Raki Kopernik’s book of prose poetry The Memory House covers a lot of territory — both literally and figuratively.

In four sections, the poet tells the story of three generations across three continents, contrasting kibbutz and urban life, communal living with single-family homes, dating, love and family dynamics. The poet’s voice inhabits grandparents, parents, and her own memories, with wishes for family and future. Throughout these particular and personal stories, there is a thread that opens up the individual story to make a wider, humanistic claim. It begins with the two-page preface to the book but has its clearest articulation on page 22. In the middle of narrating her family’s emigration to Israel, these lines: “Three quarters of a century later, in 2016, Syrian refugees on illegal boats, same, trying to escape into Europe. Same thing. Same.”

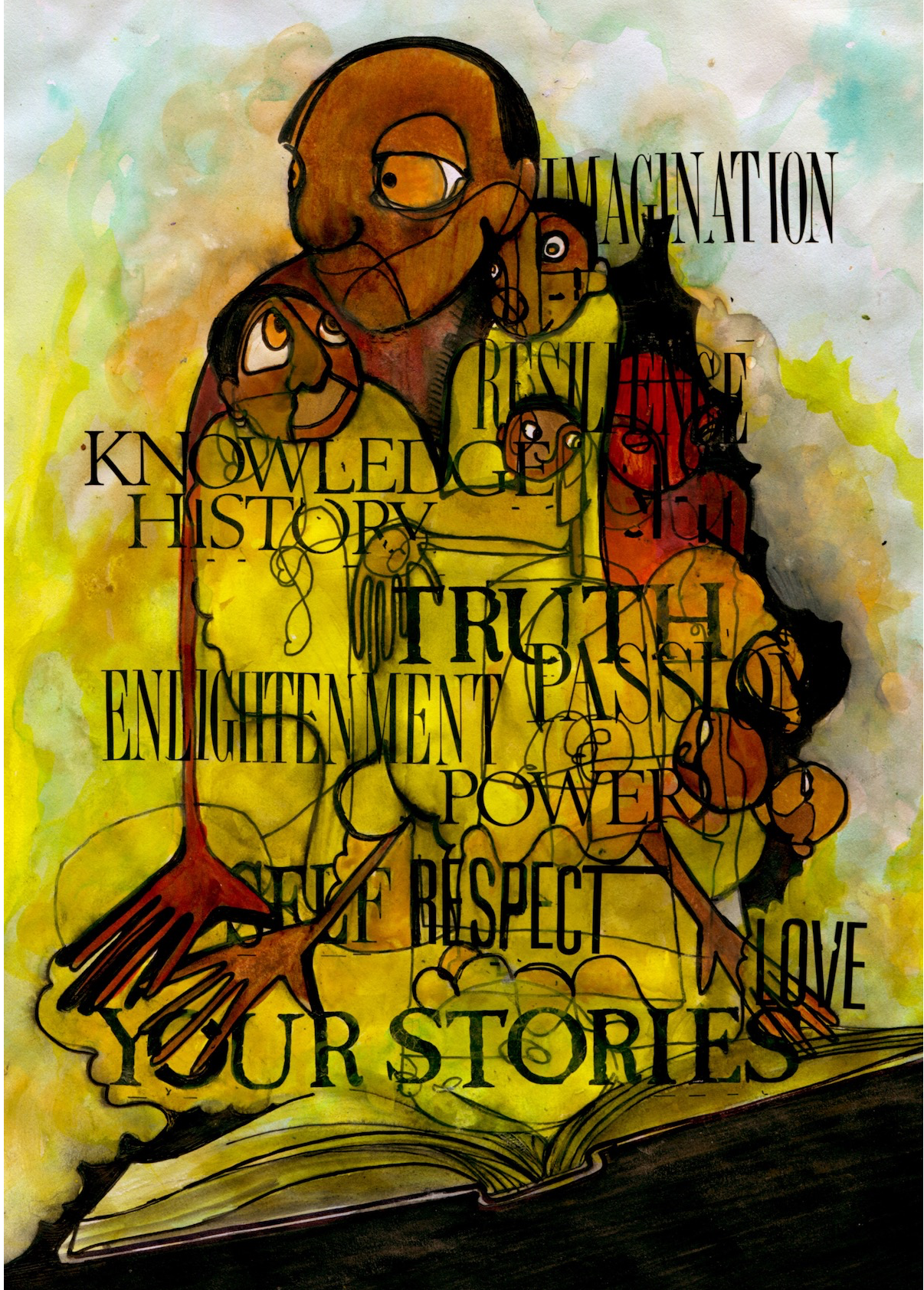

In the spirit of disclosure, I direct the press that published Kopernik’s book — we’re an embedded press at my university, and our students worked with the manuscript to learn editing, book layout, and the ins and outs of taking a manuscript to finished book. Our art students designed the cover (beautifully articulated ears of wheat) and created original artwork for the interior pages. Working with the students, they pointed out a number of things that inspired them about Kopernik’s book — how her forms invited them in, somewhere between storytelling and the poetry they were used to; how her long lines and details allowed them to picture the scenes she described, the fields of wheat and sunflowers, the groves of fruit trees; her sudden bursts of humor; the way food and taste threaded throughout every moment — cucumbers, butter, pears, and chocolate.

What I notice each time I re-read the book is how the poet’s voice and memories are bound up with her mother’s. Section One begins with her mother, “My mother lived on a moshav,” and tells how that came to be through the stories of the previous generation: an old British airport hangar, but before that a grandmother in a prison camp in Palestine, and before that both grandparents’ arrival by boat, and before that Romania. In the midst of these early pages, these primal stories, the poet tells us her mother’s first memory, “a dog barking behind a screened door, its mouth full of sharp teeth and drool, its legs taller than her three-year-old self.” Kopernik then makes the all-encompassing move, “her memory could have been any year, any country.” What child doesn’t have some terrifying memory lodged somewhere, what child doesn’t remember some beast at the door? It is the twining of these — these small anywhere-moments with the larger stories of families making and re-making, migrating & moving — that accomplishes the large and small of The Memory House. Two pages later, we are granted the title line, after more moments that refract the mother’s memories through the poet-daughter’s voice: “Our memories tangle into a single memory house.”

