“Cinderella Is Dead” Offers an Engrossing Twist on the Classic Fairytale

"Cinderella Is Dead" Offers an Engrossing Twist on the Classic Fairytale

Two hundred years after Cinderella found her Prince Charming, the girls of the city of Lille in the kingdom of Mersailles are now required to attend an annual ball to find princes of their own.

Those who are not chosen or who refuse to attend face consequences, while those who do attend risk being paired with a husband who will mistreat them. In the midst of all this is Sophia, a sixteen-year-old girl who is in love with her best friend, Erin. When Sophia decides to flee the ball and hide in Cinderella’s mausoleum, she discovers that there is more to Cinderella’s story than she has been taught.

One of the most intriguing things about Cinderella Is Dead is the world-building. By setting the story in a post-Cinderella world, author Kailynn Bayron shows us the legacy of Cinderella’s story, her descendants, and those who were around her. Since Cinderella’s story is held up as an ideal, the women of Mersailles are expected to marry young in order to provide a better life for themselves and their families. Men aren’t bound to this and are heralded as princes and knights in shining armor regardless of how they act toward women. Those with rich families in positions of power can give their daughters an advantage at the annual ball that the less privileged don’t have. Not to mention, being straight is expected of both men and women.

One of the most intriguing things about Cinderella Is Dead is the world-building. By setting the story in a post-Cinderella world, author Kailynn Bayron shows us the legacy of Cinderella’s story, her descendants, and those who were around her. Since Cinderella’s story is held up as an ideal, the women of Mersailles are expected to marry young in order to provide a better life for themselves and their families. Men aren’t bound to this and are heralded as princes and knights in shining armor regardless of how they act toward women. Those with rich families in positions of power can give their daughters an advantage at the annual ball that the less privileged don’t have. Not to mention, being straight is expected of both men and women.

Yet next to no one notices how things are wrong in Mersailles. They see only the glamor of Cinderella’s story—or they are too afraid to fight those in positions of power. One bit of spoken dialogue goes something like, “By repeating a lie often enough, people believe it to be true.” Since Cinderella’s story is held up to be as sacred as religion, it is impossible for many to question it. In fact, the only people who end up questioning it are those who don’t fit the expectations of heteronormativity or submissiveness.

With a complex world comes a complex cast of characters—another strength of the book. It is particularly notable that nearly all of the characters are Black or mixed race Black, resulting in a narrative where race isn’t an issue. Almost all of the characters also have some degree of marginalization: protagonist Sophia is a lesbian, and secondary character Luke is gay but also, as a young man, someone who isn’t required to attend each ball. There are also characters who serve as a twist or extension of established characters, such as the prince, the fairy godmother, and the evil stepsister. Of the upended or legacy characters, the prince and the “evil” stepsister end up being the most interesting and creative.

Protagonist Sophia is someone who wants to make a change and fight social expectations but isn’t sure how to go about it. Due to living in a city with unrealistic expectations of women, Sophia is also unsure of her true potential. It doesn’t help that Sophia’s first love interest, Erin, is too scared to upend the rules of Lille to believe in or help Sophia. Thankfully, Sophia finds Constance, the last living descendant of Cinderella’s family, to help her form a plan to defeat King Manford. Constance is a little impulsive and brash, but she also is also a tender love interest and a thoughtful teacher. Constance telling Sophia some of the truth about Cinderella’s story and teaching Sophia how to use a dagger are some of the best scenes in this book.

The novel’s dialogue is another strong point that enhances its depiction of the characters’ emotions. One memorable conversation happens between Luke and Sophia when Luke dispassionately says, “People who don’t fit nicely into boxes the kings of Mersailles have defined are erased, as if our lives don’t matter. Have you ever heard of a man marrying another man? A woman being in love with another woman? Of people who find their hearts lie somewhere in the middle or neither?” To which Sophia bitterly replies, “Only as a cautionary tale.” This dialogue is reminiscent of how real queer people such as Oscar Wilde and Ma Rainey were criminalized for their orientation and sexual activities.

The budding romance between Sophia and Constance depicts how queerness is marginalized both in this novel and in real life, and it is endearing to read. Sophia initially admires Constance’s beauty and physical features and then begins to find it hard to concentrate or hold things whenever Constance touches her or is nearby. Meanwhile, Constance is keenly aware of Sophia’s budding feelings, and her initial flirting is amusing to watch. Sophia’s and Constance’s honest thoughts about their feelings about each other are especially sweet. I particularly liked when Sophia is admiring Constance and thinks, “Under the glinting moon, her hair is like a smoldering ember, her face so much like the splendor of the stars in the sky above us.”

All in all, Cinderella Is Dead is a dark, engrossing take on the Cinderella fairytale that challenges the reader to consider their role and the stories and history they have been taught to believe. It empowers queer women while also showing how queer and straight women can become a part of an oppressive system—and how men can become too entitled and privileged in this system, even as they are also marginalized. With a compelling cast of characters, magical dialogue, and creative twists, Cinderella Is Dead brings new life to a classic fairytale.

The Afro YA promotes black young adult authors and YA books with black characters, especially those that influence Pennington, an aspiring YA author who believes that black YA readers need diverse books, creators, and stories so that they don’t have to search for their experiences like she did.

Latonya Pennington is a poet and freelance pop culture critic. Their freelance work can also be found at PRIDE, Wear Your Voice magazine, and Black Sci-fi. As a poet, they have been published in Fiyah Lit magazine, Scribes of Nyota, and Argot magazine among others.

Top photo by Brian McGowan on Unsplash.

Raised by a strict, religious Christian father and separated from her alcohol-addicted mother, Ada wants to take her life into her own hands but isn’t sure how to go about it. Due to past trauma and her shaky upbringing, she is so focused on other people’s expectations of her that she hasn’t really considered what she wants for herself.

Raised by a strict, religious Christian father and separated from her alcohol-addicted mother, Ada wants to take her life into her own hands but isn’t sure how to go about it. Due to past trauma and her shaky upbringing, she is so focused on other people’s expectations of her that she hasn’t really considered what she wants for herself. Like most working poets, I struggle to find time to write. Scribbles on receipts, napkins, the marginalia on work notes, texts to myself, email drafts. The skeins of poetic fragments continued to pile up. In my upcoming book,

Like most working poets, I struggle to find time to write. Scribbles on receipts, napkins, the marginalia on work notes, texts to myself, email drafts. The skeins of poetic fragments continued to pile up. In my upcoming book,

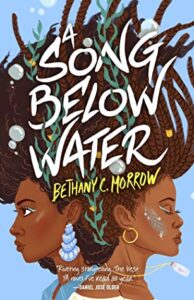

Tavia Phillips is a siren who must hide her powers in order to keep herself alive. Her best friend, Effie, is struggling with a painful past and strange happenings in the present. While they are trying to navigate their junior year of high school, a siren murder trial shakes Portland, Oregon, to the core. In the aftermath, Tavia and Effie must come together and come to terms with themselves.

Tavia Phillips is a siren who must hide her powers in order to keep herself alive. Her best friend, Effie, is struggling with a painful past and strange happenings in the present. While they are trying to navigate their junior year of high school, a siren murder trial shakes Portland, Oregon, to the core. In the aftermath, Tavia and Effie must come together and come to terms with themselves.

Recent Comments