It All Belongs to You: A Review of R. B. Simon’s The Good Truth

It All Belongs to You

A Review of R. B. Simon’s The Good TruthR. B. Simon’s The Good Truth (Finishing Line, 2021) ends with the poem “The Good Truth,” but good truths are scattered throughout the pages. In the landscape/philosophy/cosmology (pick your preferred term) of this collection, good truths are those things the poet learns—difficult things, often, but in the learning she looks closely and engages with people, histories personal and public, and the natural world. The poem “Indelible” ends with a final image of a tattoo come to life: “riding my night sighs to find you, / returning to me, bearing your wordless benedictions.” It is a poem about loss; in it, the poet writes about being a close witness to that loss, unable to save the person they cared about: “I kissed your spittle-flecked lips / between compressions— / come back to me.” The loved one’s loss remains: “I am so heavy with you.”

The language of the holy in the everyday recurs often. “Lightning” tells of “the wife of an ex / of an old friend of mine / . . . struck by lightning.” The woman is “lucky to survive” but terribly injured. As readers, we are asked to consider this particular injury, this awful aftermath: “the force of the blow / exploded her lower skull.” The first stanza begins with connection—how we know each other, how we would hear the news. The poem continues with how we are harmed, and how long it would take to heal, but it ends with questions unanswered:

What else does one do

when the very cells of your brain

have been shone through with sunlight?

When a fingertip of god

touches the soft tissue and reminds you:

you too, child, you too are mine?

Many of the poems refer to pain or trauma and what happens after. Several use the imagery of the natural world and its damage or destruction to talk about new growth. The poems weed and destroy; they talk back to thunderstorms, then quiet to listen. In “Prairie Fire” we learn about annual fires to root out invasive species and encourage regrowth. The Ho-Chunk practice kept the land healthy, and when white settlers came they brought disease and “larceny disguised as / gratitude,” and the prairie fires stopped. From this, the poem coalesces: “to destroy something so / very precious to you, / some part of what you call home, / is to let it return to you / filled only with / the essence of all / it was ever meant to be, / black and bare, / seeded / and ready for spring.”

The essence of Simon’s collection are the poems situated in childhood, and many of the poems speak of an unwelcoming place; she writes, “the entire planet is my homeland / but I claim no home.” “schools” tells of the casual racism and cruelty of children, compounded by the teachers’ inattention and shaming; in it, the child’s loneliness, her anger and her strength, are palpable. It’s also clear how common this occurrence was: the taunts, and the strategies she employed to get through each day. When “jolt—the shrill of the recess bell” interrupts the scene, and the reader feels a small relief, the stomach drops again when “a teacher awaits her, scowling. / you are always so slow! why don’t you exercise? she knows / she cannot win their games, but nods, and follows the current.” The poem utilizes a semi-regular long line, with copious quotations from speech and a third-person point of view. The effect is detailed, something like a fish-eye lens with all the focus on the girl on the swings, “opening her eyes to slits to find a way through.”

From there, the poems travel to a bar in Rosendale, Wisconsin: an Elvira pinball machine, Orange Nehi soda, and the men at the bar. The voice of the poem reassures us, “but always I stand / cocked, one-eyed, towards them / positioned just so / between the bar and / my younger cousins . . . always I note who is swaying, / who is slurring first.” Although still in the poems of childhood, this poem points to later poems where this speaker will become a protector, a lover, a mother, the person who cares for others, even as she’s navigating her own pain. These are parts of the good truth, too. Part of the message of those natural metaphors sprinkled throughout. The way creeping Charlie (the plant) is a way of talking about other invasive things, and loss in “Creeping Charlie (or, Late Summer, Post-Diagnosis, Pre-Hospice).” There, the poet wants to root things out but also “toss it all among the / compost, to spread among the irises / and grow you one more day.” As in “Indelible,” the ephemeral is made tangible, with ink and needle. Throughout R. B. Simon’s poems, there is this transmutation of experience—often painful experience—into ink and needle. These are the things that have happened and made me; written down, this is what they look like; consider metaphors of prairie fire, or lightning strike, or wind; but also—

—consider if instead of causing each other pain, we cared for each other. Those are the alternatives Simon offers in her poems. Instead of rejecting each other, instead of the violence of racism and hatred, instead of dangers of sway and slur and threat. “Traditions” recounts what the poet learned from her mother—both said and unsaid. In “Second Harvest” the poet addresses a child of the next generation. As with the collection’s opening poem, she notes the daughter is “lost in a rough country of ancestry,” but the second stanza begins: “I want to bring her baskets of our fruit . . . tart with her lineage, / sweet with the pith of who she will become, of / how she was rooted a thousand years ago.”

