“Tristan Strong Keeps Punching” Burns Bright and High

“Tristan Strong Keeps Punching" Burns Bright and High

While attending a family reunion in New Orleans, Tristan Strong is also doing his best to find his scattered friends from Alke who were brought into the real world. However, friends are not the only things that came from Alke.

When Tristan has an unexpected run-in with Alke’s oldest foe, King Cotton, Tristan pursues him and discovers a nefarious plot involving haints and departed spirits of the past. Now, Tristan must rally gods and heroes and new allies in the real world in order to defeat King Cotton once and for all.

One of the most notable things about Tristan Strong Keeps Punching is how it skillfully bridges the fictional world of Alke with the real world. Given that the folk heroes, gods, and other Alkeans now have their world literally stitched together with the real world, it is both fun and educational to see how they have been affected. This is especially notable because of the connections to the past and present that certain Alke characters and certain real-world inspired characters have. For example, there are the USCT, the United States Colored Troops, a group of soldiers who fought in the Civil War. The spirits of these soldiers not only serve as one of many guides to Tristan, they also have a surprising link to one of the Alkean folk heroes.

One of the most notable things about Tristan Strong Keeps Punching is how it skillfully bridges the fictional world of Alke with the real world. Given that the folk heroes, gods, and other Alkeans now have their world literally stitched together with the real world, it is both fun and educational to see how they have been affected. This is especially notable because of the connections to the past and present that certain Alke characters and certain real-world inspired characters have. For example, there are the USCT, the United States Colored Troops, a group of soldiers who fought in the Civil War. The spirits of these soldiers not only serve as one of many guides to Tristan, they also have a surprising link to one of the Alkean folk heroes.

In fact, having the Alkean characters brought into the real world also allows for teachable historical and modern moments that aren’t sugarcoated for its younger audience. Instead, they say, “Look closer at the complicated world you’re living in, see its ugly racist roots, and then build something better.” Lessons like this often involve Tristan coming to a realization after using his powers to learn the untold stories of cities and places like New Orleans, Louisana, and Vicksburg, Tennessee. On the modern side of things, Tristan also encounters certain human individuals who are just as bad as King Cotton due to their desire to “discipline” Black kids by kidnapping them and stripping them of their spirits.

It is delightful to see how some of the Alkeans manage to adapt to the real world despite everything going on. A really cool facet of this is a group of children who form the skateboarding group called Rolling Thunder, partially as a refuge. With a new character, Grannie Z, watching over them and Thandiwe (the princess of Alke’s Isihlangu region) leading them, they are a pretty resolute and exciting bunch. There is also the contemporary version of High John’s spirit bird, Old Familiar, which has a coolness similar to Alke’s Story Box becoming a high-tech cell phone.

