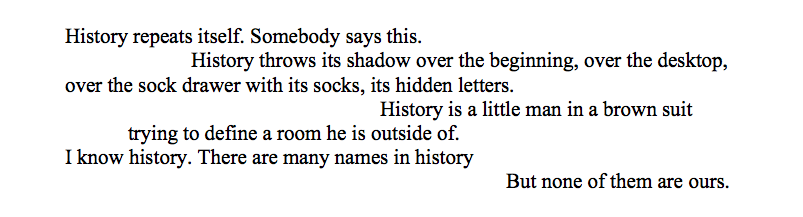

In it, she includes some long lines from Siken’s poem “Litany in Which Certain Things Are Crossed Out” as an example of end-stopped lines satisfying and furthering desire. Reading just those few lines made me want to read the entire poem; reading the entire poem made me want to read it aloud; reading it aloud made me want to read it aloud for an audience—and so on.

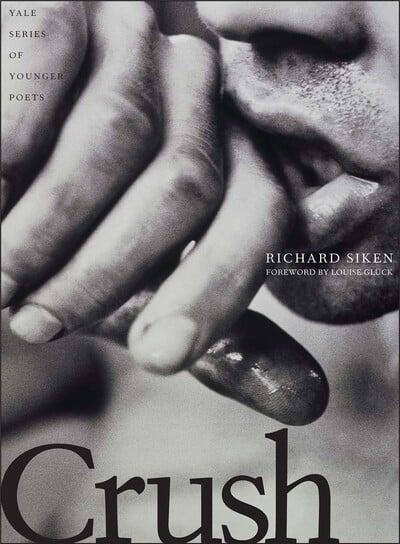

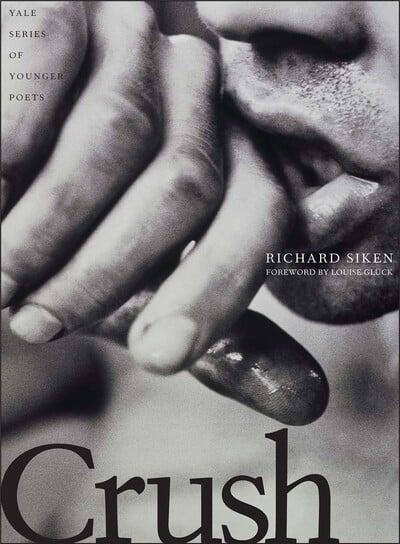

When, early in March, we began to spend most of our time apart—in our respective homes, in front of computer screens instead of people, texting and calling to connect virtually rather than face-to-face—I ordered novels and short story collections and poetry to feed the part of myself that missed friends, family, colleagues, and students. I tried to keep a schedule for the first few weeks, and it included live poetry readings in the quiet of my home, my dog attentive beside me. The books I lingered over, reading and re-reading, were poems that spoke of touch, vulnerability, bodies that comfort and confuse, pain that rises in words on the page and that, in a deft poet’s tongue, forces us to see the world in its trauma and longing. Those were Richard Siken’s first collection, Crush, and the excellent anthology edited by Cam Awkward-Rich and sam sax, The Dead Animal Handbook.

When, early in March, we began to spend most of our time apart—in our respective homes, in front of computer screens instead of people, texting and calling to connect virtually rather than face-to-face—I ordered novels and short story collections and poetry to feed the part of myself that missed friends, family, colleagues, and students. I tried to keep a schedule for the first few weeks, and it included live poetry readings in the quiet of my home, my dog attentive beside me. The books I lingered over, reading and re-reading, were poems that spoke of touch, vulnerability, bodies that comfort and confuse, pain that rises in words on the page and that, in a deft poet’s tongue, forces us to see the world in its trauma and longing. Those were Richard Siken’s first collection, Crush, and the excellent anthology edited by Cam Awkward-Rich and sam sax, The Dead Animal Handbook.

