Take Away

How a Renovation in Cuba Connected Me to My Chinese and Cuban Heritagesby Katarina Wong

It was the tiles that clinched the deal.

My apartment search in Havana had grown cold, and I’d just about given up when the realtor called.

“A new listing just came on the market that I think you’d like,” she said.

We hoofed it up four long flights to the top floor and entered a living room with fourteen-foot ceilings and balconies that opened up to a spectacular view. It spanned from the Capitólio, a near-identical replica of the U.S. Capitol building, across the lush green treetops of the Granma Memorial and out to the malecón, the famous sea wall that marked the edge of the island.

We hoofed it up four long flights to the top floor and entered a living room with fourteen-foot ceilings and balconies that opened up to a spectacular view. It spanned from the Capitólio, a near-identical replica of the U.S. Capitol building, across the lush green treetops of the Granma Memorial and out to the malecón, the famous sea wall that marked the edge of the island.

But it was the cement tiles that ran the length of the space like an ornate rug that caught my imagination. Original to the building, one pattern of interlocking brick red, forest green, and ochre delineated the living room from the rest of the apartment, while a different configuration filled the other rooms. I thought about how generations of daily lives had polished them to a silky shine.

It was January 2015, only a few weeks after President Obama announced a reopening of relations between the United States and Cuba. The optimism this announcement ushered in was unprecedented, and I wanted to be part of what I hoped would be a new chapter for Cuba. I wondered too if I might find the next act of my story. I hoped to better understand my Cuban roots and maybe even find my place here—literally and figuratively.

This curiosity was sparked by a long-held feeling that I was a cultural imposter. Despite having visited my mother’s family in Cuba dozens of times—the first as a child in 1979 during the Cold War—I felt like the lite version of my Cuban relatives who lived in Miami, lacking any real sabor and sweetened artificially. English was my native language, not Spanish; I grew up in Florida, but not in the Cuban ex-pat community full of its rituals and large family gatherings; I never had a quinceañera, nor did I know who the Three Kings were until I was long past the age when I could expect gifts from them.

So, after all of these years, I found myself standing on the tile floors of a nearly century-old building in Habana Vieja, the oldest part of Havana, saying yes to the purchase.

So, after all of these years, I found myself standing on the tile floors of a nearly century-old building in Habana Vieja, the oldest part of Havana, saying yes to the purchase.

Even though the apartment appeared solid to me, my contractor advised me to do a complete renovation and correct any underlying problems. He stripped the cement ceiling and walls down to the metal beams and fixed hidden leaks, upgraded the plumbing, and ran new wiring. I also changed the floor plan to make it more open and welcoming, but one thing I didn’t touch was the original floor. In redoing the bathroom, however, I learned my contractor needed to remove the ceramic tile floor to rerun plumbing lines. It was an opportunity for me to lay a new one, and I wanted cement tiles to complement the rest of the apartment. Like most supplies in Cuba, the challenge was where to find them.

Cuban tiles—referred to losas hidráulicas or mosaicos—were first brought from Spain in the late 1800s, and although Cuba became home to the largest manufacturer of cement tiles in the world within a few decades, by 2015 all of those factories had disappeared. Thanks to a Canadian acquaintance who was in the midst of renovations himself, I eventually found the lone fabricator of losas hidráulicas in Havana.

Cuban tiles—referred to losas hidráulicas or mosaicos—were first brought from Spain in the late 1800s, and although Cuba became home to the largest manufacturer of cement tiles in the world within a few decades, by 2015 all of those factories had disappeared. Thanks to a Canadian acquaintance who was in the midst of renovations himself, I eventually found the lone fabricator of losas hidráulicas in Havana.

Walking into the showroom was like seeing the greatest hits of Cuban flooring. I recognized many of the patterns on the large panels displayed on the walls. There were the fat-petaled daisies against a background of dusty pink I’d noticed in a friend’s home; medallion patterns from a nearby hotel; and even designs from my own apartment. For the bathroom floor, I settled on a black, gray, and white geometric pattern that complemented the white bathroom fixtures.

