The Portage

The Portage

by C. KubastaThe portage was boring, and a little intimidating, sometimes exciting. Depending on the trip, we had to gather things – the wetbags, paddles, whatever food, clothes, life jackets and cushions had collected in the bottom of the canoe – and carry them overland, following the canoes-with-legs through the trail, where the overgrown branches and weeds grabbed legs and arms.

This was the boring part. If the portage was long, and the straps started to slip from our shoulders, dragging, or the path was rocky, the portage involved some scrabbling, and this could be a little tricky. The intimidating, or exciting, part was at the beginning, when the grownups lofted the canoes up and onto their shoulders in one fluid movement (if all went well), and became the canoe-with-legs that led the way.

You portage between two bodies of water to keep paddling. You portage around a particularly difficult section of rapids, or ledges or waterfalls, if it’s not safe. You portage to connect. Portaging is the necessary overland travel for navigating waterways. The portage is the connection between the navigable waterways.

As a writer living and working in rural Wisconsin, metaphoric connections are often accomplished via methods other than the face-to-face interaction. I find myself seeking these connections more and more – needing to find a retreat or conference to be surrounded by “my people,” enjoying the breathing presence of other poets (even if just a handful) at a reading, finding a fabulous journal or magazine online, where the work featured speaks in a voice I recognize, as if I’ve found a very dear friend. Lately, I’ve been sending cold emails, where the subject line reads “fan girl,” to poets I love, and have been surprised how many have responded. With every new reply, I’ve let out a whoop. My partner asked, “Are all poets lonely?” And I replied, “No, we’re just nice.” But maybe we are a little lonely.

I’ve been lonely. I’ve been lonely in a room of writers where we seem interested only in talking about our own work, waiting for the breathing gaps in conversations to take up a thread, navigate back to our own interests, the lines we’ve laid down. I’ve been lonely in a room of writers who eschew any whiff of difficulty, any hint of work, who want the easy and accessible: the poem they already know. I’ve been in numerous conversations elsewhere where writers ask how I can possibly live where I live, if there’s anyone to talk to, whether there is anything to write about.

Wisconsin has a town named Portage: the fur traders called it “le portage” for the approximately two miles they traversed between the Wisconsin and Fox Rivers to cross the lower half of the state. Using this marshy patch of ground, the large Wisconsin, the upper and lower Fox, and Lake Winnebago, it was possible to cross the state and reach the bay of Green Bay, entering the waters of Lake Michigan. From Lake Michigan, all the other Great Lakes were reachable, and eventually the Atlantic. Although history books still speak of the French and British routes, the “discoveries” and place names left by these travelers, the routes they followed preexisted them, as did the knowledge they happened upon. Occasionally, the place names that remain catch us up with a strange and macabre poetry. Connected to the Fox River and Lake Winnebago near Oshkosh is Lake Butte des Morts – Hill of the Dead. In true Wisconsin fashion, we flatten and realign the pronunciation, obscuring both its semantic and linguistic roots.

I’m fascinated by the stories we’re told that may be wrong, but are all the more compelling for that. The so-called stories. Growing up, I was told that Winnebago meant “stinking water,” that Winneconne meant “hill of skulls.” Just now, I’m trying to find out whether any of that’s true. I remember the mantle of authority resting on adult shoulders when I was a child, the way they looked in flickering campfire light, the way they called out the names of birds, told of secret fishing spots, recalled the things told them by ancient uncles and fathers. There’s poetry plenty in the misremembered stories, the incandescent imaginings of childhood that will be undone by a too-bright light.

There’s magic at the end of the portage, when in another moment of grace, after one trip or more, all the paddles and PFD’s are piled at the put in, we are sweaty and swatting mosquitoes, and the canoes-with-legs change back into adults. The canoes, their aluminum bodies, land with a thud on the rocks and sand, the sometimes pink soil. We take up our spots. The stern is the paddler who steers. The front paddler calls out the rocks hiding beneath the surface of the ater. The duffer (usually me) is ballast, fitted between the gunnels, making sure the wetbags are securely fastened to the crosspieces in case we capsize, keeping our spare clothes dry, our bug spray and lunches and solitary roll of toilet paper safe until we get to wherever we are going.

Someday, we will portage. When we are grown, when we sit astride the seats, calling rocks, practicing our draws and pulls, our furious back paddles. We hope we are up to the job. That given a map with rapids marked, with campsites noted, we can navigate the days, safely shepherding the group along, shouldering the heavy load, heaving the aluminum or fiberglass canoe with grace and only a little grunting. So as Brain Mill continues to evolve and grow, with its Driftless Novella and Mineral Point Poetry Series (both named for the southwest corner of the state, from whence the Wisconsin also flows), and its publishers in Green Bay, we also begin the portage – to continue the journey and make connections with other small presses, writers, and poets in the Midwest.