Crush begins with the poem “Scheherazade”—the title invokes that story that encompasses all stories, the story that keeps us alive. Its final lines are: “Tell me how all this, and love too, will ruin us. / These our bodies, possessed by light. / Tell me we’ll never get used to it.” In its beginning, this book of poems points to the dangers of desire, and the way desire can save. What draws me to Siken’s work is the long lines, and how they refuse the limits of the page. They range and ramble, as if any constraint—other than the speaker’s voice—is to be shed whenever useful. Within stanzas (although not traditional stanzas) the logical connections between content and imagery prove fundamentally useless as well. This too makes sense—those constrictions would shackle the poems. In these poems about desire (and sometimes the destruction inherent in desire) what does it matter if there’s a pattern to where the mind goes—if the apple has much to do with the windowpane? Or if the bodies being pulled out of the lake make much sense in the poem that ends with “bodies, possessed by light”? Each poem is both utterly inscrutable (being painfully personal) and ultimately universal (speaking to the unknowable we’ve each known if we’ve known the) experience of incendiary desire.

There are so many poems that must be read aloud here: “Dirty Valentine” makes its rounds regularly on social media—inhabit its I’s, and you’s, and we’s. In “Little Beast,” the speaker claims a space for himself, invoking the everyday domestic:

The long prose poem “You Are Jeff” is a masterpiece. It imagines, alternately, different Jeffs. There are twins named Jeff—riding motorbikes “shiny red” and both with “perfect teeth, dark hair, soft hands.” They are options, these Jeffs. “The one in front will want to take you apart, and slowly [ . . .] The other brother only wants to stitch you back together [ . . .] Do not choose sides yet.” In later sections, you are one of the Jeffs, on the motorbike, and you’re either coming up a hairpin turn or just beyond it. In another, “You are playing cards with three Jeffs. One is your father, one is your brother, and the other is your current boyfriend. All of them have seen you naked and heard you talking in your sleep.” In another, you are without any Jeffs, but there is an empty space next to you, and in the poem—after all those Jeffs—the reader feels that emptiness, palpable.

In the penultimate section of the poem, we’re back on the side of the road. There have been Jeffs everywhere—some a comfort, some a riddle, some a menace, some a part of the speaker, some a faint outline barely knowable. On the side of the road are motorbikes, and Jeffs, God and the Devil, and spaces between them. “Two of these Jeffs are windows, and two of these Jeffs are doors, and all of these Jeffs are trying to tell you something.” The poem ends, “You’re in a car with a beautiful boy . . .” and the speaker and the boy love each other, but neither will say it. “ . . . he reaches over and he touches you, like a prayer for which no words exist, and you feel your heart taking root in your body, like you’ve discovered something you don’t even have a name for.”

I think what keeps me returning to Siken’s poems is the mix of the passion, sometimes mad-rush of the lines, with the juxtaposition of crystalline transcendent imagery right next to the very human, almost mundane. It’s there in that first poem I read. “Love always wakes the dragon and suddenly / flames everywhere. / I can tell already you think I’m the dragon.” (Okay, I understand this voice—allusion and undercutting.) And then—“And yes, I swallow / glass, but that comes later. / And the part where I push you flush against the wall . . .” (Confessional, but pointed.) But a little later, “The entire history of human desire takes about seventy minutes to tell. / Unfortunately, we don’t have that kind of time. / Forget the dragon, / leave the gun on the table, this has nothing to do with happiness.” Siken’s honesty, in the poem’s language, in lines dictated by breath, speak to me in these times of distance and isolation. I want poems that reach out like that, palpable.

