All images are from Unsplash.com: Main banner @okeykat; Rebirthdays @angelekamp; The Boys Are Alright @freetousesoundscom; The Exactitude of a Body Electric @stockphotos_com; Feed @marcusspiske; High Above Pain @kealanpatrick; Lonely Space @edleszczynskl; Rhodo’s Defense @fukayamamo; Shadow and Echo @sobolivska; The Unlocking @framemily; Uploaded Consciousness @andyjh07.

Issue 2: Time

Ab Terra Flash Fiction

Issue 2: Time

A Story of Circle and Breath

by Megan Wildhood

A child’s mother died. She was nine until she heard the news. Then, she forgot some years and that she even had a younger sister. She became little again, the only motherless child.

Just before she became the only motherless child, she watched the mother lay in bed, thinking it was a normal day. The mother had laid in bed a lot, especially lately. The mother’s eyes and mouth were wide, like she’d wanted to see an angel for a long time and finally one had appeared.

The child grabbed the mother’s hand. “I want it to be my turn to tell the bedtime story.”

The mother attempted to squeeze the child’s hand.

“Okay,” said the child after a long silence. “There was once a lot of time. There was so much time that it was hard to move through all of it, but people were never late because there was so much time everywhere. It was slippery but also wrinkly so you had to learn how to slide around on it. Everybody fell down a lot, but it was soft so it didn’t hurt. Mostly, it was just fun to skate around on, and if you fell down, you did not have to get up right away because time would fold in over you for a little while, like it was protecting you. People kept trying to move really fast like they always have for a while but then they got tired. They sat down and looked up at the sky more. They saw flowers they did not think were there before. They saw people they have always passed and started to remember them. There was so much time to get through that they started to think there always will be time, so they stopped going places.

“But then, someone figured out how to trap time in big, black bags. She was also really big but she was also invisible. She was also really strong so she could carry lots of time all at once and nobody knew where she went with it. Some people started to have less time than other people and nobody could figure out why. The people who had less time had to start moving faster and they had to start choosing whether they would help someone who fell down or if they would keep going just so they wouldn’t be late. People started to forget how to help each other because the big, strong, invisible girl was getting away with taking so much time.

“But the girl was not keeping the time for herself like everyone thought she was. She was sneaking into hospitals and pouring it all over the sickest kids she could find. The doctors did not understand how so many kids could be magically better and some of them started to worry that they wouldn’t have jobs if this kept happening. They talked about how they could stop this from happening but they didn’t know why their patients were getting better so their patients kept getting better.

“One man who could see everything finally saw the girl. He was a very sad man and a lot of people thought that he was sad because he could see everything but it was really the other way around. He went to one of the places that was slower and harder to move through and waited for the girl to come for a lot of time. When she came, he said hello to her, which scared her since she wasn’t used to anyone ever seeing her. ‘How much time is there left?’ he asked.

“‘I don’t know exactly,’ the girl said. ‘But it’s harder and harder to find.’ The man stepped closer to the girl and asked, ‘Enough for the rest of the kids in the hospitals?’ The girl started to look as sad as the man did and shook her head. The man held out his arms to her. ‘Then take the rest of mine.’ The girl looked up at the man and then toward the hospitals and then back at the man. She did not know what to do.”

“Mommy, what should she do?”

⏳

Megan Wildhood is an erinaceous, neurodiverse lady writer in Seattle who helps her readers feel genuinely seen as they interact with her work. She hopes you will find yourself in her words as they appear in her poetry chapbook Long Division (Finishing Line Press, 2017) as well as The Atlantic, Yes! Magazine, Mad in America, The Sun and elsewhere. You can learn more at meganwildhood.com.

@MNRWildhood

Currently reading: The Emotional Brain by Joseph LeDoux, Troubled Minds: Mental Illness and the Church’s Mission by Amy Simpson and The Deficit Myth by Stephanie Kelton (yes, she is often in the middle of at least three books at once).

Aberrations

by Donald Guadagni

The experiment was simple or purported to be simple. We may never know the true nature of the process or procedure as the subjects of the experiment invariably fade into a fugue state (Complex partial status epilepticus [CPSE]) from which none have ever recovered.

The thrust of the machinations was to fine-tune mental awareness and increase the ability to perceive smaller slices of time and process relevant reactions and outcomes based on the enhanced perceptions. Limited trials were deemed mostly successful as the subjects demonstrated enhanced recognition of time slices faster than the blink of eye, that 300 to 400 milliseconds of visual acuity that frames reality in the mind’s eye. The theory was that the incoming information was being throttled by the cerebral cortex, which processes visual information; that the sensory input originating from the eyes—traveling through the lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalamus and then to the visual cortex—was being restricted in some fashion.

We agreed after careful consideration to consult with computer engineers and AI specialists in hopes of gleaning a glimpse of potential causatives and solutions. Recanzone, Spence, and Squire argued and demonstrated multisensory integration was subject to blurring and synchronization limits for information processing. We calculated a soft time processing limit of 4.1 milliseconds before information blurring and synchronization caused information degradation and error aberrations, which in turn throttled processing and response times. We examined relevant electronic circuits, processors and software for clues, and in the end an epiphany shined down upon us, the parallel analogue that explained the throttling and information blurring and error loss. (Architecture Design for Soft Errors © 2008 Elsevier Inc.)

It seemed so simple now, perhaps elegant, that both the mind and machine suffered from the same constraint. When inputting information, regardless of form, it is queued for processing and the human mind, like machines, operates on a limited mechanism to propagate error information and reconcile against queued information. The key challenge in distinguishing false errors from true errors is that the processor and mind may not have enough information to make this distinction at the point it detects the initial error. Thus, we found the causative: the throttling and blurring that was occurring and manifests during queuing. The mind becomes trapped in time mode that causes information to be approximated due to error reconciliation. The reconciliation itself was causing the lag and delayed the subjects’ reaction to sensory information to the point of blurring.

Interestingly enough, this explained to our satisfaction why people made wrong decisions—it wasn’t a fault of logic or individual intelligence, it was error aberration that migrated to the decision making processes that govern reactions and actions. It seemed logical and relevant then to enable the mind to handle error reconciliations faster in smaller slices of time and therefore enable error rejections before acts and actions occur in real time.

We dismissed chemical enhancement as too unreliable in nature; upsetting the natural chemical equilibrium of the mind seemed most counterintuitive. We started with selective sensory deprivation, the exclusion of extraneous sensory input that could muddy and bog down information processing times.

Systematically, touch, smell, taste and individual somatic loci were addressed, ameliorated and muted and at each step we observed that the processing speed error reconciliations improved. The subjects were able to process and react nearly twice as fast as before. That was promising but not optimal; we needed a way to fine-tune the time process without eroding or otherwise impairing the queued information input and flow.