……………….And I am no master gardener

unskilled at pruning or coaxing bud to blossom,

…………..I can’t tell sly weed from straining sapling

………………………………except for this one

………………………………………..glorious shoot.

R.B. Simon is a queer artist and writer of African and European-American descent. She endeavors to create poetry centered in the mosaic of identity, the experiences that make us who we are in totality. Having battled mental health issues, substance use disorder, and trauma throughout her life, she is now in recovery and studying to become an Art Therapist, supporting others on the same journey. She has been published in multiple print and online journals including The Green Light Literary Journal, Blue Literary Journal, Electric Moon, and Literary Mama. The Good Truth is her first book. Ms. Simon is currently living in Madison, WI, with her partner, daughter, and four unruly little dogs.

C. Kubasta writes poetry, fiction, and hybrid forms. She lives, writes, & teaches in Wisconsin. Her most recent books include the poetry collection Of Covenants (Whitepoint Press) and the short story collection Abjectification (Apprentice House). Find her at ckubasta.com and follow her @CKubastathePoet.

The world made in these poems is stitched together by fragile associations—half made, tenuous. The language is incantatory, impressionistic. In “Preserving,” the form of the poem moves stanza by stanza with a word or image occasioning the next. The first, “I can spend a whole winter / in the summer of these lemons / if they’ve covered in enough salt,” leads to the next, where “Trucks are salting the roads / so I can drive . . .” An image of walking leads to an image of falling. Although this form is not as pronounced in other poems, overall the poems are made of these associations. Half-starts & skips. They are juxtapositions—a setting side by side of notions of the poet’s imagination (for better or worse). Sometimes, they offer a snapshot of worst-case scenarios or the kinds of ingrained knowledge that accumulate in small towns or rural areas of what could happen—because it’s happened before.

The world made in these poems is stitched together by fragile associations—half made, tenuous. The language is incantatory, impressionistic. In “Preserving,” the form of the poem moves stanza by stanza with a word or image occasioning the next. The first, “I can spend a whole winter / in the summer of these lemons / if they’ve covered in enough salt,” leads to the next, where “Trucks are salting the roads / so I can drive . . .” An image of walking leads to an image of falling. Although this form is not as pronounced in other poems, overall the poems are made of these associations. Half-starts & skips. They are juxtapositions—a setting side by side of notions of the poet’s imagination (for better or worse). Sometimes, they offer a snapshot of worst-case scenarios or the kinds of ingrained knowledge that accumulate in small towns or rural areas of what could happen—because it’s happened before. Silver Girl is told in sections: The Middle, The Beginning, The End, and Where Every Story Truly Begins. Through sections that skip between the protagonist’s college years, her late childhood, and immediately after college, the reader meets her family, her college best friend and roommate (and her family), and contrasts those dynamics. Sisters—their bonds and rivalries—are central to the story, both biological sisters and the kinds of sisterhood that develops when people live together, forced into intimacies by shared spaces and confidences. The protagonist sees college in Chicago as an escape from her Iowa town, from her family, but also as a chance to reinvent herself, to be someone else. At home in Iowa, she takes her younger sister Grace to the mall before Christmas, where she has to explain the bookstore isn’t a library and then beg the salesgirl for a book, pretending to be the family named on the paper ornament hung on the charity tree. All that work for a $2.25 paperback, but they needed every coin for the bus home.

Silver Girl is told in sections: The Middle, The Beginning, The End, and Where Every Story Truly Begins. Through sections that skip between the protagonist’s college years, her late childhood, and immediately after college, the reader meets her family, her college best friend and roommate (and her family), and contrasts those dynamics. Sisters—their bonds and rivalries—are central to the story, both biological sisters and the kinds of sisterhood that develops when people live together, forced into intimacies by shared spaces and confidences. The protagonist sees college in Chicago as an escape from her Iowa town, from her family, but also as a chance to reinvent herself, to be someone else. At home in Iowa, she takes her younger sister Grace to the mall before Christmas, where she has to explain the bookstore isn’t a library and then beg the salesgirl for a book, pretending to be the family named on the paper ornament hung on the charity tree. All that work for a $2.25 paperback, but they needed every coin for the bus home.