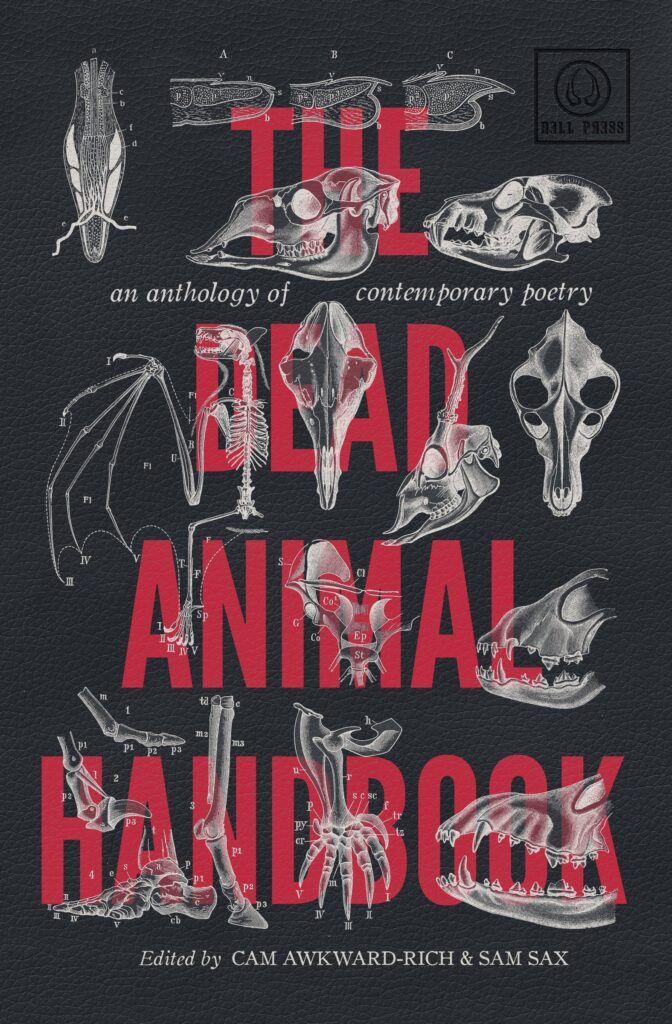

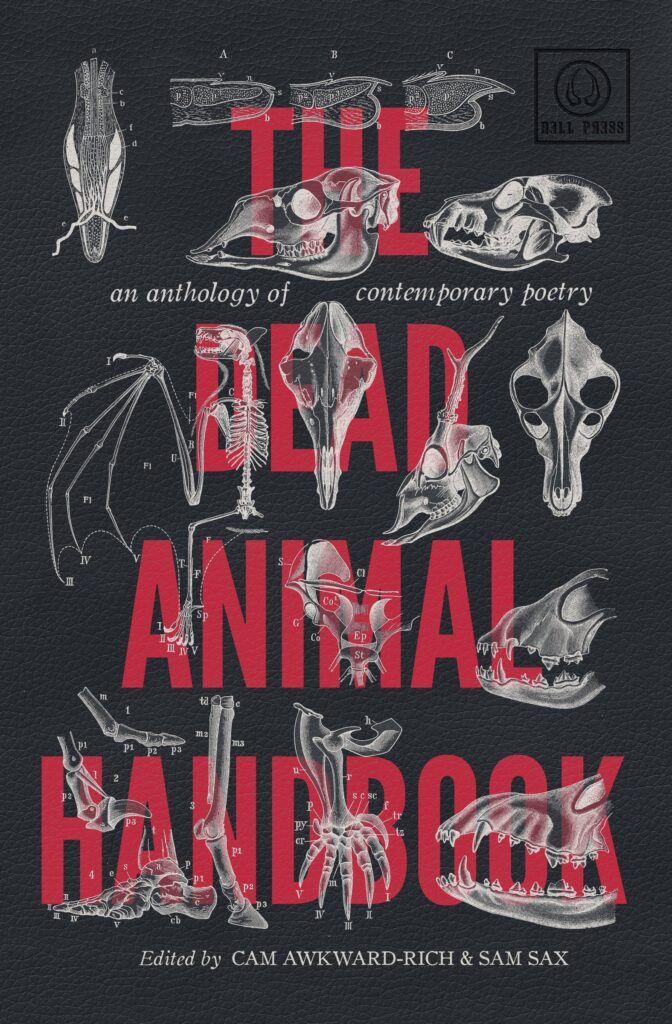

The anthology The Dead Animal Handbook, from University of Hell Press, takes a cue from this kind of poetry too, utilizing the imagery of animals—dead and gone—to foreground our humanity, or lack of it. In the introduction, editors Cam Awkward-Rich and sam sax write, “Rather than simply rejecting animality in order to claim humanity, many of these poems embrace the animal as a way of understanding the racialized, gendered, or sexual self, or in order to model forms of resistance.” Organized, in part, around the kinds of animal imagery in the poems (from birds, to fish, cats or dogs, or cattle), the included names are a wide selection of American poets—including important black and brown poets, and queer poets—as the editors put it, the “not straightwhitemen” of contemporary literature. Additionally, there’s a good mix of award-winning and well-known poets, alongside less-well-known poets—and since the collection came out in 2017, several contributors have become much more prominent.

