National Poetry Month Contest Winners 2023

National Poetry Month Contest Winner 2023

Sujash PurnaPicking a poem from so many poems shared during National Poetry Month is always so difficult—how to set something experimental and free-versed against a tight form and judge one “better” when they reach for such different things?

While selecting a group of poems was no easier this year, the pleasures of reading were multiplied by being able to engage with a group of poems from each poet: to trace their voices through several poems, see how the notion of cycle translated from one to the next, how a subject could be visited across forms (sometimes turned inside out) or explored in concentric layers of complexity. Thank you for sharing your work—you turned me inside out, made me look again and again at what you were pointing to: be it a hummingbird, or a spare portrait in words, or the tangled mythologies of culture complicated by list forms.

For the winning selection, Sujash Purna’s poems “You Poor” begin with bludgeon lines, tender lines, sequestered on a page of negative space. Of the four poems, the variety in forms move from that spareness to a discursive voice-driven plea where the line endings deliver with a power that insists on being read aloud. The repetition of “your” and the breaking of “your” fragment not only the imperative to speak, but the self who speaks. In the final poem, the strategies of the first three coalesce: spareness, space, repetition, and concrete detail to connect the earlier poems in the cycle to each other, and to connect more fully to the reader.

Other noteworthy poets sharing their poem groupings include:

Ellie Lamothe’s “A Funeral in March,” “If We’re Honest,” and “Litany”

J.F. Merifield’s “Portraits”

Devon Balwit’s “Notes on Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers [II-V]”

—C. Kubasta, Editor, BMP Voices Poetry Month

Winner

“You Poor” Cycle by Sujash Purna

1.

.

.

.

.

I’m never going to see my mom again

…………………………………………………………………………..I am too poor to do that

2.

.

People in Missouri

don’t know who

I am anymore

.

.

.

.

People in Dhaka

don’t know who

I am anymore

.

.

People where I

am now

.

don’t

.

want to know

There Must Be Something Wrong

.

Visually nothing is aesthetic

It’s the lens they put on you

And tell you that this is how

You should look at this thing

That will neither make you

Happy nor circumvent your

Danger unless you tell your

-self yourself yourself your

Self to believe in the story

That they built based on

Your struggles, based on

Your sacrifices, based on

Your absences from your

Loved ones. Even the

Word love has become

Corrupt. It’s how they

Want you to feel. Not

How you feel. Because

If you feel that way

There must be something

Wrong. There must be

Something wrong. There

Must be something wrong.

Inductive Reasoning for a Family

.

glycerine drops

.

psoriasis-looking spots

.

your hair

a harsh sun

this master’s degree minimum wage job

that phd holder adjunct gig

two kids

two parents

their

health care

who cares?

you do

yours?

who cares?

you’re on your own now

you’re on your own now

you’re on your own now

You Poor III

.

I don’t write about flowers and lovers anymore

I write about shit that went out of control

Not the white people Babylon

Or American Hustle kind of coke-infused

Out of control

.

I write about being in a place

Where nobody wants you

Paycheck-to-paycheck immigrant

Renewal-to-renewal immigrant

Paying-double-the-tax immigrant

Taking-half-the-benefits

Taking nothing because

I should be already

Thankful

Immigrant

Short List

“A Funeral in March,” “If We’re Honest,” and “Litany” by Ellie Lamothe

A Funeral in March

.

I belong to the cold bones of winter.

Bare-skinned, barren, and remembering

the sound of your laugh like a funeral bell.

The sound of the boreal wind

whispering through the pines,

a wisdom for our children and their children,

and the ones they will love

without knowing why.

The gentle grief of living one evening to the next,

exchanging one ending for another.

I want to leave my brittle body behind,

become lost in the brume,

a spectre collecting light

and sadnesses leftover from years before.

Still, I am willing to endure.

I am willing to endure.

If We’re Honest

.

it’s a miracle that we come together at all,

that romance

is ever more than a formality

between two unreliable narrators of their own suffering.

We became accustomed to the taste of saltwater,

learned to perform that ritual

of kind pittances,

found a peculiar lightness

in clinging to the soft things.

My body, clumsy and pitted,

lingering in the cold sweat of your body.

Several vital organs missing

between the two of us.

You tell me your sadnesses in a voice

so sweet and perplexing,

I almost forget hunger

and the way it blooms

violet like a bruise along my jaw.

I almost forget to cherish

the way your throat opens up when you laugh.

Now everything we do is imaginary.

And I fear our love, too,

is just in our heads.