What I notice each time I re-read the book is how the poet’s voice and memories are bound up with her mother’s. Section One begins with her mother, “My mother lived on a moshav,” and tells how that came to be through the stories of the previous generation: an old British airport hangar, but before that a grandmother in a prison camp in Palestine, and before that both grandparents’ arrival by boat, and before that Romania. In the midst of these early pages, these primal stories, the poet tells us her mother’s first memory, “a dog barking behind a screened door, its mouth full of sharp teeth and drool, its legs taller than her three-year-old self.” Kopernik then makes the all-encompassing move, “her memory could have been any year, any country.” What child doesn’t have some terrifying memory lodged somewhere, what child doesn’t remember some beast at the door? It is the twining of these — these small anywhere-moments with the larger stories of families making and re-making, migrating & moving — that accomplishes the large and small of The Memory House. Two pages later, we are granted the title line, after more moments that refract the mother’s memories through the poet-daughter’s voice: “Our memories tangle into a single memory house.”

Because Kopernik’s book can be read as narrative or as a traditional poetry book, I don’t want to give away the ending — there are moments of resolution there, even if not in the mode of plot reveals. There are four sections overall: the first tells the story of the parents, growing up and meeting, emigrating to America; in the second, we encounter the poet herself, visiting Israel for summer vacations, staying back on the kibbutz with her maternal grandparents; the third tells the story of the paternal grandparents; in the last section, we find out the spare story of what happened when the parents arrived in America, how the poet’s family began.

In telling her mother’s story, Kopernik lingers on her mother’s dreams and desires — to stay on the kibbutz, to be surrounded by family, to begin a family of her own. When she falls in love with the man she will marry and start a family with, she resists him after he leaves for America. There are images of the mother-to-be, her care for her siblings, her developing instincts learned alongside the communal values of the kibbutz. She tells the story of her mother plucking a stinger from her brother’s face, giving him her precious squares of chocolate. She tells how the young woman pretended to mother her younger brother, seven years separating them. How she wanted four children. How even if she didn’t like the food served in the bet yeladim, she “knew not to complain about food.” In this inhabiting of her mother’s memories, Kopernik’s voice rises, moving up and up to survey not only her own family’s story but encompass the stories of others, to demonstrate one way to inhabit the past — through memory, through experience, through language.

In Section Two, when the poet visits her parents’ homeland, she writes:

Sometimes the Midwest smells like the Middle East in the heat of summer.