While there, I was invited to see how the tiles were made. The saleswoman led me down a narrow staircase to the workshop where an artisan was attaching a metal mold to a twenty-by-twenty-millimeter (about eight-by-eight-inch) cement slab. The mold was divided into sections, and he filled them with liquid cement colored with mineral pigments. When the pattern was complete, the tile would be put through a press, then soaked in water to set the colors. After drying, each was not only a handmade piece of art, but one with a lifespan. I learned that the hand-poured layer (about four millimeters thick) corresponded to about a century of wear and tear—of children growing into adults, of fiestas, of families expanding and contracting.

I also noticed a curious thing. When Cubans made similar home improvements, many opted for mass-produced ceramic tiles made in China instead of traditional cement tiles. I’m sure a big factor was cost. While a dollar per cement tile was a bargain for outsiders like me, a dollar represented one twenty-fifth of the average monthly pay in Cuba. I also wondered whether having shiny new tiles seemed more exciting than keeping the faded cement ones they were used to living with. Perhaps it was like an American updating an avocado-green 1970s kitchen with clean white subway tiles and stainless steel appliances. I understood the impulse, but it broke my heart to see old, historic tiles covered over.

Even on an island so cut off from outside goods, China’s inexpensive, expendable products had come ashore, and with them a business model that favors quantity over quality, desire over satisfaction. This disposability ran contrary to what my Chinese father had reminded my sisters and me about the longevity of that side of our inherited culture and the inventions that continued to reverberate hundreds, if not thousands, of years later.

As a child, he’d prompt us with bedtime recitations of the glory of our ancestors’ ingenuity.

“Who invented gunpowder?”

“The Chinese!” my sisters and I would say, a chorus of little voices chirping in unison.

“Printing?”

“The Chinese!”

“Paper?”

“The Chinese!”

“Noodles?”

“The Chinese!

The disparity between those mass-produced tiles and the history my father was so proud of stung as I tried to make sense of what was lasting and what was fleeting about my Cuban and Chinese cultural inheritances.

One evening back in New York, I had an epiphany. As I splayed out a carton that held my vegetable lo mein, I noticed the curious angles and cuts that, when folded, came together in a shape known the world over. Here was something designed to be disposable but that was still iconic. What if I juxtaposed Cuban tile patterns on them—not as cartons, but as flat surfaces. What new hybrid thing might emerge?

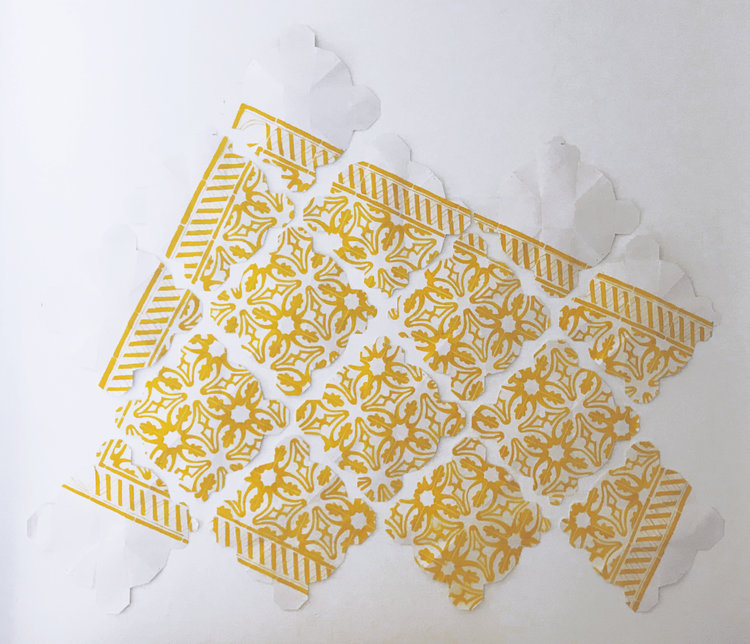

I ordered a sleeve of takeaway containers, pried off the metal handles, and laid several cartons flat. Using my arsenal of bamboo brushes, I painted a tile pattern from my Cuban apartment across them. I chose a rich yellow acrylic ink reminiscent of a shade called “wong” that was used only by Chinese emperors. This was also the surname given to my father when he immigrated to the United States in 1939 during the era of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

