Speech and Debate

Halfway through sixth grade, my family moved from Roselle, a diverse working-class neighborhood, to Freehold, New Jersey, an upper-middle class predominantly white living. Thus began the year of silence.

Out of protest, sadness, depression, and puberty I vowed to my parents that I would never ever speak to them again. I later apologized for it, as it was said out of frustration more than anything, but the behavior remained. I wouldn’t speak over a certain volume. I wouldn’t make eye contact when I spoke. I wouldn’t speak unless addressed. My teachers called it selective mutism; my parents called it stubborn; and now they call it ironic. I didn’t have the words to call it anything. I didn’t know that I’d never be more grateful. If Roselle stayed home, I would have never found speech.

Five years later, high school theatre didn’t work out so I followed my best friend to the speech and debate room for the first meeting of the year. According to Mr. Drummond, my first ever coach, there were three fundamental tracks to the art of speech: limited preparation (LP), public address (PA), & interpretation events (IE). Limited preparation events deal with extemporaneous and impromptu speaking. Public address events deal with researching, writing, memorizing and performing informative, communicative, humorous, and persuasive speeches. Interpretation events deal with dramatic and humorous acting events. They showed all three at the Welcome Back Showcase. The president of the team performed a poetry interpretation program, and the power he exuded was enviable. Thirty people in one room stopped and listened in complete silence with full attention for ten minutes to one man. He held the entire room hostage. I had never seen that before. At fourteen years old, I thought, to be a part of a distinguished league of high school speakers, leaders, and influencers (which included Josh Gad, Zac Efron, Oprah, Brad Pitt, Kal Penn, and even more) would have been an honor—one I wasn’t sure I deserved, so ninth grade was a silent year regardless.

I started to compete more regularly in forensics (also known as speech, debate, 4n6, often confused with football or dead bodies) in the tenth grade, doing humorous interpretation and improvisational acting. Improvisational acting was the event that made me. Improv taught me everything about interpretation, everything about acting, everything about self-determination, everything about speaking as a cognitive process and everything about heart. The first time I finaled at a tournament I brought home a tiny fifth-place motorcycle trophy for something I never thought I could do, which was make people laugh with the sound of my voice, and I cried.

Soft voices never really harden, they just get heard.

I got serious about speech after that. I spent hours in the library reading books, suggesting them to all of the novices who had trouble finding literature to perform for competition. The next year, I took on the challenge of teaching the novices the rules and conventions of speech, which meant I had to learn them. Begging my parents to attend the George Mason Institute of Forensics (GMIF), a summer camp for speech kids taught by collegiate performers, definitely turned the tide. I studied and watched the final rounds of the National Tournament every year in someone’s New Jersey basement. Me and my friends who also were serious studied elocution, differing philosophies of acting, the principles of minstrelsy & oratorical education. We held house practices in people’s basements. We practiced monologues over and over for each other, recorded them for ourselves and played them back. We choreographed ourselves. We recorded ourselves. We read each and every ballot after each tournament in a McDonald’s booth. I bought two obnoxiously bright green speech suits and wore them with pride. I read literature, considered the themes I wanted to pick out of the author’s words and what method of interpretation I could take every week. Something that would effectively break walls but not make too many waves. I spent countless nights memorizing and perfecting and trying to get better.

One day, my voice just crystallized in front of me and I realized that the silence was over. No one could ever get me to shut up now. Not even myself. Even if I wanted to. My coach once told me, if you want to be able to change the way you speak, you have to change the way you breathe. Well at point, I’d went from choking to gasping. That’s where the art comes in. The body’s oral system works hard for those ten minutes. The more you are able to control your nose, your mouth, your lungs, your brain…the more you are able to become an extension of yourself.

My first dramatic interpretation (DI) in speech was of the book Warriors Don’t Cry by Melba Pattillo Beals my senior year of high school. Performing the words of that piece allowed me to fall in love with prose again. Warriors Don’t Cry is a compilation of Beals’ high school diary, a sixteen-year-old girl who was part of the Little Rock Nine in Arkansas surrounding the civil rights fight for desegregation. It told the story of a girl trying to make it to seventeen. Approaching my senior year as one of the few Haitian-Americans in a predominantly white school and neighborhood, I was just trying to get to seventeen too. Beals spends pages and pages going through her tumultuous year in Little Rock, holding no parts of herself and the experiences of her classmates back. The themes of hopelessness and the titular advice got me through my senior year of high school. I only semifinaled at our district tournament, meaning I never qualified for high school nationals. But according to Melba, warriors didn’t cry. In the face of injustice, the warrior spirit is flexible. The strength to leave home, go to George Mason, and pursue collegiate forensics competitive success would have been lost on me without Melba. She allowed me to exist outside self.

