.

Raised by a strict, religious Christian father and separated from her alcohol-addicted mother, Ada wants to take her life into her own hands but isn’t sure how to go about it. Due to past trauma and her shaky upbringing, she is so focused on other people’s expectations of her that she hasn’t really considered what she wants for herself.

Raised by a strict, religious Christian father and separated from her alcohol-addicted mother, Ada wants to take her life into her own hands but isn’t sure how to go about it. Due to past trauma and her shaky upbringing, she is so focused on other people’s expectations of her that she hasn’t really considered what she wants for herself.

One of the best things this book does to illustrate Ada’s personal journey is include poems that present the standard definition of a word before Ada expresses her own feelings about it. An early example uses the word “safety,” showing how the standard definition of the word applies to the definition of safety that Ada’s dad wants for her as she prepares to go to college. It’s a creative way for Ada to literally define herself by examining what she has been told in order to figure out what she really wants for herself.

Another way the book delves into Ada’s personal journey is through flashbacks to her younger years. Some of these flashbacks are vulnerable and harrowing, since they deal with how people inside and outside of Ada’s family made her feel like her body wasn’t her own. In one painful scene, Ada’s aunt comes to visit and ends up fat shaming Ada and reading her private diary. Another scene shows the police coming to Ada’s door when she is home alone blasting loud music. Although these flashbacks might be triggering to trauma survivors, Ada’s experiences of fatmisia, misogynoir, sexual assault, and parental verbal abuse show just how many systemic forces work to destroy Black girls’ sense of self.

Although these flashbacks might be triggering to trauma survivors, Ada’s experiences of fatmisia, misogynoir, sexual assault, and parental verbal abuse show just how many systemic forces work to destroy Black girls’ sense of self.

At the same time, these flashbacks also show glimpses of a young Black girl with dreams of wanting to dance like no one is watching. One prominent image throughout the book is young Ada drawing a Black girl dancing, who she names “Magic.” Ava’s passion for dance is shown when she remembers being awed by church dancers during a service and how she worked jobs to pay for dance lessons without telling her Dad. The image of the “magic” Black girl dancing is strong because it represents Ava’s hopes and dreams for herself.

It is these dreams that allow the reader to root for Ada as she takes the first steps toward achieving them during her freshman year of college. Like anyone at that age, Ada does make a few mistakes. She settles for a Black guy named Derek who only cares about sex because she doesn’t know she can do better. She takes an accounting course she hates because her dad wants her to. These mistakes are part of Ada’s exploration of her sexuality and her personal goals, and it is interesting to watch her stumble through things, especially since she doesn’t have many people to turn to for help.

In fact, I found myself wishing Ada had more people on her side during such a formative time. The only character who really helps Ava start to figure out what she wants is Kendra, another Black girl with an even bigger passion for dance than Ava. Kendra is delightful to read about because she has a no-nonsense, driven, and confident air about her that ends up having a positive influence on Ava. While Ava and Kendra have a memorable friendship, Ava is also shown crushing on Kendra a bit, too.

Given Ava’s upbringing, there aren’t many moments that allow Ava to explore her orientation other than some interactions with Kendra, rumors that she might “play for the other team,” and secret interactions with another girl that took place when Ava was in second grade. Given the way that heterosexuality is always implied and expected from others, it is nice to see that Kendra is even considering the possibility she might not be straight. Kendra never labels her own orientation, but it isn’t necessary for her, since she is still exploring who she is.

While Every Body Looking was mostly enjoyable, the ending fell a little flat. Without getting into spoilers, we see Ava make a few decisions for herself and for her future at the college, but we don’t clearly know what the results will be. Maybe this open-ended conclusion represents Ava finally putting herself first, even if she doesn’t know where she will end up.

All in all, Candice IIoh’s Every Body Looking dances with verse and self-expression that will surely encourage readers to keep trying for their dreams.

The Afro YA promotes black young adult authors and YA books with black characters, especially those that influence Pennington, an aspiring YA author who believes that black YA readers need diverse books, creators, and stories so that they don’t have to search for their experiences like she did.

Latonya Pennington is a poet and freelance pop culture critic. Their freelance work can also be found at PRIDE, Wear Your Voice magazine, and Black Sci-fi. As a poet, they have been published in Fiyah Lit magazine, Scribes of Nyota, and Argot magazine among others.

Photo by Anna Shvets from Pexels.