The smell of, nothing matters but this moment.

You might not think of the Middle East like that if you only know it from the news.

Experience has more dimensions than media. You don’t know the whole thing unless you can feel it on your skin, through the holes in your face.

But she’s told us all this before. We just didn’t have the stories yet — about Uncle Chocolate, who always brought chocolate. About the kibbutz pool, playing with the children, about the time a shallow dive left blood in the water. About how “puberty ruined everything.” About the rarity of pears — the sweetness of compote. In story after story, so many circling around meals, and food, and taste, there are the pleasures of sweetness — offered as gifts, made with love, created and cooked alongside family and the extended family created by the kibbutz. And there is the sweetness that is recognized because the thing offered is rare, or precious, not easy to find or keep — like the store called Kol Bo, which means “everything in it,” but the name is a misnomer. The daughter-poet, the American daughter-poet, points this out — her voice wry and laced with nostalgia.

The preface to the collection begins with a description of how there were no gardens, only dust, “the water sparse.” Prickly pears imported from Mexico, a fruit with “a tender heart at the barely visible center.” Kopernik makes the connection quickly, the heart of the cactus like Israel: “everyone wants the sweet middle. The core. What they think is the soul.” She names a literal place, she names an imagined place. She introduces a memory-place, peopled with loved ones and secondhand stories. Then she tells us, “borders are imaginary lines made up by people.”

Another theme, related to the insistence that Black women be strong, is the expectation for Black women to always be wholesome. Rooted in respectability politics, this expectation denies Black women agency in terms of how they present and express themselves. A later chapter comments on this theme when the ladies attend a burlesque show inspired by Magnifique Noir. Kayla, a Black female burlesque dancer, is slut shamed by a white woman for her sexually charged take on Magnifique Noir’s Cosmic Green. Even though their superhero identities are a secret, Magnifique Noir stands up for Kayla as civilians.

Another theme, related to the insistence that Black women be strong, is the expectation for Black women to always be wholesome. Rooted in respectability politics, this expectation denies Black women agency in terms of how they present and express themselves. A later chapter comments on this theme when the ladies attend a burlesque show inspired by Magnifique Noir. Kayla, a Black female burlesque dancer, is slut shamed by a white woman for her sexually charged take on Magnifique Noir’s Cosmic Green. Even though their superhero identities are a secret, Magnifique Noir stands up for Kayla as civilians.

What I notice each time I re-read the book is how the poet’s voice and memories are bound up with her mother’s. Section One begins with her mother, “My mother lived on a moshav,” and tells how that came to be through the stories of the previous generation: an old British airport hangar, but before that a grandmother in a prison camp in Palestine, and before that both grandparents’ arrival by boat, and before that Romania. In the midst of these early pages, these primal stories, the poet tells us her mother’s first memory, “a dog barking behind a screened door, its mouth full of sharp teeth and drool, its legs taller than her three-year-old self.” Kopernik then makes the all-encompassing move, “her memory could have been any year, any country.” What child doesn’t have some terrifying memory lodged somewhere, what child doesn’t remember some beast at the door? It is the twining of these — these small anywhere-moments with the larger stories of families making and re-making, migrating & moving — that accomplishes the large and small of The Memory House. Two pages later, we are granted the title line, after more moments that refract the mother’s memories through the poet-daughter’s voice: “Our memories tangle into a single memory house.”

What I notice each time I re-read the book is how the poet’s voice and memories are bound up with her mother’s. Section One begins with her mother, “My mother lived on a moshav,” and tells how that came to be through the stories of the previous generation: an old British airport hangar, but before that a grandmother in a prison camp in Palestine, and before that both grandparents’ arrival by boat, and before that Romania. In the midst of these early pages, these primal stories, the poet tells us her mother’s first memory, “a dog barking behind a screened door, its mouth full of sharp teeth and drool, its legs taller than her three-year-old self.” Kopernik then makes the all-encompassing move, “her memory could have been any year, any country.” What child doesn’t have some terrifying memory lodged somewhere, what child doesn’t remember some beast at the door? It is the twining of these — these small anywhere-moments with the larger stories of families making and re-making, migrating & moving — that accomplishes the large and small of The Memory House. Two pages later, we are granted the title line, after more moments that refract the mother’s memories through the poet-daughter’s voice: “Our memories tangle into a single memory house.”

Recent Comments