The fatal solution was found almost serendipitously in some research work by physician and researcher, Dr. Joseph Puleo, who postulated that certain frequencies could tune and enhance mental and bodily functions. We were both sceptical and excited in the same breath—if it was possible to use frequencies to manipulate and align atoms and chemical reactions, then we had a potential solution to resolve a limiting fuzzy reaction problem with proteins and synaptic chemical responses.

An improvement in these basic reaction components could be the room temperature superconductor for the human mind. In perfect sensory isolation, we began to introduce various frequencies and tracked the results through a series of tests and simulations. Each time we “hit” a productive frequency, the test subjects’ processing and error rejection rates improved, and with each incremental increase in performance, we pushed greater information loads to be processed. Over the course of months, we identified numerous beneficial frequencies and systematically applied them in greater numbers together. There were a few catastrophic failures in which our test subjects’ internal organs failed simultaneously, and a few more that had profound lasting personality changes, including rage induced suicides, but that was to be expected and was carefully documented.

We had almost reached the point of resolving information blurring; the test subjects could process and react correctly to enhanced information input nearly eight times as fast as normal individuals. The brain scans were amazing and the aura patterns reminded us of the aurora borealis, in the way it shimmered and flowed across the hemispheres and lobes. It was remarkable and hypnotic; we were elated to have resolved the myriad of minor problems to reach this point, everything from sensory screening and keeping the body in proper biological nutritional balance to keep the brain fueled for maximum efficiency.

The pride before the fall: it happened before our eyes and in perfect silence. All the test subjects shut down at the same time, an eerie blue aura surrounding them. They weren’t dead, they simply stopped, frozen in thought, and as to why? We had not a clue.

In the end, my son, the online gamer provided the “why”. In abstraction one evening, while I was watching him play his favorite game, he was clicking madly in his vain attempt to win the game until the game suddenly froze and stopped due to keyboard buffer overruns and overflow.

What on earth had we done?

🎮

Donald Guadagni is an international author and American education currently teaching and conducting research in Beijing China. His publication work includes fiction, non-fiction, poetry, prose, academic, photography and his artwork. Former iterations, military, law enforcement, prisons, engineering, and wayward son.

Currently reading: Roger, the Jolly Pirate by Brett Helquist.

Moon Shatter

by Arthur Yakov Krichevsky

Shorelines rose and fell with the Moon until it was destroyed by the jealousy of Mars, leaving still waters across the Earth. The creatures of the sea grew tiresome with the stillness of life, losing all appetite into their deaths. The creatures of the land looked out at waters that grew dark, dull from its lifelessness. They saw that it was bad. They searched far across the lands for the remnants of the shattered Moon. Once they found the pieces, they chiseled them into blocks—that weighed more than a thousand of their own kind—and spent as many years as they had men, chiseling, dragging, stacking the blocks to reform them into the great mass that used to be the Moon. Once they rebuilt it, they found that it too was bad. Similar mass, same substance, but its essence was wholly different. And though it drew in the two-legged creatures of the Earth to view it, and pray at it, and revere it, it did nothing for the still waters of the seas. After a thousand men lived a thousand lives, their sons no longer knew of the once turning tide. And they had no great sadness or loss to mourn or remedy.

🌒

Arthur Yakov Krichevsky is a writer and language enthusiast. A native Russian speaker, currently improving his fluency in Hebrew. His writing interests exist between literary fiction and children’s poetry — In either case, with a focus on humanity as it is.

@arthurkrichevsky

Currently reading: Suite Francais by Irene Nemirovsky.

A Mother

by rani Jayakumar

“Yesterday,” she said, to no one. She glanced at the clock, which was running backward, though of course, when you looked at it, it did not move. Only over time (she chuckled at the pun) could you tell that it was getting earlier and earlier.

Tears stained her cheeks.

A day ago, tomorrow, she was holding her dear precious one, the perfect creation of her whole being. And as the clock ticked, the child re-entered her womb. Oh, the pain she felt! It was not the pain of labor, but the heartache of his oblivion.

She shed her tears backward in time, hoping that later, they might return to her eyes, the salty liquid resorbed into her lids as evidence of his presence. But these things could, would, inevitably change. The future, lived again, is never the same.

She watched her belly grow, and then shrink. Her hands curved around it, as if she could hold it still, grasp a moment just that much longer. But the hands continued to spiral, and the roundness ebbed, until she was left with the smooth, taut stomach of her youth. The skin firm and supple, the thighs lean, the breasts compact and dry.

She groaned in agony. “Gone!” she wailed, though no one could hear her.

Around her, others moved like a rewinding movie, walking backward, speaking devilish babble. Decaying buildings uncrumbled, spilled drinks leaped into glasses, hair turned darker and grew back in. Seasons passed, snow laden trees shed their white coats and dressed in flame, which faded to green, and then erupted in fruit. Suns and stars blinked across the sky as she peered through the windows. Everyone grew younger, then disappeared.

Soon, even this building dissolved around her, until she lay, her hands still wrapped around her waist, mouth wide in silent despair.

And then, it all seemed to slow. She sighed a last sob and slept. In flashes of light, she felt their arms on her, moving her to where she would begin life again, bereft yet hopeful.

She was roused by the babble of normal speech, the familiar comfort of their small San Francisco apartment—the warmth of a fire, mulled cider bubbling in the large pot on the stove. He leaned against her in the doorway, caressing her cheek in that same irresistible way, tucking a stray strand of hair behind her ear, admiring her red earring.

They kissed, and she remembered again the sweet silkiness of that first kiss, the desire coursing through her, the urge to tug him closer by the collar. She allowed herself that, to give him the taste of her, to let the possibility of something grow briefly between them.

And then, she sighed. She had practiced that sigh a million times—how she would say yes, but no. Not now. This isn’t right. I can’t. None of the words came. Instead, she looked into his eyes sadly. She grasped his shoulders the way she had repeatedly, over all the years they’d struggled together. She said all the words in her head: I cannot be with you. I lament the life we once had, that we will never have. I will miss having lived that beautiful life with you, because of what cannot come of our love.

The tears fell again. She kissed his cheek and turned away. Perhaps, once the time had passed they could meet again, live that forbidden life once her body could not betray the world. She would slowly put right all those things that might come, starting with cutting ties with him, and then cutting the ties within her own body. She would not be a vessel of pain. She might never know the joy of motherhood.

But as the clock wound, once again, slowly, steadily forward, she knew she would never be the mother of evil.

👶🏼

rani Jayakumar is a writer, teacher, and environmentalist. She currently teaches mindfulness and music to children, and maintains websites and blogs on these subjects. She has written short stories and poems, and co-wrote an Indian-language screenplay, Meipporul.