So I touch you to make it real,

and slowly,

to untangle the solemn etymology of desire,

and the terrible things

we endure out of loneliness

The terrible things we do to the people

we are trying to love.

You peel my clothes off in the dark room

and I let you.

But touching me becomes an unnatural thing

with our bones bleached.

The ceremonial undoing,

by some despondent architect of quiet endings

Litany

.

I am sitting cross legged on a pier,

bargaining with the stillness of the morning.

Having no one to mourn

my body as it acquiesces,

surrenders memory (even the dear ones),

becomes the fog hanging low over the lake.

I am thinking about things too bleak

for the morning

and the delicate charms of its first light.

The temporality of bliss

and the reasons I have been unkind.

I am learning there is nothing constant

but the wintering

and warming of desires,

how even ordinary wounds can fester.

I am learning about curiosity

and too, about hunger,

from the ruby-throated hummingbird

and her relentless need to move toward something.

A tender certainty.

The medicinal commonalities

between sugar water and song.

You don’t sing for me

and I begin to keep some of my sadnesses to myself.

Even then, I don’t pretend to love silence

the way you do.

So this is how it goes.

We suffer,

and we owe,

and we rejoice

in the delicate light of dawn,

in the surrendered memory,

in the hummingbird and her hunger.

And each day

we sit at the mouth of the lake

and recite our own litany of yearning.

Ellie Lamothe is a poet living in K’jipuktuk (Halifax, NS) with her cat Arabella. She’s passionate about feminism, addressing gender-based violence, and engaging in community care through her role at a local women’s shelter. She loves going for walks with an iced matcha latte, being cozy, listening to Celtic music while she writes, and playing Dungeons and Dragons. Her work has appeared in Glass: A Journal of Poetry (Poets Resist), Kissing Dynamite, Yes Poetry, and Ghost City Review, among others. You can follow her on Instagram @ellielamothe.

Short List

“Portraits” by J. F. Merifield

Portrait as Lost Calf

.

the barbed wire and dirt road sing

together of dust, of dry grass

.

tanning in the wind

on sun-swept

hills that roll away

.

from an unmulched garden

left to wild,

its nature becoming its own

Portrait as Hunger

.

the wind holds the hawk

still

above the ditch

no field mouse

nosing out just yet

the hunt afoot

all the same

a patient moment

an urge held

aloft

Portrait as Landscape Painting Titled: Night Flying Over Winter Mountains

.

the moon full

illumines

marbled mountains

snow-pearled

and forest black.

squiggled lines

where light and dark

touch

splinter

wrinkle

ripple

thirty-one thousand feet below.

Portrait as Impressionist Painting of the Seine River Bank Titled: Communique

.

my mind is a weighted hook

plunging through waves

of quells and quivers,

each distant image a one-piece

unshouldered one side at a time,

down to the hips for now,

factually speaking boats float

and “the sun always seems to be

your friend not mine,”

Guillemots sings,

so I count the waves

rolling on to shore,

warily we have spoken

of where the two meet,

saturating one another, these moments

fit us, as in exposing to each we see

there is thread tethered,

hooked at both ends.

J.F. Merifield, a poet living in northwest Montana with a Poetry M.F.A. from George Mason University, has poems published by Wild Roof Journal, High Shelf Press, Sheepshead Review, Cathexis Northwest Press, La Picciolette Barca, Neuro Logical, Verse, and Rust & Moth, among others.

Short List

“Notes on Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers [II-V]” by Devon Balwit

Notes on Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers [II]

.

1. What is it like to walk in the arrogance of one’s own beauty?

2. We lesser lights suspect mockery.

3. Coupled with the gift of prophesy and a diaphanous robe, it is too much.

4. Who could blame our plots and spite-dug pit,

5. our preference for small gods to one vaster than telling.

6. Our gods are amenable to thimble-sized offerings, atonements of human measure.

7. Why serve the ineffable, suffering blindness

8. when comfort can be found in the dark?

Notes on Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers [III]

.

The favorite son knows nothing

about jealousy, cannot imagine anyone

loving him less than he loves himself,

ignorant of how his very shadow sears

like coals, of how his dulcet voice

brays in our ears, or of the paths

we furrow in our dreams, each tracing

a different murder, a different exile,

a hoe against his skull, a shearing knife

to his testicles, eager for even one

of our father’s tears to vault

as a rich and much-awaited inheritance.

Notes on Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers [IV]

.

Do you love humankind? the angel asks.

What a question for even a favorite son to answer.