What I notice each time I re-read the book is how the poet’s voice and memories are bound up with her mother’s. Section One begins with her mother, “My mother lived on a moshav,” and tells how that came to be through the stories of the previous generation: an old British airport hangar, but before that a grandmother in a prison camp in Palestine, and before that both grandparents’ arrival by boat, and before that Romania. In the midst of these early pages, these primal stories, the poet tells us her mother’s first memory, “a dog barking behind a screened door, its mouth full of sharp teeth and drool, its legs taller than her three-year-old self.” Kopernik then makes the all-encompassing move, “her memory could have been any year, any country.” What child doesn’t have some terrifying memory lodged somewhere, what child doesn’t remember some beast at the door? It is the twining of these — these small anywhere-moments with the larger stories of families making and re-making, migrating & moving — that accomplishes the large and small of The Memory House. Two pages later, we are granted the title line, after more moments that refract the mother’s memories through the poet-daughter’s voice: “Our memories tangle into a single memory house.”

What I notice each time I re-read the book is how the poet’s voice and memories are bound up with her mother’s. Section One begins with her mother, “My mother lived on a moshav,” and tells how that came to be through the stories of the previous generation: an old British airport hangar, but before that a grandmother in a prison camp in Palestine, and before that both grandparents’ arrival by boat, and before that Romania. In the midst of these early pages, these primal stories, the poet tells us her mother’s first memory, “a dog barking behind a screened door, its mouth full of sharp teeth and drool, its legs taller than her three-year-old self.” Kopernik then makes the all-encompassing move, “her memory could have been any year, any country.” What child doesn’t have some terrifying memory lodged somewhere, what child doesn’t remember some beast at the door? It is the twining of these — these small anywhere-moments with the larger stories of families making and re-making, migrating & moving — that accomplishes the large and small of The Memory House. Two pages later, we are granted the title line, after more moments that refract the mother’s memories through the poet-daughter’s voice: “Our memories tangle into a single memory house.” Interspersed between these memory-moments are love poems, which seem to be about both finding one’s person as well as finding the self. The structure of moving between the early childhood poems and the adult poems make sense, as they suggest another kind of knowing and coming of age. The clarity of the language rings true: “I want this body / finally mine, naked, covered / in glitter and chicken feathers.” It is straightforward and defiant and joyful, tinged with the awful fantastic. Soon though, the beloved becomes a source of worry – long before the poem-story begins to hint at how the dissolution will happen, the speaker hints at meaningful differences between them; her girlfriend is a police officer, and the speaker wonders about her job, things she may have to do. “How will you see this world / with your gun? Is there anything / we can protect?” This too ties back to the childhood poems, when the poet tries to understand her father. In the poem “Inside Me” the reader sees the father, over and over again – in his chair, smoking, hauling rocks, always working. This poem is one of those that ranges across the page, with little breaks for breath, few guideposts of phrasing or punctuation. It ends with the resonant line: “there he is inside me singing what a surprise when I realize it’s not a song but a sob” – there’s no period. The poem ends, but it doesn’t end. The sob catches in the throat, nowhere to go.

Interspersed between these memory-moments are love poems, which seem to be about both finding one’s person as well as finding the self. The structure of moving between the early childhood poems and the adult poems make sense, as they suggest another kind of knowing and coming of age. The clarity of the language rings true: “I want this body / finally mine, naked, covered / in glitter and chicken feathers.” It is straightforward and defiant and joyful, tinged with the awful fantastic. Soon though, the beloved becomes a source of worry – long before the poem-story begins to hint at how the dissolution will happen, the speaker hints at meaningful differences between them; her girlfriend is a police officer, and the speaker wonders about her job, things she may have to do. “How will you see this world / with your gun? Is there anything / we can protect?” This too ties back to the childhood poems, when the poet tries to understand her father. In the poem “Inside Me” the reader sees the father, over and over again – in his chair, smoking, hauling rocks, always working. This poem is one of those that ranges across the page, with little breaks for breath, few guideposts of phrasing or punctuation. It ends with the resonant line: “there he is inside me singing what a surprise when I realize it’s not a song but a sob” – there’s no period. The poem ends, but it doesn’t end. The sob catches in the throat, nowhere to go. Tara Shea Burke is a queer poet and teacher from the Blue Ridge Mountains and Hampton Roads, Virginia. She’s a writing instructor, editor, creative coach, and yoga teacher who has taught and lived in Virginia, New Mexico, and Colorado. She believes in community building, encouragement, and practice-based living, writing, teaching, and art. She is the author of the poetry book Animal Like Any Other, from Finishing Line Press (2019). Find more about her work and