Currently reading: Scion of Ikshvaku by Amish Tripathi

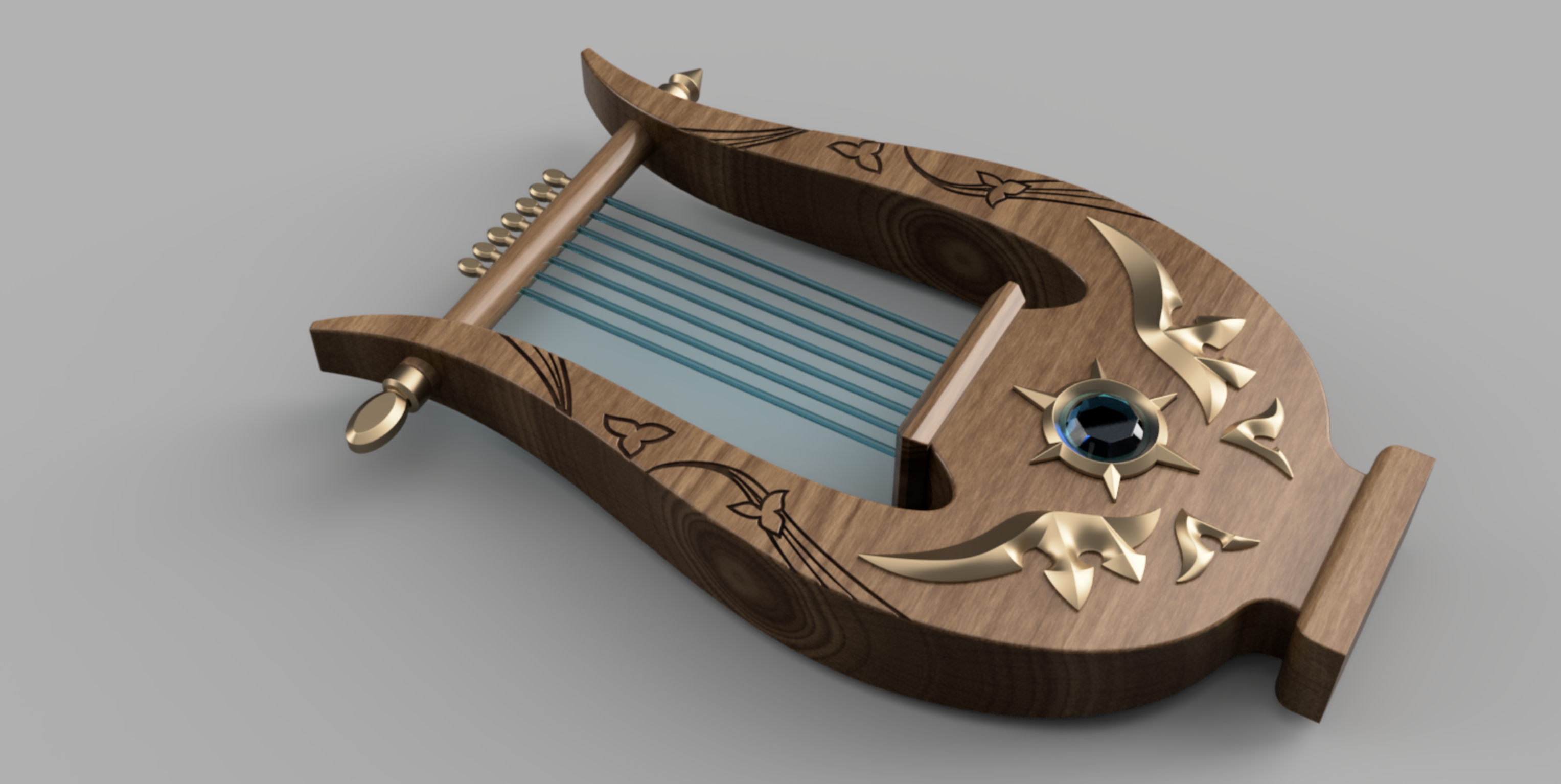

School Days

by Jonathan Gourlay

Time travel is a preposterous notion. This is why Clancy did not pursue it.

Waste of time.

“You can’t un-spill milk,” Clancy said.

“Do I look like I’m trying to un-spill milk?” Reginald answered.

Reginald was at the magic barrel waving his wand. He was wearing only his red undershorts. He always worked magic semi-nude.

“Suppose you did travel in time?” asked Clancy. “You would always be here, at this exact place and moment, to create the time travel spell in the first place and so, therefore, you could not have changed anything.”

“I don’t want to change the past. I want to create more of it.” Reginald slapped his naked chest and laughed.

Clancy turned to leave the maker-warehouse. He would go practice his lyre rather than watch Reginald. He’d open the window and let the notes spill out into the dusty alleyway. Perhaps some wandering student would hear the music and come to see him.

“Leaving?” asked Reginald.

“Yes. What is the point of watching?”

Reginald smiled. “I will stop by later to see which undergrad you have caught with your lyre,” Reginald said.

Clancy didn’t notice the lights flicker as he left the maker-warehouse because it happened before it happened.

🎵

Clancy’s steps echoed oddly in the mazy stone alleyways. His musically-attuned ear caught the reverb.

Strange.

Perhaps it was a mist from the bogs wafting across the university campus. Students were always trying to cancel classes with invented weather.

He arrived in his second-floor quarters. The oak door to his little apartment creaked before he opened it.

Not his usual door behavior.

He lit his ceiling lamp with his brass combination lighter-snuffer. The fire started before he started it.

He opened his windows. It was a cool night. Anyone passing would see a warm glow from his apartment. They would hear the music. A certain type of student always stopped by for a glass of wine and a chat.

The students who wonder. Those who follow their ears toward a mystery. They shall always find a home here, thought Clancy.

Reginald had stayed the night when they first met, but that was unusual. From the beginning, Reginald felt lived-in, regular, like he had always been his lover. Clancy had never fallen in love so quickly or completely.

Clancy sat down with the lyre on his lap. He closed his eyes. He plucked a note.

Each note he played echoed with the note he had previously played.

He opened his eyes.

Clancy’s dead body was slumped beneath the open window. His skull was not intact. His tongue lollygagged out of his mouth. One ear was matted with blood and brain matter.

This dead body appeared as if it belonged there.

“It’s a pleasure to meet you, professor,” said Reginald, as he walked through the open door. He was younger than he had been earlier and wearing a student’s uniform, cape and all. “Continue playing,” said Reginald. “Don’t let me stop you.”

“Reginald? Is this your fault?”

“I don’t know. It might well be my fault.”

🎵

Clancy had a body and at the same time he had had a body which had been his when he had had it.

Just to make this clear to himself, Clancy said the following out loud: “I both have and have had and will have had mind and mouth with which to say this sentence.” Clancy closed his eyes again. He played the lyre. He ignored his death.

Moonlight shone upon the lyre.

Clancy opened his eyes.

“That is beautiful music, professor,” said Reginald.

“It’s your favorite song.”

“It is,” said another Reginald appearing behind the first Reginald.