My grandfather had entered the States illegally, so he couldn’t bring his son. Instead, he turned to a friend who was Chinese but had American citizenship. His friend, a Mr. Wong, sent for my father from Guangzhou, claiming him as his own. My father became part of a generation of “paper sons,” and although he was reunited with my grandfather, in the transaction our family name, “Liu,” was erased. This color—this “wong”— references both a royal privilege that lasted through dynasties and a part of my family’s identity that became disposable.

Take Away

by Katarina Wong

(click for full-size images, titles, and captions)

I called my hybrid pieces the “Take Away” series. Sometimes I would scramble the tile pattern, as in “Take Away (Landscape),” which was inspired by misty Chinese scroll paintings, or I’d cut through the cartons, letting the negative space create the image.

Eventually, I wanted to translate these pieces into a medium similar to cement tiles. Porcelain was a natural choice. It is unexpectedly durable, and porcelains play a prominent role throughout Chinese art history. In “Take Away (Runner),” for example, I glazed the Cuban tile pattern purposefully askew across a grid of carton-shaped porcelain tiles, resembling a puzzle that is either coming together or falling apart.

My “Take Away” series ultimately was inspired by a longing for home—a physical one and one I carry in my heart—a way of merging what’s transitory with what endures. My father is no longer here, but my memories of him, stories from his childhood, his pride in his culture, are contained in every brushstroke. These pieces also hold my mother’s stories, my relationships with friends and family in Cuba, and the feeling of walking across the cool tiles in my Havana apartment—floors that stretch across time, back to the building’s beginning in 1928, to the present, and then into the future, where I hope more generations will play, grow, love, and create on them.

About the Maker

I’m an artist and writer based in New York City. Through my arts practice, I merge disparate aspects of my Cuban, Chinese, and American cultures. As a first-generation American, I’ve never felt fully claimed by any of these cultures, and my work is a way of reconciliation and reclamation. I use a variety of media, including installation, drawing, painting, and porcelain, and create work that merges iconography and meaning from my diverse cultures. My artwork has been shown nationally and internationally, including at the Art Museum of the Americas in Washington, D.C.; the Chinese American Museum and California African Art Museum, both in LA as part of the 2017 Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative; El Museo Del Barrio and The Bronx Museum, both in New York City; The Fowler Museum in LA; the Nobel Museum in Stockholm, Sweden; Fundacíon Canal in Madrid, Spain; and the Coral Gables Art Museum in Miami. I’ve received numerous grants and awards including the Cintas Fellowship for Cuban and Cuban-American artists and a Pollock-Krasner grant, as well as residencies at Skowhegan; Ucross Foundation; Ragdale Foundation; the Kunstlerhaus in Salzberg, Austria; and the Open Art Residency in Eretria, Greece. My work is in numerous private and public collections including the Scottsdale Museum of Art and the Frost Art Museum in Miami, FL. In addition to my visual arts practice, I write about immigration and Cuba issues, including Cuban artists, as well as professional development articles for artists. I’ve written for The New York Daily News, The Miami Herald, Entrepreneur, the Art Business Journal, and the Two Coats of Paint blogazine. My essay “Between the Lines: Messages from my Family in Cuba,” was included in the Bronx Memoir Anthology, Vol. 3 published in 2019. I am currently working on a memoir about my Cuban Chinese American heritages. I have an MFA from the University of Maryland, a Master of Theological Studies in Buddhism from the Harvard Divinity School, and a BA in Classics from St. John’s College, Annapolis, MD.

Photos courtesy Katarina Wong. Used by permission. All rights reserved.