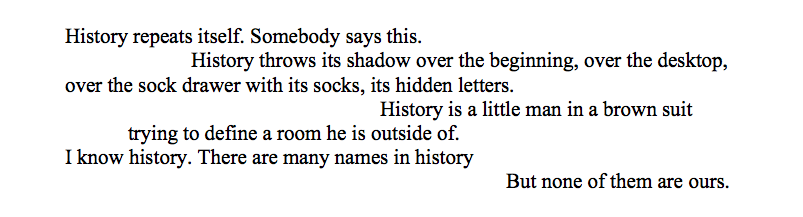

Tara Shea Burke is a queer poet and teacher from the Blue Ridge Mountains and Hampton Roads, Virginia. She’s a writing instructor, editor, creative coach, and yoga teacher who has taught and lived in Virginia, New Mexico, and Colorado. She believes in community building, encouragement, and practice-based living, writing, teaching, and art. She is the author of the poetry book Animal Like Any Other, from Finishing Line Press (2019). Find more about her work and  When, early in March, we began to spend most of our time apart—in our respective homes, in front of computer screens instead of people, texting and calling to connect virtually rather than face-to-face—I ordered novels and short story collections and poetry to feed the part of myself that missed friends, family, colleagues, and students. I tried to keep a schedule for the first few weeks, and it included live poetry readings in the quiet of my home, my dog attentive beside me. The books I lingered over, reading and re-reading, were poems that spoke of touch, vulnerability, bodies that comfort and confuse, pain that rises in words on the page and that, in a deft poet’s tongue, forces us to see the world in its trauma and longing. Those were Richard Siken’s first collection,

When, early in March, we began to spend most of our time apart—in our respective homes, in front of computer screens instead of people, texting and calling to connect virtually rather than face-to-face—I ordered novels and short story collections and poetry to feed the part of myself that missed friends, family, colleagues, and students. I tried to keep a schedule for the first few weeks, and it included live poetry readings in the quiet of my home, my dog attentive beside me. The books I lingered over, reading and re-reading, were poems that spoke of touch, vulnerability, bodies that comfort and confuse, pain that rises in words on the page and that, in a deft poet’s tongue, forces us to see the world in its trauma and longing. Those were Richard Siken’s first collection,

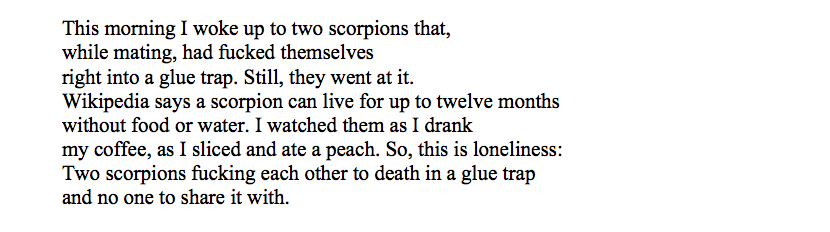

The anthology The Dead Animal Handbook, from University of Hell Press, takes a cue from this kind of poetry too, utilizing the imagery of animals—dead and gone—to foreground our humanity, or lack of it. In the introduction, editors Cam Awkward-Rich and sam sax write, “Rather than simply rejecting animality in order to claim humanity, many of these poems embrace the animal as a way of understanding the racialized, gendered, or sexual self, or in order to model forms of resistance.” Organized, in part, around the kinds of animal imagery in the poems (from birds, to fish, cats or dogs, or cattle), the included names are a wide selection of American poets—including important black and brown poets, and queer poets—as the editors put it, the “not straightwhitemen” of contemporary literature. Additionally, there’s a good mix of award-winning and well-known poets, alongside less-well-known poets—and since the collection came out in 2017, several contributors have become much more prominent.

The anthology The Dead Animal Handbook, from University of Hell Press, takes a cue from this kind of poetry too, utilizing the imagery of animals—dead and gone—to foreground our humanity, or lack of it. In the introduction, editors Cam Awkward-Rich and sam sax write, “Rather than simply rejecting animality in order to claim humanity, many of these poems embrace the animal as a way of understanding the racialized, gendered, or sexual self, or in order to model forms of resistance.” Organized, in part, around the kinds of animal imagery in the poems (from birds, to fish, cats or dogs, or cattle), the included names are a wide selection of American poets—including important black and brown poets, and queer poets—as the editors put it, the “not straightwhitemen” of contemporary literature. Additionally, there’s a good mix of award-winning and well-known poets, alongside less-well-known poets—and since the collection came out in 2017, several contributors have become much more prominent.

Because we’re all looking for the story that’ll save us, the poem to keep us alive.

Because we’re all looking for the story that’ll save us, the poem to keep us alive.

Recent Comments