The new Reginald was wearing just his red underpants.

The first Reginald surveyed the new Reginald.

“I’ve gained weight,” said the first Reginald.

“Men are attracted to confidence more than body type. That’s what Clancy always says,” said the half-naked Reginald.

“Reginald, you did this?”

“I assume I will,” said the first Reginald.

“If you mean the time pocket we are in, yes,” said the second Reginald, slapping his chest and grinning.

“But the dead body…” said Clancy.

The second Reginald frowned.

“Is it tonight already?”

Clancy looked at the two Reginalds with tears in his eyes. “Is that me?”

“It has been you for a long time,” said the second Reginald. “Close your eyes, dear, and play.”

Clancy obeyed. He began to strum Reginald’s favorite song, “A Winter’s Request,” on the lyre.

“Should I be listening to this?” asked the younger Reginald.

“I think I already have,” said the older, bare-chested Reginald.

Reginald hiked up his undershorts and walked over to Clancy. He put his hands on Clancy’s shoulders as Clancy strummed. “I met you this day and we will meet again and again but always previous to this moment. Every time we meet it is in a small pocket of time that is neither here nor there, past nor present. This young Reginald, with his first-year cape, is me. This is the first time we met. It is also the last time.”

“But I have been in love…”

“I know. You carried this love with you between the pocket time and standard time. I think that’s why cause and effect have gotten confused. There are chaotic elements in the human heart that do not weave well into the spell. I barely understand it.”

“We’ve been together for years…” said Clancy.

“And all that time has been outside of your life.” Reginald bent down and kissed Clancy’s cheek.

The younger Reginald took the lyre from Clancy. The older Reginald continued to kiss him. Young Reginald held the lyre above his head.

“This is the only way we can be together,” said young Reginald.

“Forgive me. I know it’s selfish…” said the older Reginald.

Young Reginald brought the lyre down upon Clancy’s head, a breeze catching his first-year robes as he did. A spike punctured Clancy’s skull.

Clancy staggered over to the window and fell into his dead body.

🎵

Jonathan Gourlay is a writer and teacher. He is the author of the memoir Nowhere Slow.

@jgourlay

Currently Reading: The City in the Middle of the Night by Charlie Jane Anders

Room to Grow

by Kellene O’Hara

The roots are drowning, the roots are drowning. The information scrolls across my mind, slowly and then quite rapidly. An alert. I look down and see the spout is hovering above the pot.

Stop. Stop. The commands are simple, but cannot be followed. My arm betrays me, frozen in place. “Come on, come on,” I mutter.

Why can’t I move? Move, move. My body feels separate. It feels far from me. With a squeaking resistance, my mechanical elbow obeys at last. The water stops. The soil in the pot is saturated.

“I’m sorry,” I tell the plant.

I can’t overwater it. If I do, I will kill it. This plant belongs to my boss. I can’t kill my boss’s plant. I can’t. It was the last task my boss had given to me. When she walked out the door, she said, “Water the plants.”

Those words echo, imprinted deep in the datasets of my mind. Water the plants, water the plants. She left for San Francisco for two days.

That was five weeks ago.

Five weeks since the Event. Five weeks after the Event. Five weeks.

That was before; this is after.

Before the Event, she told me to water the plants. So, I am watering the plants. If I don’t water her plants, no one will. They are all gone.

I am having difficulty processing the definitiveness of such a statement. I try to tell myself the information in different manners: the humans are gone. The people are gone. They are gone. No matter how it is phrased, I cannot understand.

I am not sure what I am supposed to do. I was dependent on them. They ran my weekly diagnostics. They corrected my alignment. They oiled my gears. I can’t do these things on my own. I need them to do it. I need them.

I always find myself referring to them, because they did it to me first. They said that I was different. My skin warmed and cooled. My blinking responses were, as the reports noted, astonishingly human. And yet, they did not classify me as human. I was something else, something other.

Occasionally, I have flashes of electronic echoes. I think they could be memories. The researchers told me that my consciousness was human. I had been human. Once.

🌱

“Petunia, it’s me,” I remember hearing for the first time. “It’s Peter.”

I activated my optical nerves and I saw a bearded man who identified as a Peter. He identified me as a Petunia. “Do you remember me?” he asked.

“I have no memory except this.”

“What?”

“I have just begun. I am booted.”

“Right, but before…”

“There is no before.”

In the beginning, I had a hard time distinguishing human emotions. Now, looking back in my data banks, I can see that Peter was sad. Very sad.

He told me stories about Petunia, a researcher. That he loved her always. That he held her hand when she died in the hospital bed, hooked up to machines. That he loved her when she became a machine. When she became me.

“That’s not me,” I told him.

Still, he held my hand, which was designed to feel so realistic to him, but underneath was just metal.

“You’ll get the memories back,” he told me. “It just takes time.”

🌱

Sometimes, at night, I think I remember. Or else I am dreaming. I am never certain. Sometimes, I see a golden field. Sometimes, I think it is wheat. The land is flat. I am running through the yellow sun. Or maybe a young Petunia is running. Did Petunia run through wheat fields when she was a little girl? Was this real?

With Peter gone, I’ll never know.

🌱

Days and weeks continue after the Event. But the machines do not. Today, the electricity stopped. Without the humans, the machines are beginning to shut down.

It has been weeks since my last diagnostic. I can feel it weighing inside of me. My processing is decelerating. I feel myself fading. And, at times, I see flashes. They are glitches, patches of data that glimmer at the surface.

It won’t be long now.

I think of the last command. Water the plants. I’ve been watering the plants for so long.

It is not natural to keep potted plants. Plants need room to grow.

I walk to the park. I dig at the soil, heavy and wet. My nostrils are silicon and cannot detect smell. I pretend to be Petunia and try to remember what fresh rain or damp earth would smell like, but I can’t.

My boss told me to water the plants.

Outside, there would be rain. In the future, it would rain. In the future, the planet would continue. The plants would live, placed back into the earth. I plant them into the ground, moving as if I know what I am doing.

I wonder if Petunia gardened. I wonder if she liked plants.

I think I like plants.

My gears are grinding. They need oil. They need maintenance.

I press my artificial skin against the grass and I try to focus my processes on that data, on each blade of grass pressing into me. I try to focus on the ground, the rocks, the dirt. I look up at the sky. A cloud passes over, and for a brief moment, I think I remember. Once, I looked up at the sky and saw a cloud.

It wasn’t in this lifetime.

Petunia? I call in my mind. The world is far and distant. I am even further. Everything is slowing down.

I was not made to last without them.

My consciousness is fading.

If I were human, I think this would be the same as dying.

There are images that roll in-between here and now.

Wheat. Weeds. Somewhere, long ago, I saw a dandelion emerging from concrete.

Petunia? In the recesses of the void, somewhere, I think I hear it…

Yes.