The anthology The Dead Animal Handbook, from University of Hell Press, takes a cue from this kind of poetry too, utilizing the imagery of animals—dead and gone—to foreground our humanity, or lack of it. In the introduction, editors Cam Awkward-Rich and sam sax write, “Rather than simply rejecting animality in order to claim humanity, many of these poems embrace the animal as a way of understanding the racialized, gendered, or sexual self, or in order to model forms of resistance.” Organized, in part, around the kinds of animal imagery in the poems (from birds, to fish, cats or dogs, or cattle), the included names are a wide selection of American poets—including important black and brown poets, and queer poets—as the editors put it, the “not straightwhitemen” of contemporary literature. Additionally, there’s a good mix of award-winning and well-known poets, alongside less-well-known poets—and since the collection came out in 2017, several contributors have become much more prominent.

A number of the poems juxtapose animal bodies with human bodies, the treatment and handling of different kinds of bodies to sharpen those distinctions. Two that stood out for me were Danez Smith’s “Juxtaposing the Road Kill & My Body” and Deborah A. Miranda’s “Deer.” In both, it’s the aftermath—the final lines of the poems—that deliver their lingering power, their afterimage that demonstrates a poem’s power to nurture as it bears evidence of (attempted) destruction. In Smith’s poem, short and slight stanzas have each captured “the difference”—the difference between the speaker and the deer—the difference between being hit by a car and a rape. Each of these is brutal, some more so because of their forthrightness, and the final stanza contains “A man, emptied of his voice / & drawers ruined & sweet with grenadine, / is called a myth or a bitch or not a man at all.” The irony of this powerful voice invoking the idea of voicelessness. Miranda’s poem contrasts an out-of-season kill, furtively butchered, that “all winter long we’ll eat [ . . ] / in secret.” The speaker for “years afterward” visited “the stained floor” in the barn. In the final (almost separate) stanza, she writes: “I’ve been taken like that: / without thanks, without a prayer, by hands / that didn’t touch me the way a gift should be touched, / knives that slid beneath my skin out of season / and found only flesh, only blood.”

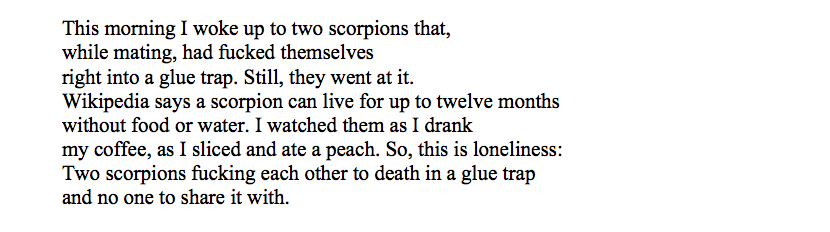

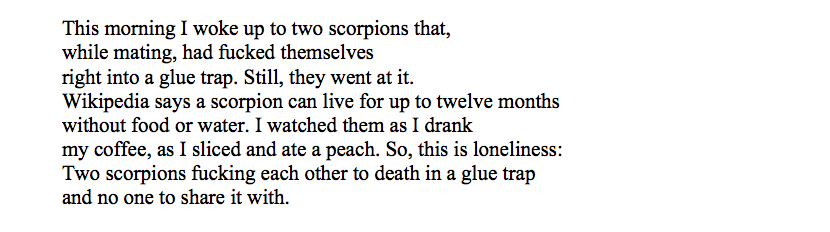

Not all the poems in the anthology catalogue trauma—there are also mini-manifestos here. Oliver Bendorf’s “Precipice” declares, “I don’t farm for milk. I farm for the front row / seat to things living and dying.” In “The Dogs and I Walked Our Woods,” by Gretchen Primack, there’s a grisly “monument to domination” in the woods—two coyotes killed and displayed—and the speaker swears that if she had a child who might suffer to see such a thing, or be gladdened to see such a thing, or just keep walking, “I could not bear / it, so I will not bear one.” There is also some dark humor, a wry moment of recognition, clear-eyed, the way these poets see the world, like Meg Freitag’s “Promenade A Deux”:

The collection is also an example of fine editing; the juxtaposition and sequencing of poems deepen their resonances with each other, leading to a between-the-pages conversation. One of the most startling is between Dominique Christina’s “Hunger” (on page 75) and Erich Haygun’s “Love Is Like Walking the Dog” (on 76). In the latter, dog-walking is an extended metaphor for maintaining a relationship, where “picking up shit” is evidence of care and maintenance. The final line speaks of a relationship that’s outlived its usefulness, or maybe one where there’s no love or regard; but the speaker goes on cleaning up, “even if the dog is dead.” The poem on the preceding page tells of the beating and destruction of a dog, one that wouldn’t stop howling. A few well-placed words detail killing the dog, “killing and killing the siren call of want. / simple.” The dog wouldn’t stop, and the speaker couldn’t take it anymore, “I’m the one who is hungry bitch. ME.”

Um. I don’t know what to do with the above except to tell you I went back and re-read those two poems together several times. (I had already stopped reading aloud to the dog next to me on the couch—it seemed unkind.) I’m in awe of words that stop me, make me stare ahead unfocused, make me roll my tongue in my mouth to try to discern the power of language and how it comes. Maybe the dog is dead. Maybe love is doing things anyway. Maybe sometimes you have to kill the dog. Maybe when I see the bodies pulled out of the lake I think of your body, and tenderness, and the ultimate vulnerability of lying with you and loving you. Maybe I’m the dragon. Okay, I’m not the dragon, but maybe I want to be. Okay, maybe I just want to be able to write like these poets, or to find these poems and be able to fit them into a book and know how they’ll reach someone sitting on a couch in Central Wisconsin, spooning their mastiff-mix, wanting and wishing that sometime soon we’ll be able to touch each other again and maybe feel something other than fear and emptiness inside, paralyzed because we don’t know what to do. I guess maybe I’d just like you to read some of these poems. In the final poem of Crush, “Snow and Dirty Rain,” there are these lines:

Because we’re all looking for the story that’ll save us, the poem to keep us alive.

Because we’re all looking for the story that’ll save us, the poem to keep us alive.