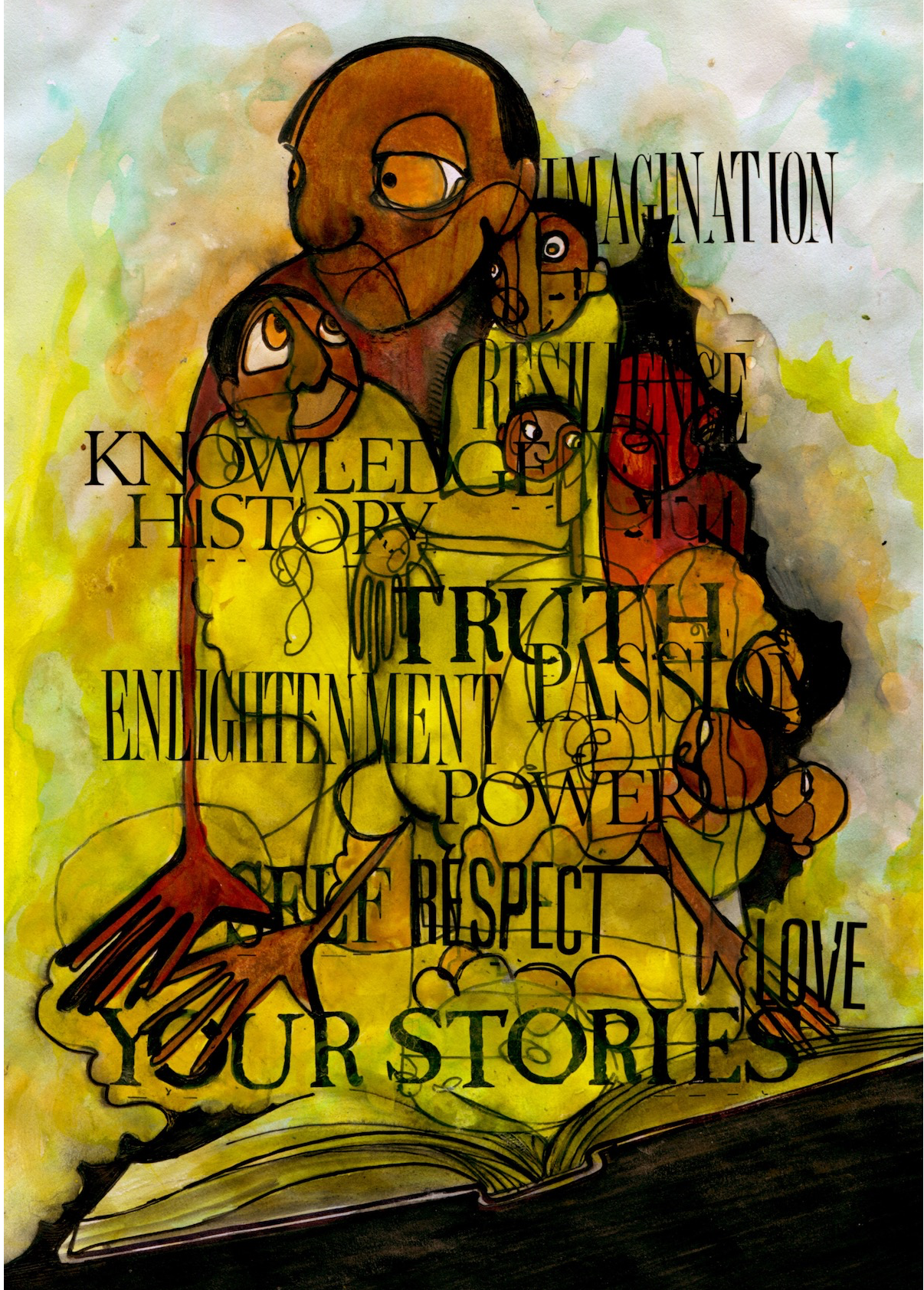

In keeping with Brain Mill’s mission, Portaging hopes to highlight marginalized voices, as well as marginalized forms – we’re interested in the experimental andthe hybrid. We also want to bring the work of small presses and art and writers’ collectives to a larger audience. We want to share some very Midwestern love, contributing to a community of literary citizenship in our own small way. Give us your raw and ragged, your genre-permeable, your visceral, your uncanny, your intentional and decidedly unbeautiful. If your work fits within this deeply shaded Venn diagram, please send a query through our contact form.

top photo by Chris Bair on Unsplash

Portaging celebrates new writing from the Midwest with a particular focus on experimental and hybrid work from small presses.

C. Kubasta writes poetry, fiction, and hybrid forms. She lives, writes, & teaches in Wisconsin. Her most recent books include the poetry collection Of Covenants (Whitepoint Press) and the short story collection Abjectification (Apprentice House). Find her at ckubasta.com and follow her @CKubastathePoet.

Recent Comments