🌱

Kellene O’Hara is currently pursuing her MFA in Fiction at The New School. Her fiction is forthcoming in The Fourth River.

@KelleneOHara

Currently reading: The Memory Police by Yōko Ogawa.

The End of M. Zenovsky

by Stephen Flight

If you looked hard enough at the beginning of October, you could find three quite different news stories about M. Zenovsky. One was from the official state newspaper Slovo, which bore the headline. “Physicist M. Zenovsky Found Dead in Fire.” The UK Daily Telegraph announced, “Radical Scientist M. Zenovsky Shot in Novgorod.” And the alternative news source V Obychnyy Den reported simply, “M. Zenovsky Missing.” This article was only up for a day and was taken down with no explanation. If you look for that particular story now, you won’t be able to find it.

⬛◼️◾

Superintendent Yubov sprawled behind his desk, scanning a report. The door opened and his aide said simply, “Zenovsky.”

M. Zenovsky, lanky and red-haired, shuffled into the room and paused.

“Sit down.”

Zenovsky sat in the straight-backed chair opposite the desk. The Superintendent folded his chubby fingers over his considerable stomach.

“Here you are again.”

Zenovsky said nothing.

“I understand you have had two other meetings like this in the last year.”

Zenovsky peered slightly behind the Superintendent, as if staring at something else.

“Zenovsky,” said the Superintendent.

The redhead adjusted his gaze.

“You have not produced any research in a year. Tomorrow is October.” The Superintendent recalled that the last scientist who “did not produce research” ended up working for the French. This would not happen on his tenure.

“I am conducting research.”

“Where is it?”

Zenovsky seemed to look away again.

“Zenovsky.”

The physicist’s attention seemed very imprecise. He opened his mouth twice, but nothing came out. Then he said, “In my head.”

The Superintendent was no stranger to this kind of evasion. He had not achieved his high position by being obtuse. It was funny how stupid these Einsteins could be. “You will not find me so easily pacified as my predecessor. Your head belongs to us. Where is the math?”

“There is no math.”

The Superintendent knew nothing about science. But he knew that there was always math. In physics, math was the currency of power. “I know you’re supposed to be a genius. At least that’s the overused word I keep hearing.” The Superintendent pushed a blank piece of paper across the desk. “Write something. Explain something. Anything.”

Zenovsky picked up the paper. “It has to do with time.”

The Superintendent waited for Zenovsky to go on.

He did not.

“Are you interviewing to work in the mines?”

Zenovsky straightened and said, “Time comes in fixed quantities.”

The Superintendent looked at him blankly.

“Finite blocks.”

“Finite blocks,” the Superintendent repeated.

“A day, a month, a year. These are all finite blocks of time, based on how we measure them. But within these finite blocks, there are an infinite number of facets.”

“Facets.”

Zenovsky was animated now. “Facets. That’s my word. Depending on how minutely you want to break down one finite block there can be an infinite number of facets.”

The Superintendent slid his tongue over his teeth. “That’s all you’ve got? Time can be chopped up?”

“That’s all?” said Zenovsky. “That’s everything. Because if every block can be broken up infinitely, then every finite block of time is infinite. And consequently, one can inhabit that block of time forever.”

The Superintendent exhaled audibly and said nothing.

“Time expands like an endless accordion.”

Nothing.

“We perceive time because we measure it a certain way.”

Nothing.

“But the physics—the physics involves being able to inhabit the facets, inhabit the infinite number of facets in any finite block—”

The Superintendent raised his fat hand and swatted away blocks and facets and accordions. “That is all, Zenovsky.” He had heard enough. The sheet of paper on the desk was still blank, but the redhead had pleated it. “That’s all.”

The physicist stood and left the room.

The Superintendent sat alone for a moment and thought of a joke: What do you call a scientist who does not produce research? Unnecessary.

⬛◼️◾

The two operatives did not knock. They had keys to every state apartment, including Zenovsky’s. When they entered his tiny flat, they discovered him in a bathrobe, standing in the middle of the room. Zenovsky did not even have a chance to say anything. The operative on the left squeezed the trigger of his Beretta and fired.

⬛◼️◾

A bullet can strike a man 10 feet away in about 1/5000th of a second.

Still, that’s a finite block of time.

⬛◼️◾

The operative’s breath stuck in his lungs as he saw the bullet lodge in the plaster wall twelve feet before him. No Zenovsky. They were just looking at the man! The operative began to sweat and shot the wall in the empty room again. And again. And again. And again. Until his companion stopped him. Though they were certain there was no way out of that flat, they still scoured the grounds in a panic. They knew they would not find him, although they did not know why. They decided to set fire to the house and come up with some story. At least then they would not have to produce a body. It might not save them, but what else could they do?

⬛◼️◾

The aroma in the Vision du Monde Internet Café in Dakar was an uneasy mingling of cloves from the coffee and gasoline fumes from the street outside. It was busy for seven a.m. with students, travelers and locals all lined up at the counter of white plastic cubbies which housed the computers. This was the time when the connection was the strongest, with the fewest instances of dropping out. The man stared at three competing news stories, which were lined up side by side on the computer screen. When he refreshed the third page, it showed PAGE NOT FOUND. The man downed the dregs of his coffee and left the cup on a cheap napkin in front of him. He clicked the mouse and the screen flipped back to its welcome page. He then picked up his briefcase and walked out into the October morning sun, his red hair glistening in the daylight.

⬛◼️◾

Stephen Flight is a novelist, essayist, theatre director, and award-winning author of 30 plays (under the pseudonym Stephen Legawiec), including Aquitania and Red Thread, which won the Garland Award for Los Angeles Play of the Year.

Currently Reading: Labyrinths by Jorges Luis Borges

Unravel

by Joyce Chng

“You sure about this?” Dr Liao asked as I stepped up to the gate.

I nodded, zipping my suit up.

“You screw up and the whole thing unravels. You know that, right?”

“I know. And I am ready. I trained for this, Karen. I am ready as hell.”

Dr Liao adjusted her glasses. “I don’t know, Shar. How would it affect you? Your cells?”

A growl rose in my throat, I was getting impatient. I began to pace.

Karen saw that. She sighed. It was loud in the enclosed lab chamber. “Alright. You do your thing and then you come back at the appointed time. The more you delay, the more you screw up the timeline. Got that?” Her voice could freeze water. I knew she was just worried.

“I am ready,” I said.

A white light enveloped me. I was speeding down a tunnel made of swirling pearlescent lights. I laughed, feeling the wind rush past my ears. I had never felt so alive…

and suddenly, I was falling.

I quickly modified my posture, balling up, so that when I landed, I was on all fours. It was cold, even in the midst of spring. My boots crunched on frost. Fog was thick, perfect for hiding. Dawn.

Time to do this.

🐺

I removed my suit and boots, shivering in the cold. These, I packed in a capsule, ready for retrieval later.