We love what loves us back, what is easy

to love, what passes the time. We usually smile

at one another, the boy says, the rest of humanity

and I. Despite near divinity, the angel smirks. How little

the lad has been thwarted. Later, much later,

the angel will ask again and receive a changed reply.

For now, he merely accompanies the boy

to the future, that doorway to heartbreak

through which every soul steps.

Schadenfreude: Notes on Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers [V]

The angels … were created in Our image, yet are not fruitful…[T]he beasts are fruitful, yet are not after Our likeness. We will create man—in the image of the angels, and yet fruitful!

1. Once again, creation disappoints.

2. The angels flutter a vast gloat.

3. Hadn’t they warned יהוה embodied souls could only blunder?

4. Even the cherubs suspected wombs would only gestate frustration.

5. Still, יהוה pursued his puny and petulant shadows.

6. Part of the problem, the favorite son observes the tutting echelons,

7. dazzled as they scintillate—uncountable gossiping mouths.

Devon Balwit’s work appears in The Worcester Review, The Cincinnati Review, Tampa Review, Barrow Street, Rattle, Sierra Nevada Review, and Grist, among others. Her most recent collections are We Are Procession, Seismograph [Nixes Mate, 2017], Dog-Walking in the Shadow of Pyongyang [Nixes Mate Books, 2021] and Spirit Spout [Nixes Mate Books, 2023]. For more, visit https://pelapdx.wixsite.com/devonbalwitpoet

Editors’ Choice, Week 4

“Ekundayo (Daughter When You Read This…),” “Survivor Series,” “Pray for Me,” and “Inner Child” by Donnie Moreland

Ekundayo (Daughter, When You Read This…)

.

I’ll begin with a sermon on empty pill bottles,

a full tub and desperation.

I’ll begin with a confession — a lot of niggas don’t make it here.

I’ll begin with the ground beneath my daddy’s feet rotating like a crooked wheel,

keeping him in place but spreading him apart

like the black hole between my teeth and

each letter in the declaration, “I’m going to kill myself.”

I called him first.

I’ll begin with the semicolon on my right wrist.

I’ll begin as your father.

I’ll begin where Pa Pa refused to say your daddy’s name in the past tense.

You began because he refused our finale.

I’ll begin with his rebuttal.

I’ll begin with his love.

A love swollen between wounds and cures.

Fear and fire.

Gore and glory.

A love.

Love.

I’ll begin with love.

And somewhere along the way, we’ll figure out that joy part.

Survivor Series

.

My father used to wrestle me.

Pin me.

Raise my legs and count to three.

I laughed, in defeat.

Each holler covers the distance between the cosmos in creation.

We don’t talk much now.

I feel his hand on my shoulder when I wrestle my daughter — the pressure of falling onto a bed

or into birth — and I turn to reverse his maneuver.

But he’s not there.

Just the marbled monument to a tag team comeback that never was.

We don’t talk much now.

But luckily, ghost stories don’t always belong to the dead.

Pray for Me

.

Say a little prayer for the boy.

For me.

For him.

And his men.

Say a little prayer for his father.

His father’s keeper.

And his keeper still.

Say a little prayer for the boy.

And if you can, say another.

Inner Child

.

I hope that boy inside you…

the one kicking his feet in the air, hollering at cartoon characters and

eating cotton candy in Crayola crayon castles,

picking his nose and

dirtying his pant legs while running shoeless

to the corner store…

I hope that boy still triumphs over his archnemesis.

I hope he’s still doing somersaults on wood chips

where the splinters jab deepest.

I hope that boy still pulls on fire alarms and opens closet doors to evil empires in need of a champion.

I hope that boy still throws himself down rolling hills, under a pink sunset and a white moon.

I hope that boy knows his golden grin is still heaven.

Donnie Denkins Moreland Jr is a Houston-based health educator and multidisciplinary artist. Donnie holds a Master’s Degree in Film Studies from National University and a Bachelor’s Degree in Sociology from Prairie View A&M University. Donnie’s work centers cultural healing, black masculinities, and film criticism. Donnie has contributed to Black Youth Project, Brown Sugar Literary Magazine, RaceBaitr, Root Work Journal, A Gathering of the Tribes, Unmute Magazine, and Sage Group Publishing.

BMP Celebrates National Poetry Month

As the pandemic has continued into its second year, we at Brain Mill are thinking about spaces & places: how we exist in space, the importance of access, and the particulars of navigating places. We have gathered together in ways that may have been new to us over the last few years, greeting each other in small squares of connectivity, developing relationship and care with virtual check-ins, follows, and voices translated via technology. In our best moments we have learned to listen; in our worst, we have been caught up by all the ways we need to do better and think more deeply about community systems and for whom entry is barred.