It was the first time I had ever heard it from my own tongue and the love of prose overwhelms me still. And this love now consumes a community. I’ve met some of my closest friends in speech. People meet their soulmates in this activity. Watching someone bleed for you will always leave tiny scars. We, as a community, heal with constant love.

In 2017, me and my duo partner won the American Forensics Association National Individual Events Tournament in Duo Interpretation, performing a programmatic ten-minute piece about modern day lynching in America. We dedicated our performance to lynching victims around the country and the Memorial of Peace and Justice newly erected in Alabama dedicated to these victims as well. We worked hard to include all sorts of groups and accentuate the details of this performance out of respect for ourselves, the literature, and the activity. Using my voice to speak for groups I can adequately represent allows survivors of injustice to tell their stories and live on. Using my body as their vessel has been one of my greatest honors. Here is where I developed the ideology that we are all walking this Earth considering each other, and that the inside matters more than we will ever know but the outside matters because it protects what’s inside. We would not survive without shelter, and the body we inhabit is shelter. Identity is always grabbing at our bones. So we stand up when we can. I do believe that those who are truly and inherently neutral comply to the system and therefore aid systems of oppression. Along this vein, those who do speech are the ones consistently disrupting the status quo.

I’m currently a rising senior at George Mason University, majoring in Public Administration. There are a lot of reasons I love GMU but I can definitely say that I picked and attended my college for speech. Graduating high school, I knew hell was a place without speech. Hell was a world where that could get taken away in an instant. After I graduated high school, our coach and our program stepped down. After my sophomore year in college, our Assistant Director of Forensics stepped down too. This year, after the Director of Forensics for our team left, I don’t think our team knew how to breathe. We were already walking around with open wounds. I have been doing speech and debate for seven years. Seven years ago, I didn’t have something that I knew would never give up on me, ever, as long as I never gave up on it. Speech has been the greatest love of my life. I have never practiced unconditional love before. But after the year our team has had, speech was the world’s most beautiful rose, with dried blood on the thorns, accepting the community’s flaws as necessary evils. Out of love for my art, I have lost sleep, lost job opportunities, lost focus in school, lost money, lost people, and almost lost my mind.

The biggest nightmare about speech is that it is such a diverse and beautiful community full of gorgeous and talented people who spend their weekends laying at the feet of a panel of men. They bare their soul and ask for a fair rank and are given back sexism, racism, classism, and problematic rhetoric time and time again. Microaggressions within the community began to creep on me. Judges and coaches in our community have always held all the power. They are the ones who decide who advances and keeps speaking. They’re usually older, straight, white males. To appease speech traditionalists, droves of us have been made to wear pantyhose, heels, full makeup, forbidden to wear pantsuits, and made to alter our bodies in sometimes unhealthy ways. Coaches have told me to smile wider to appear likeable even at my breaking points. It has made me stretch parts of myself for the amusement of those in power. Some have belittled the stories of survivors, pitted traumas against each other, criticized appearance on ballots more times than I can count, said things that they would never say to anyone’s face about things they would never be able to understand. Being judged on how beautiful I can make struggle, how appealing I can make my suffering, how pretty I can make myself cry for the benefit of an audience whose integrity has shifted has made me question the art of competitive public speaking recently. Highlighting the voices of people who didn’t have this platform was the most rewarding thing, not the trophy. Speech has made me who I am today but I have to recognize the hurt it has caused me as a young black woman. As the next generation of competitors rolls onto a field of so much potential, we have no choice but to leave it better than when we found it.