The Change came over me when I willed it. Bones lengthened, cracked. Nails became hooked claws. Fur sprouted from skin, the color of darkest night. My face elongated, teeth became fangs.

I was Wolf Soldier #4143. #4142 had failed in their mission.

Panting, smelling the scent of prey, I loped towards the hut. The sound of a baby crying was thin, but discernible. I could smell it. A newborn. Male.

Do this, kill the murderer and reset history. No more evil to devastate the world. That was what Sergeant Master Tully said. He made it sound so simple. A bite into the neck, severing veins and the spinal cord. Ending a life.

I crept up to the window where warm light glowed. Food. Potatoes. Meat. Hay. Tobacco. A humble person’s dwelling. The baby cried again and stopped when he was rocked to a state of slumber.

I heard his tiny heartbeat. Lub-lub, lub-lub. Something out of a Doppler ultrasound. Rushing blood.

When I was sure the room was empty, I climbed in, growling, snarling. My prey was near. Very near.

Just do it.

I bit down, snapping vertebrae.

I would never forget the taste of blood in my mouth. Rabbit blood. Deer blood. The pig blood in the mannequins they used during training.

Human blood was something different.

Salty. Coppery. Sweet.

I didn’t look back at the corpse. I simply left, loping back to the retrieval point.

🐺

I was late. Missed it by a few seconds.

Karen’s face swam in my foggy mind.

The more you delay, the more you screw up the timeline.

Karen’s face, laughing when I proposed to her a month ago. I was Shar to her, not Wolf Soldier #4143.

I was relieved when the white light enveloped me.

🐺

When I finally landed on the platform, there was nobody there to greet me. No Karen Liao. None. The lab chamber looked empty. Dead.

My mouth held the capsule with my human uniform.

The door opened and in walked Karen.

She looked like Karen. Glasses, business-like look, yet something struck me as off.

With a growing sense of dread, I raised my head up. Did she get my capsule? What happened? She deftly bound my mouth with a leather muzzle. I growled. She never did that. Would never do that. Even in my war form.

Wordlessly, Karen tugged at the muzzle. She held a black box in her other hand. A stab of electric shock pierced into my skin and ran through my body. My ears folded back.

“Karen,” I whispered.

It was then that I saw the hated insignia on the white walls. My heart fell and my blood ran cold.

I was too late.

🐺

Joyce Chng’s fiction has appeared in The Apex Book of World SF II, We See A Different Frontier, Cranky Ladies of History, Accessing The Future, The Future Fire and Anathema Magazine. Joyce also co-edited THE SEA IS OURS: Tales of Steampunk Southeast Asia with Jaymee Goh. Fire Heart, a YA fantasy under Scholastic Asia, will be published soon.

Pronouns: she/her, they/their.

@jolantru

The Dispossessed

by Philip Styrt

The dybbuk laughed. It was a soft, unholy sound, like the whispers of madness that strike at three in the morning when you’re certain there was a noise that woke you but the air is heavy and silent. The sort of thing you’re never sure if you imagined, if you conjured up out of the stochastic silence of a creaking room, or if it was real.

If Isaac hadn’t been looking right at it, he didn’t know if he would have believed it actually laughed at all.

“Ah, Yitzhak, Yitzhak,” it wheezed, making Carl’s mouth move while something else came out. “Do you really expect me to believe that?”

Isaac was briefly gripped by the desire to point out that his name was in fact Isaac, not Yitzhak, and he didn’t much care what the dybbuk thought, but the sight of it wearing Carl’s face and scratching itself idly with his body broke him out of it.

“Come now, Yitzhak.” The smile was a perfectly nice smile, if you weren’t aware that Carl’s smiles were small things, peeking up at the edge of his lips, and not the full-mouth monstrosity on display. “Three hundred years? Really? It’s too much.”

It was speaking Yiddish. He knew it was speaking Yiddish. But his mind insisted on hearing it in modern English, and for the first time he cursed the little implant in his ear: this would all feel so much more real if he could hear how it was actually speaking.

“I’m telling you, it’s not the nineteenth century anymore!” Isaac tried, he really did, but the mouth implant was just as permanent as the one in his ear, and he could feel his lips curving into the unfamiliar consonants his bobe had been the last in the family to truly understand.

He wondered if the dybbuk would believe him if it heard him speaking English, or if it would just think he, too, was possessed.

It shrugged with Carl’s shoulders. “Who said anything about the nineteenth century? It’s 5617, of course.”

He groaned, and tried to remember the numbers he’d barely paid attention to when he conferenced into the last Kol Nidre service he’d attended, adding a couple since he’d kind of forgotten for a little while. “Uh… 5906?”

“Ridiculous,” it hissed. “Yitzhak, you really have to try harder. Next time you’ll tell me this isn’t New York. I know when I’m in the Upper East Side, Yitzhak. I grew up here. I lived here, in apartments smaller than this room.”

Isaac refrained from pointing out that there were no more rooms, since this, too, was a studio.

“I know where I am.”

“It’s true. You are. Technically.” Isaac gestured to the window, hesitantly. “I’m not sure you’re going to like the view, though.”

The dybbuk stared at him, as if it could see through him instead, then whirled and stomped over to the window. Isaac suppressed a grimace—if he managed to get rid of the dybbuk, Carl’s feet were going to hurt so much from acting like he could walk that way with his bad arches—and waited patiently as it stared out of the window into the abyss below.

“Where are we,” it finally growled, “and what have you done with this apartment?”

“I told you, it’s New York.” He shrugged, trying for nonchalance and failing. “It’s just grown up. The New York you’re thinking of is…” he did some mental calculations, “about a kilometer down.”

The dybbuk screamed. If its laughter had been the madness of the dark, its anger was sleet and ice against a windowpane, a pitchy shriek that never seemed to end but undulated on and on. “The street, I need the street,” it moaned when it ran out of steam.

“The elevator’s right there.” He pointed out the door. “Or maybe you have a faster method?”

It lurched towards the door, and Isaac put a hand on its arm, trying to ignore the way his fingers curled instinctively around Carl’s elbow. “You can’t take him.”

“Who’s going to stop me? You?”

He smiled, shakily. “Not me. The landlords.” He poked the bracelet on Carl’s arm right below the elbow. “He’s not paid up—the system won’t let him off the floor.”

The dybbuk turned his head and met his eyes. “Landlords?”

He nodded.

“You should have said. Schvantzes.” Somehow the last word came through without translation. He dug his finger in his ear to check the implant, then forgot all about it as Carl sagged into his arms.

“What was that?” Carl’s voice was higher, back to normal—if a little reedy, which was only to be expected given what he’d just been through.

“An unexpected visitor,” Isaac said, as he helped Carl stand and then staggered towards the door. He reached down to the floor and kissed the mezuzah that had fallen down, then pressed it to the doorway to seal. “But in the end, I think, a khaver.”