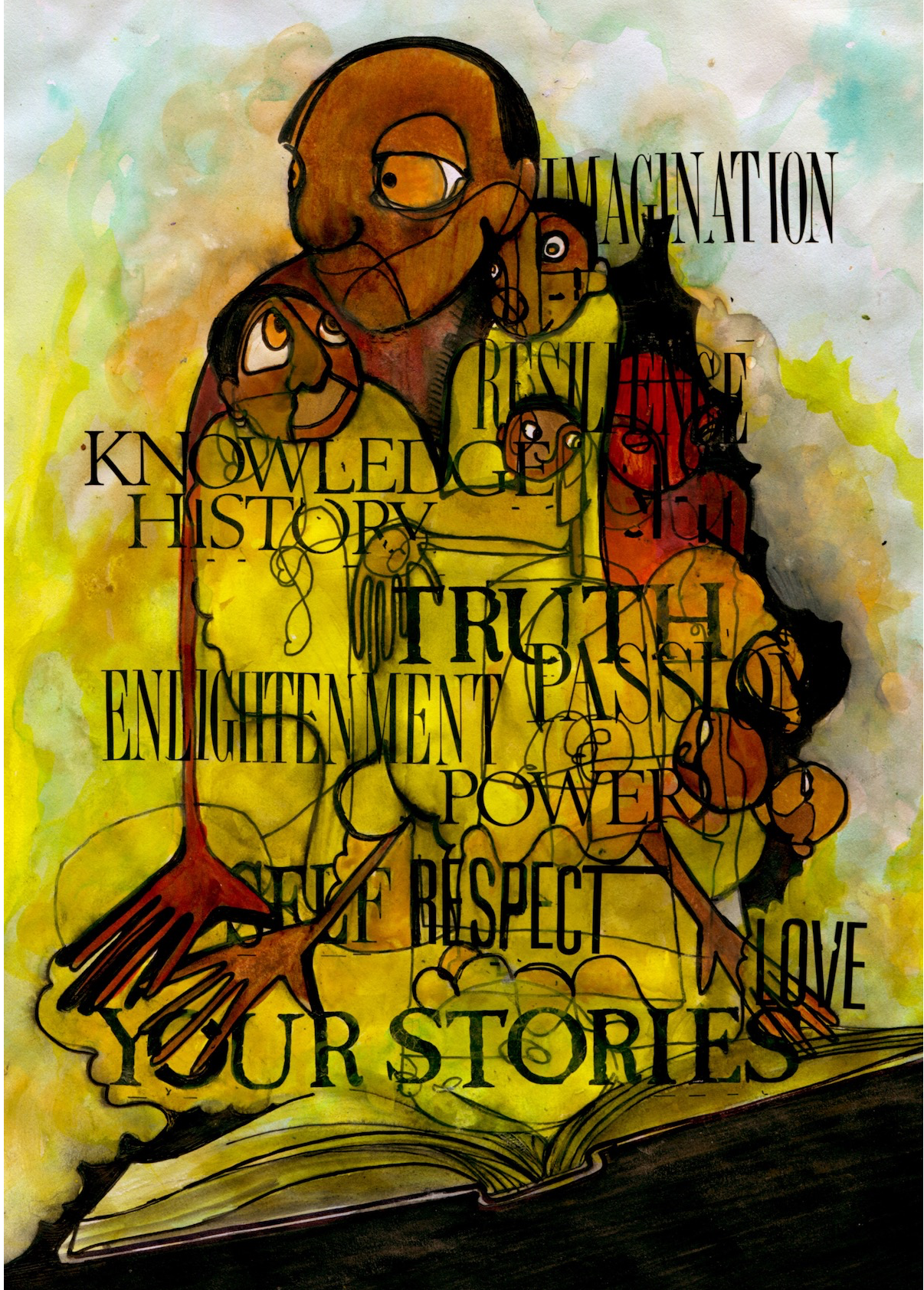

Both the past and present of the real world and the Alkeans allow for a variety of Black experiences to be shown in this novel. Moreover, these experiences are summed up in a beautiful allegory, “Black is a rainbow.” Black joy and Black pain are shown to be neither worse nor better than the other, but experiences that are connected and worth acknowledging. Despite the pain and hardship that Black people have experienced and continue to experience, we are also capable of fighting for and making our own Black joy. In fact, the character Gum Baby is probably one of the best embodiments of this, as she can literally fight and laugh at the same time.

In order for Tristan to fight for the past and present properly, he undergoes brilliant character development when he slowly confronts his anger in full. In the first book, Tristan Strong Punches a Hole in the Sky, Tristan’s anger is part of the grief he experiences after losing his best friend, Eddie. Now, Tristan’s anger isn’t just personal; it is felt by the entire community of Alkeans and amplified through their losses and untold stories. Since Tristan is an Ananseem, the anger of the Alkeans becomes his and manifests in a literal fire that Tristan must learn to control.

Given that the world often considers angry Black people to be threats, seeing Tristan learn to acknowledge and harness that anger is wonderful. Tristan puts it best when he says, “Anger uncontrolled is chaotic; anger given purpose is a tool.” Tristan shows that anger is multifaceted and a necessary emotion, because anger can fuel the desire to set wrong things right.

Not only is this book filled with amazing characters, real-life facts, and magic, but it is also a testament to resilience, surviving, and thriving. Tristan Strong Keeps Punching is an epic conclusion to the tale of Tristan Strong, burning bright and high.

The Afro YA promotes black young adult authors and YA books with black characters, especially those that influence Pennington, an aspiring YA author who believes that black YA readers need diverse books, creators, and stories so that they don’t have to search for their experiences like she did.

Latonya Pennington is a poet and freelance pop culture critic. Their freelance work can also be found at PRIDE, Wear Your Voice magazine, and Black Sci-fi. As a poet, they have been published in Fiyah Lit magazine, Scribes of Nyota, and Argot magazine among others.

We hoofed it up four long flights to the top floor and entered a living room with fourteen-foot ceilings and balconies that opened up to a spectacular view. It spanned from the Capitólio, a near-identical replica of the U.S. Capitol building, across the lush green treetops of the Granma Memorial and out to the malecón, the famous sea wall that marked the edge of the island.

We hoofed it up four long flights to the top floor and entered a living room with fourteen-foot ceilings and balconies that opened up to a spectacular view. It spanned from the Capitólio, a near-identical replica of the U.S. Capitol building, across the lush green treetops of the Granma Memorial and out to the malecón, the famous sea wall that marked the edge of the island. So, after all of these years, I found myself standing on the tile floors of a nearly century-old building in Habana Vieja, the oldest part of Havana, saying yes to the purchase.

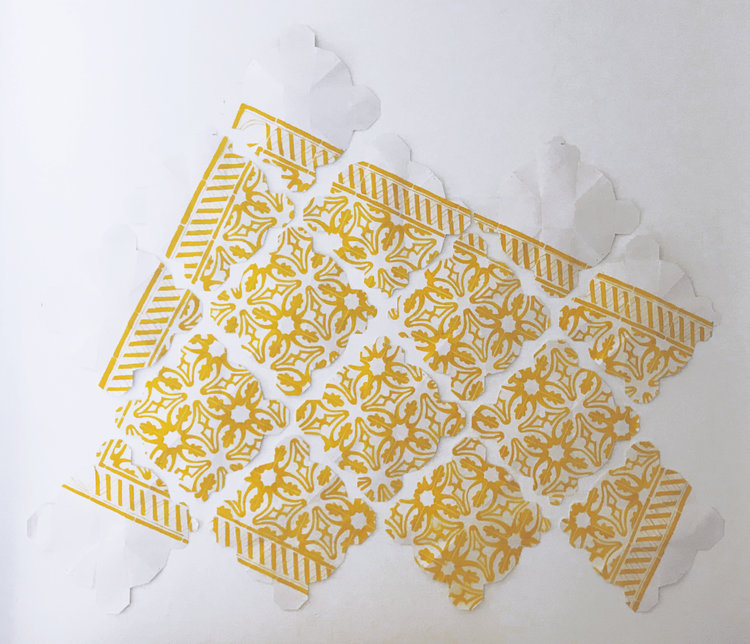

So, after all of these years, I found myself standing on the tile floors of a nearly century-old building in Habana Vieja, the oldest part of Havana, saying yes to the purchase. Cuban tiles—referred to losas hidráulicas or mosaicos—were first brought from Spain

Cuban tiles—referred to losas hidráulicas or mosaicos—were first brought from Spain

Recent Comments