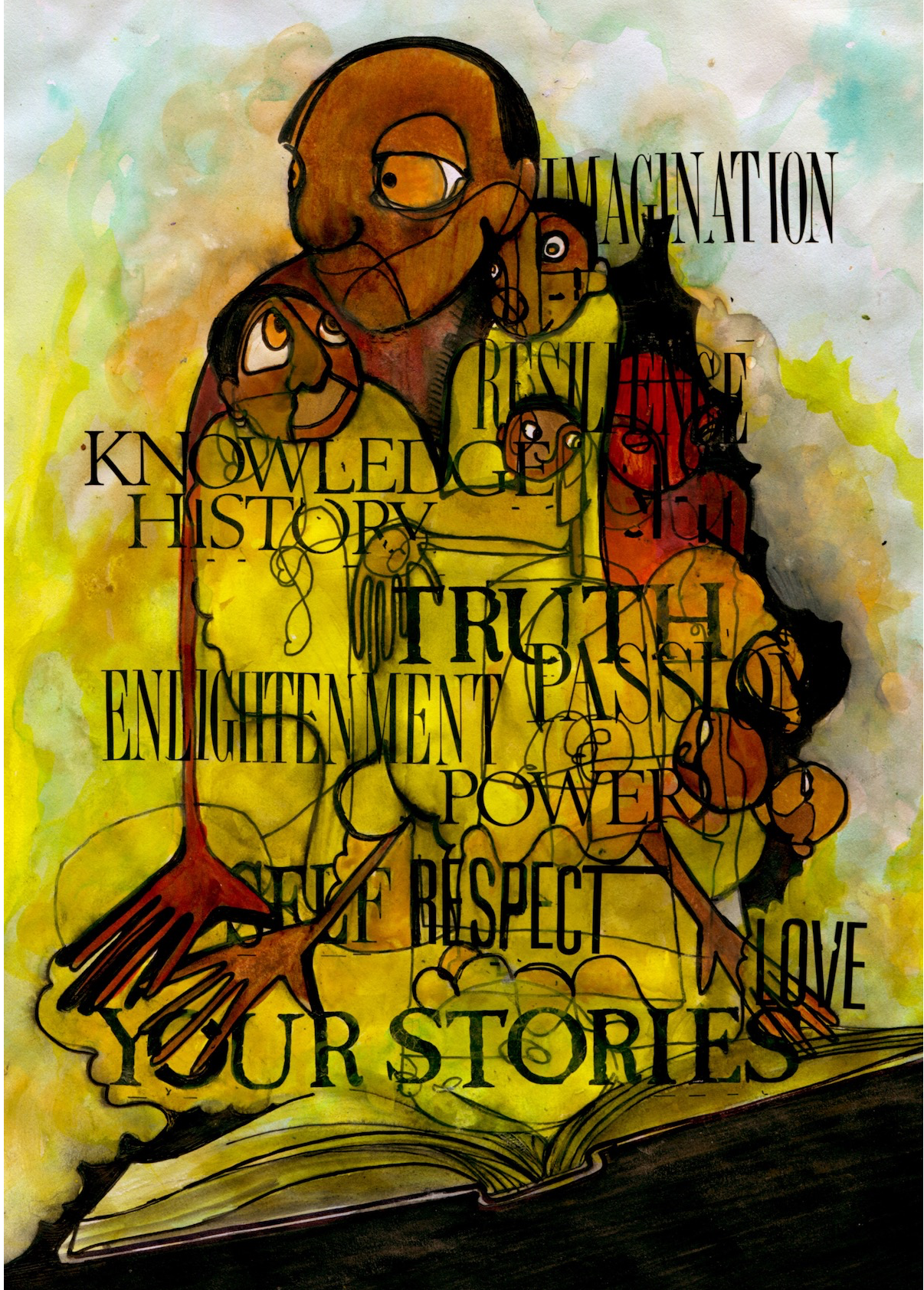

The speech community allows one to be able to participate in the facilitation of emerging action in this era. Entering a defining period of this world, the importance of voice has never been more compromised. Being part of something that bolsters an era of change, the words behind a revolutionary thing, has been integral to our heart. These messages deserve a home and an eternal story. Leaders, icons, competitors, coaches, and speakers like the ones I have gotten the privilege to compete against do the real dirty work under the grassroots in my head. Speech has provided a place for us as artists, creators, makers, and influences of great societal innovation. Language has always been a gift worth regifting. Every summer, working GMIF turns me into witness as young people grasp the power of voice and advocacy through words, their own and others, as a tool for social innovation and cultural change. The kids there keep something beyond themselves going and they haven’t even opened their mouths yet.

Time to start listening.

top photo courtesy Mernine Ameris

Recent Comments