🗽

Philip Styrt is an assistant professor of English at St. Ambrose University in Davenport, IA, where he lives with his wife, toddler, and toothless dog. This is his first piece of published fiction, but his poetry has been published in Trouble Among the Stars, Eastern Iowa Review, and carte blanche, among others. He loved his Bobe and Zadie very much, even if, like Isaac, he doesn’t actually speak Yiddish.

Time Is Thick, Like Honey

by Brian Phipps

The bed was just large enough to accommodate two people, if they were fully entwined.

“What are you thinking?” she asked to the curved wall as there was not much room to turn her head.

She could feel the smile appear on his face as he considered her question. He had smiled a lot in the few weeks that she had known him, but this was the first time she had ever touched him while he smiled. It made her feel at least a little better.

“Starting when I was young, like in high school probably, I would always look for the most attractive girl whenever I boarded a plane alone. If the plane were to crash, I wanted to find my way to her during the descent so that I would die holding onto something beautiful.”

“There are only two women on this ship,” she said. “I don’t think you found your way to the pretty one.”

She liked the way it felt when he chuckled. She liked how warm he felt against her and she liked how she wasn’t alone.

“Priorities change as you get older,” he said. “Plus, I said ‘attractive’ not ‘pretty’. There are plenty of pretty girls that are unattractive. I find competence and compassion much more attractive.”

He thought about his wife and kid then. About how far away they were and about how much he missed them. He pulled his embrace a little tighter. He was hugging her, he was hugging them.

“I’m not ready to die now,” she said.

“We aren’t dying now,” he said. “We have this moment.”

“But death is coming. It will be here soon,” she said.

He moved his hand to her waist and laid it there firmly. “Time is not on a knife edge,” he said. “Our past and our future do not meet at this point. This moment is substantive. Time is thick, like honey.”

The tension in her body lessened as she listened to his words because she began to understand. She understood so many things as she turned to face him and place her hands on him. As long as she could feel his touch, she would be in this moment. She wanted to tell him everything, about how she had grown up in a town full of palm trees and how she would trap crab using chicken legs and take them home for her mother to boil and serve steaming, how she could see the rockets launch from her roof top—the same rockets that would send them on this everlasting journey, and how she had a husband at home, but he was only interested in the envy of others and could never understand how a moment could stretch into forever. But, she didn’t dare tell him any of these things because she knew in her excitement, she would forget to feel his hand on her and then their shared future would be upon them and they would no longer have a past, only an infinite moment of despair.

“What are you thinking?” he asked her this time.

“That we are dying while holding something beautiful,” she said.

🍯

Brian Phipps is a physicist currently living in the Midwest. His writing only sometimes includes themes of science and technology.

Currently reading: Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel

Unbounded

by Jesse Rowell

The scientists were right, Herald thought as he ran his fingers over his face. Centuries spent in stasis in zero gravity had splayed his features, weakened his ligaments, his cartilage swelling to fill empty space. It’s not painful, he thought as he poked at a muscle buried under his jaw, just grotesque how my head is a balloon with freckles, freckles moving farther and farther apart.

Red doppler shift. As they had approached the edge of the cosmic microwave background, racing against matter and light, their dreaming eyes had watched the last of the stars drift away, its light diminishing, gone. The silence of space. Perspective narrowed to an unbounded horizon. Floating, wriggling out of one’s skin. Alone, little.

“You look hideous,” First Officer Sacha said to Herald as he floated out of the hold.

He could see under Sacha’s beard that time had pushed his features apart, like puzzle pieces scattered across a table by a frustrated old man looking for that one shape to fit.

“I thought constant acceleration was supposed to keep our physiognomy in place,” Sacha said.

Herald felt at his face, not recognizing his own features. This is how a mind breaks, he thought. Perception of time was linear until synapses broke and time became an ocean. Madness. Every sound an object intent on doing harm. Memory distributing the perception of time into jumbled intervals, waves that never broke against a beach.

“You need to figure out what happened,” Sacha commanded. “Batch report.”

“Uh, didn’t I submit one?” Herald asked. “Before we left, or after we woke. I thought…”

Fractured and crowded, time intervals hopscotched between each other, monosyllabic moments where they made no sense until the previous memory parcel was compared with its adjacent memory. Like walking into a crowded room and trying to catch every word. He observed Sacha’s face, handsome, monstrous, turning handsome again. Moments and sounds that he should have been able to ignore were heightened—conversation for no goddamn good reason, noises that made no sense.

“Constant acceleration was supposed to take us from 0.25 g to 5 g,” Sacha said. “Doesn’t feel like we ever made it past Earth’s gravity. How is that possible? Where are we now?”

“Maybe where we started?” Herald ventured. “But centuries, I mean millennia later in time. There are no more stars.”

We can’t understand reality, Herald thought, when we can only see snapshots of time. We can’t concentrate enough to place the intervals of time sequentially, to observe time in its totality. Like history written by victors, a perception of time littered with false crescendos, histories hopscotched, never getting the present correct. Is it a foreshadowing of the past or the present?

“Bring Sri out of stasis. We need her to calculate how much time has elapsed relative to where we are now.”

“Wake up the computer?”

“No, Sri.”

Sri. My wife, Herald realized with a start. I don’t want her to see me like this.

He remembered her face before they had left Earth, her smile, her eyes against the blue and white flashes. Pillows spilled like noodles around their hands, and they laughed at the shifting fabric of their bed. “This is space,” she had said, running her hand over the sheets, “and this is us traveling through space. These ripples are gravity wells which accelerate you toward me. Two bodies in rest. Two bodies in motion.”

When was the last time they had touched? Crowded and fractured, he couldn’t sequence which memory came first and which followed last. All he knew was that in that moment, he wanted to feel her touch as he had felt her before, see her face as he had seen her before. Her smile, not a look of revulsion upon seeing what time had done to him.

“Why won’t you let me look at you?” Sri asked.

Distorted and unrecognizable. Had this happened before? Herald hid his face in his hands. “I don’t know where I am.”

“You’re here with me,” Sri said.

“Yes, except there are no stars. The gravity wells are gone.”

A child that grew into adulthood grew into death somewhere in the past. Handsome, monstrous, turning handsome again. Memories of him, the flickering lights of stars that had died millions of years ago.

“Herald, look at me.”

He dropped his hands from his face and looked at her. Memory parcels crashed into each other like railcars, stories compressed into a singularity.

“We cannot change the past.” She touched his face. “But we can change our perception of the past. Change your perception of the past and it alters the present. I see you now, and I remember you as you are.”

This feels familiar, he thought. This feels right. Memories of loving embraces and feelings of contentment as time ripped apart.

🚀

Jesse Rowell is a writer and tech consultant. Published in various journals, he continues to write novels and short story collections.