About the Editor

C. Kubasta writes poetry, fiction, and hybrid forms. Her most recent book is the short story collection Abjectification. She supports her creative work as Director of Education at Shake Rag Alley Center for the Arts in Mineral Point, Wisconsin. Find her at ckubasta.com and follow her @CKubastathePoet

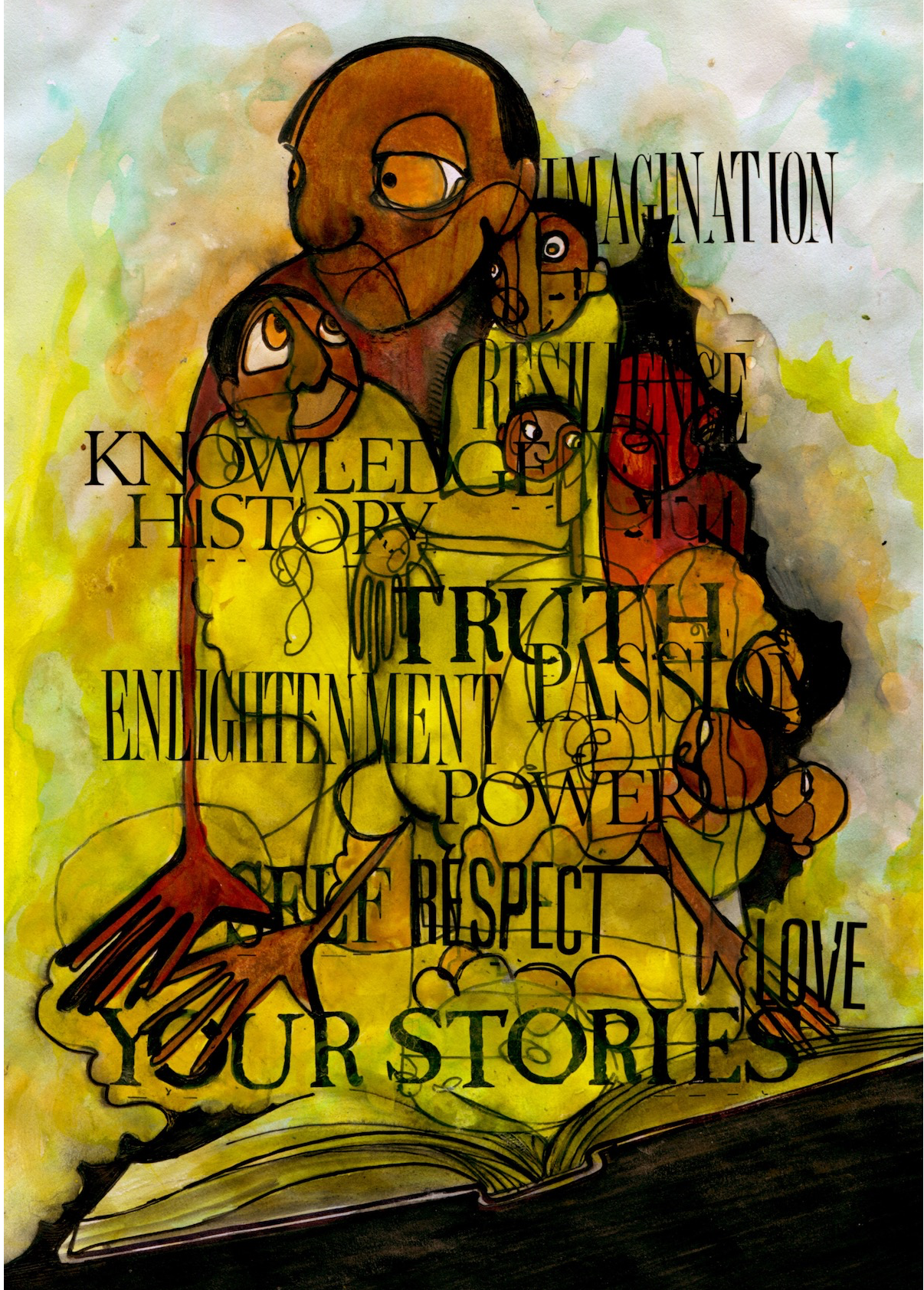

Top photo by Jill Burrow

Recent Comments