Terrible Awful Beauty

by Angela Voras-HillsThe night Trump was elected, I lay in bed awake all night, wondering if a nuke would reach the Midwest. I was sure we would all explode before the night was over. Lots of people were afraid in different ways, but my fears always culminate in the explosion of the world. Have you seen the movie Melancholia? That is always where my mind ends up.

When I was pregnant, I was afraid of falling. I was afraid the baby wasn’t kicking. I went to the doctor a lot to be sure she was still alive. But then, she was born, and the fears were bigger. There was not a squishy waterball around her body to protect her if she fell. I was afraid if a knife was in the same room as her. I was afraid of stairs. I was afraid of sleeping and of not sleeping. Don’t get me started about crossing roads.

Two Months Before My Son Leaves for Belgium, We Visit the Zoo

And a few months before that, the airport is bombed. I get message

message message: am I letting him go? And maybe I’m to blame,

because I never told them I’d once caught him running on the roof

of our third-floor, that he was once hit so hard by a car his shoes

flew from his feet into air (a story I heard as his friends joked

about the lady who’d hit him, who’d cried and hugged him in the road,

making sure he was ok), or when, just three days before the bombing,

a high school kid scrawled plans to shoot everyone on a bathroom stall.

And so, two months before my son boards a plane to Belgium, we feed

giraffes, and he poses with peacocks. He wants to see reptiles and primates,

his sister wants elephants, crocodiles, never stops running until she sees a baby

kangaroo—we all stop and watch him hop around his mother

who lays on the concrete floor, bored. He cleans her ears, jumps

on her head to engage her in play, and she swats him away. He is already

half her size, but clearly still a baby. He doesn’t give up until finally

she stands, and I say I think he’ll climb into her pouch! My son doesn’t

believe the joey will fit, and I tell him he will fit, and then, an illusion—

the pouch one minute tucked against the kangaroo’s belly, stretches,

touches the ground as the joey climbs in head-first, shuffles and turns

settling in. After that, there is little to see. Black paws peek from the belly.

The mother nibbles her fingers, drags her baby toward a food bowl, and I

follow her eyes down the dark corridor toward the metal door bursting

open, the light blasting in, my daughter running out into it.

When I spend a lot of time at Target (or, more recently, internet shopping), I write nothing. I let all of my anxieties be swept away by faux eucalyptus wreaths, bamboo potato bins, vetiver candles— the promise of an organized home, manageable children, an “Instagram-worthy” life. But when I get these things home, I am unsatisfied. Most things I buy, I return within a week.

Haunted

Living alone, I’d call my mom, make her listen

as I moved room-to-room

looking in closets, behind doors,

under the bed, anywhere

a man could fit. I plugged my curling iron in

each day before showering, imagined

identifying a man in a lineup

by his melted cheek,

his missing eye. By then, I’d seen enough

Law & Order reruns to play each scene

out until sentencing. Ever since

I was a kid, I’ve wanted things

to be fair, believed hand-on-my-heart

in liberty and justice for all, but I’ve also

been so afraid. Mostly of a death

I’d have to live through—

drowning, fire, kidnapping that ends with me

tied up in a hole filling with dirt.

My daughter is scared of ghosts,

believes they’re in each

corner of her dark room. I tell her

they’re not real, but once playing Ouija

at the cabin with cousins,

we contacted The Blue Ghost

and the light above us flickered blue/

burnt out, left us in dark woods alone.

So who’s to say? I’ve never walked

through a haunted house,

staged or otherwise, but my cousin

pissed her pants inside one, left

a puddle someone had to clean.

One year, the gun club

sponsored a haunted hayride, and I rode

through the forest, hay splintering

my ass through jeans, and when

a man jumped out of the dark

with a chainsaw buzzing at us, I thought,

“God, who knows if this is really

part of it? Who gets paid

to behave this way?”

This was years before a man

shot into a crowded concert

from a hotel window in Vegas

and before so many

defended his rights. I watch TV,

try to believe “these stories are fictional

and do not depict any actual

person or event.” My daughter

asks about monsters, and I say they’re not

real, but news breaks, and she knows

I’m lying. If ghosts are real,

what do they expect

from a four-year-old? By now,

you’d think we’d all have heard

the unsettled dead. You’d think

something would’ve changed.

It took me a while to recognize this cycle of consumerism and fear, and especially how it is encouraged among women, particularly mothers, and it is fed by social media. The amount of money a mom can spend on “baby gear,” and the sheer volume of stuff one can buy for a tiny human being who can only roll over, is a testament to this.

A few years ago, I watched the video The House in the Middle, which is a PSA made by the Civil Defense Department in the Fifties and sponsored by a paint company. The video suggests that if you (the housewife) keep your house clean (and well-painted), your family could survive a nuclear attack. Can you imagine? All you need to do is keep a clean house, and ta-da! Your family survived the nuke. From there, I read bomb-shelter shopping lists. I looked at fallout shelter meal plans. I looked at photo after photo of how mannequin families “survived” nuclear tests. All of these mannequins looked just like me. They looked like every mother I knew: cooking dinner, stocking the pantry, decorating the fallout shelter with new bedding, encouraged to buy things and stay busy.

The Mannequin Refreshes the Facebook Mom Group While Sitting on the Toilet

A pregnant woman has been reading— childbirth

sounds awful, bringing baby home is terrifying,

she wants someone to tell her it’s not. Someone

say it’s beautiful. And they do. 97 comments

gushing about the beauty, assuring her yes, it’s hard,

but you will only remember the joy of those first days,

they go so fast. The mannequin has had enough

babies to mostly remember the awful, the weight

of body after body escaping her own, she can barely

read the comments without feeling cheated

out of forgetting, so she scrolls past them, another

mom wants recommendations for a nutritionist,

her husband won’t let their toddler eat sugar, natural

or otherwise, and her toddler is losing so much weight

so fast now that he’s weaning, and that’s as far

as the mannequin gets before the door bursts open,

and a photo appears in her Facebook feed, and it’s

her baby a year ago, and here’s her baby today, and

she sees he was beautiful—the baby on the duvet,

stretching in his new skin, now wobbling in

on chubby legs, such terrible, awful beauty.

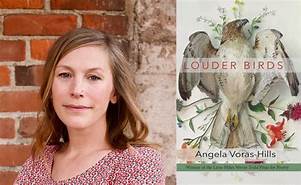

Poet, community organizer, and instructor Angela Voras-Hills grew up in Wisconsin. She earned an MFA from the University of Massachusetts Boston. She is the author of the poetry collection Louder Birds (2020), selected by Traci Brimhall for the Lena-Miles Wever Todd Prize.

Voras-Hills has received grants from the Sustainable Arts Foundation and Key West Literary Seminar as well as a fellowship from the Writers’ Room of Boston. She cofounded The Watershed: A Place for Writers, a literary arts organization, which evolved into Arts + Literature Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin. She lives with her family in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.