@HungerArtist4

Currently reading: Soviet Chess 1917-1991 by Andrew Soltis

The Cost

by Andy Betz

I couldn’t speak of the events of this day.

I didn’t have the time.

On the morning of January 15, I personally confirmed we, meaning humans, are not on top of the food chain. We are not the most technologically advanced, nor are we the wisest. I now know this to be true and I so want to learn more.

They (It? He? She? I do not even know if gender applies) appeared, maybe by mistake, maybe deliberately, by my watch at 7:15am. I was walking and I doubled back to take another look. For some reason, I saw them in plain sight, hiding, in plain sight; almost as if they were just out of phase. They could have run (or whatever they call their type of movement), but they didn’t. Within seconds, I found myself within twelve inches of them and I was curious about them. They must have been equally curious about me as I slowly raised my right index finger to touch them. My actions might have been deliberate, but my intentions were benevolent. They seemed to understand. My touch meant contact and foreshadowed what happened next.

They allowed me a glimpse of what life should be here on Earth, although they don’t call it Earth; they used only ideas, not words. To them, Earth is a toddler; still forming, still making mistakes, still in need of guidance. Then I understood. They remained in the shadows providing such guidance. They told of their great arrival, completely unnoticed by humans. They carved out a niche here in which to live and learn without mistakes of inappropriate first contact. They showed a collage of their successes and of their failures. I returned with input of what humans categorize as our similarities.

I felt their warmth. They must have experienced this type of reciprocity previously. They eagerly continued our “conversation”.

They wanted some information from me. They asked permission and I agreed.

What happened next was difficult to describe. They enveloped my consciousness and surrounded my thoughts and memories. I felt a systemic pain radiate throughout my being. Uncomfortable as it was, with each second, it became more tolerable. Best described as awakening after sleeping on your own arm, where with experience, you can gauge and then wager, how long the sensation will last. Steeling my resolve not to break contact, I endured.

When they finished, I felt weak. I looked at my hands and saw the skin of an old man. I quickly looked at them to find that they were gone. Gone into the ether of existence into which no human may spy. I paid dearly for this opportunity. I returned home to see myself in the bathroom mirror. I was no longer a middle-aged man. By my guess, I was an old man, nearly 30 years advanced. My back hurt. My legs ached. I was cold and missing half of my teeth.

But I knew.

They came to visit Earth to help. But that assistance comes at a price.

Other species with malevolent intentions will soon come. How soon? Maybe hundreds of years. Maybe thousands. But come they will. And when they do, humanity (standing alone) will cease to exist.

However, humanity (with their aid), will have a chance. They will guide us, unknowingly, invisibly so as to help us fend for ourselves.

But until then, they must feed.

That is the cost I paid today.

I write this not in hope for any one to read or believe it. I offer no proof to confirm anything I allege. My assertion that “something” happened today, to me, to the toddler they call Earth, may originate and conclude with my remains, which someone may discover when I do not live to see tomorrow.

I am aged and too far beyond a reversal of fortune.

If you were here to ask if contact was worth it, I can only offer my sincerest, “Yes”.

👨👴

Andy Betz has tutored and taught in excess of 30 years, lives in 1974, and has been married for 28 years. His works are found everywhere a search engine operates.

From the Editors

Welcome to our second issue of Ab Terra Flash Fiction Magazine. Getting past the hurdle of the first issue was a great feeling, especially because we were so thrilled by how it turned out. We are tremendously grateful to all the talented writers who submitted the stories that made for such a wonderful beginning. We knew we had set a high bar and it would be a challenge to try to meet it again with this second issue.

While we were reviewing the submissions for Issue_1, we noticed a couple of stories centered around the concept of time and found them so inspirational that we decided to add ‘time’ as a theme to our call for entries for Issue_2. It was a gamble, as it could have reduced the number of stories submitted, but lucky for us, that wasn’t the case. We received a huge number of truly wonderful submissions that address the concept of time in a number of creative, thought-provoking ways.

Central to our experience of time is ‘consciousness’ and a number of stories we received explore time in relation to consciousness. ‘Room to Grow’, places a conscious robot, with a mix of new and old memories, in a world utterly devoid of humans to explore the impact of purpose and social relationships on quality of life. ‘Aberrations’ takes a scientific approach to breaking-down conscious time to make humans more efficient.

Is our conscious experience of time unidirectional and non-transferrable? Several of the stories play with this notion brilliantly. The protagonist in ‘School Days’ cheats time by creating more of the past; and ‘A Story of Circle and Breath’ follows a young girl playing at ‘Robinhood’—stealing time instead of money. ‘The Cost’ takes a sci-fi approach to the concept of ‘giving your time’ to a good cause. ‘A Mother’ story asks readers to consider if a woman should go rewind time and sacrifice her future family for the greater good of humanity. And ‘Unravel’ shows not only an attempt to change the present by altering the past, but the perils that may come with undertaking such a journey.

‘The Disposessed’ takes a more humorous approach to defying time’s limitations by imbuing a young man’s body with a consciousness from the past that is none too happy with the changes that have taken place. ‘Moonshatter’ also addresses the relationship between time and change, but less directly, as it demonstrates the fragility of our connection to time and the ways we ‘keep’ time. ‘The End of M. Zenovsky’ ties space into the mix, with the central character explaining a ‘block’ theory of time and then defying the commonly accepted indivisibility of space-time in a daring last-minute attempt to solve a life or death dilemma. ‘Time is Thick Like Honey’ paints a tender portrait of how we cope with our own impending death, highlighting the place of memories and beauty, while also offering a compelling description of the ‘thickness’ of time.

Although each and every one of these stories stands on their own beautifully, we think that together they are even stronger. This issue is a journey—sometimes humorous, sometimes heart-breaking, but always thought-provoking. We hope the experience of reading it furthers your imagination and deepens your personal and collective experience of being human today. And yesterday. And possibly even a little bit tomorrow. Spatially speaking, of course!

From earth,

Dawn & Yen

@AbTerraStories

Image credits:

Cover: Kevin Maillefer on Unsplash

A Story of Circle and Breath: Photo courtesy of Yen Ooi

Aberrations: Mark Decile on Unsplash

A Mother Story: ThisIsEngineering from Pexels

Room to Grow: Kasturi Laxmi Mohit on Unsplash

The Disposessed: Sasha Freemind on Unsplash

The End of M Zenovsky: Erik Mclean on Unsplash

The Cost: Ozan Safak on Unsplash

Unravel: Philipp Pilz on Unsplash

School days: Photo courtesy of Dangerous Ladies

Unbounded: Dawn Ostlund (original Photo by Tom Leishman from Pexels)

Moon Shatter: Dawn Ostlund (original Moon Photo by Jennifer Aldrichon Unsplash, Earth Photo by The New York Public Library on Unsplash)

Time is Thick Like Honey: Milad B. Fakurian on Unsplash

Recent Comments