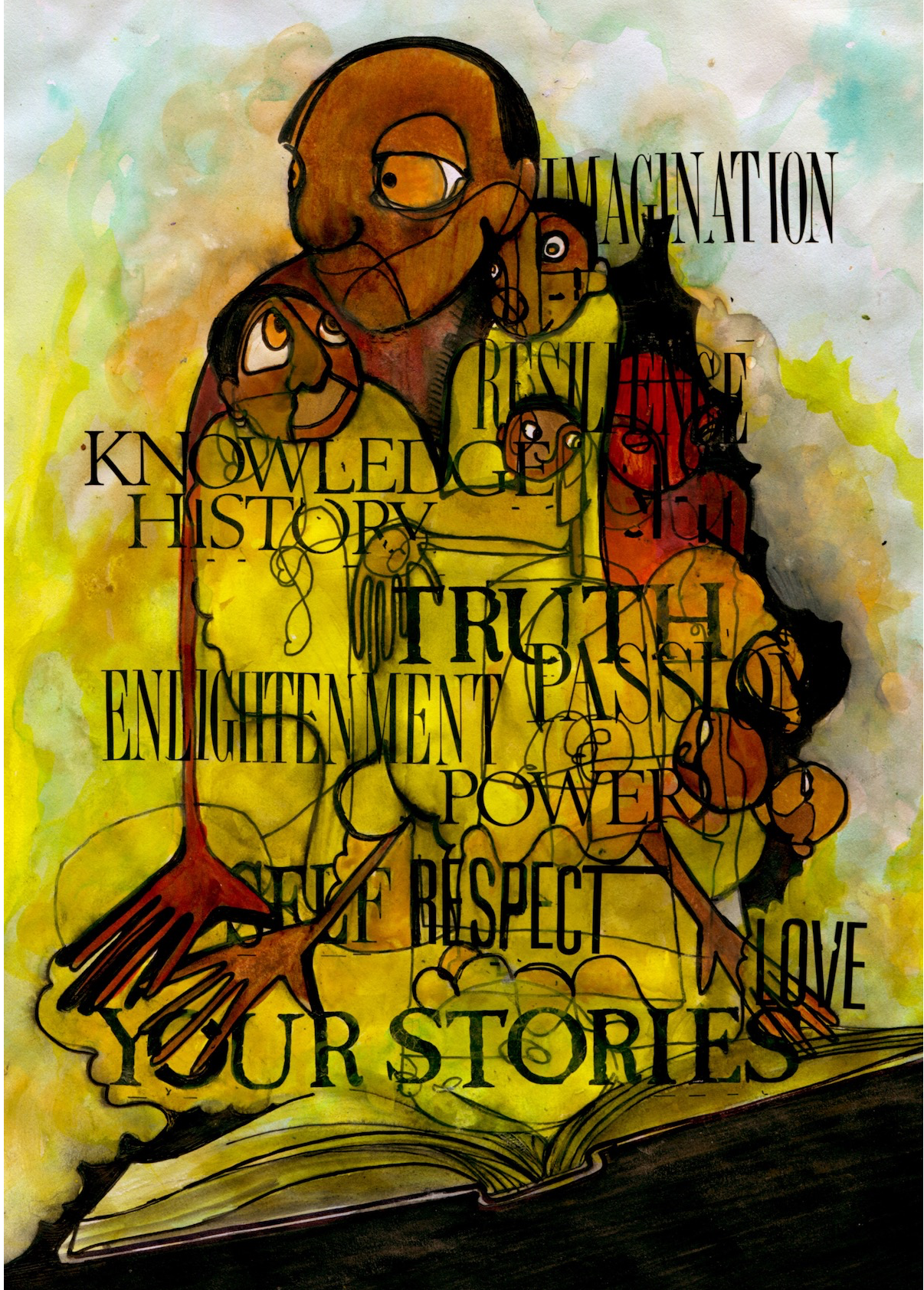

Tristan Strong is a twelve-year-old boy grieving the loss of his best friend, Eddie, and smarting from being defeated in his first boxing match. While visiting his grandparents’ farm in Alabama, he accidentally unleashes an evil haint and creates a hole between the real world and a magical world of African American folk heroes and West African gods. Now he must work together with them and undergo an epic quest to retrieve Anansi’s story box to save the world.

Tristan Strong is a twelve-year-old boy grieving the loss of his best friend, Eddie, and smarting from being defeated in his first boxing match. While visiting his grandparents’ farm in Alabama, he accidentally unleashes an evil haint and creates a hole between the real world and a magical world of African American folk heroes and West African gods. Now he must work together with them and undergo an epic quest to retrieve Anansi’s story box to save the world.

Jack Ellison King is an African American teen who never quite succeeds at important milestones. When he meets Kate on the steps of a house party, he’s hoping to somehow succeed at romance. Then Kate tragically dies of an illness, and Jack is sent back in time to the day they met. Given the second of many chances, Jack strives to prevent Kate’s death while weighing the consequences of his choices and the people he chooses to be with.

Jack Ellison King is an African American teen who never quite succeeds at important milestones. When he meets Kate on the steps of a house party, he’s hoping to somehow succeed at romance. Then Kate tragically dies of an illness, and Jack is sent back in time to the day they met. Given the second of many chances, Jack strives to prevent Kate’s death while weighing the consequences of his choices and the people he chooses to be with.

What I notice each time I re-read the book is how the poet’s voice and memories are bound up with her mother’s. Section One begins with her mother, “My mother lived on a moshav,” and tells how that came to be through the stories of the previous generation: an old British airport hangar, but before that a grandmother in a prison camp in Palestine, and before that both grandparents’ arrival by boat, and before that Romania. In the midst of these early pages, these primal stories, the poet tells us her mother’s first memory, “a dog barking behind a screened door, its mouth full of sharp teeth and drool, its legs taller than her three-year-old self.” Kopernik then makes the all-encompassing move, “her memory could have been any year, any country.” What child doesn’t have some terrifying memory lodged somewhere, what child doesn’t remember some beast at the door? It is the twining of these — these small anywhere-moments with the larger stories of families making and re-making, migrating & moving — that accomplishes the large and small of The Memory House. Two pages later, we are granted the title line, after more moments that refract the mother’s memories through the poet-daughter’s voice: “Our memories tangle into a single memory house.”

What I notice each time I re-read the book is how the poet’s voice and memories are bound up with her mother’s. Section One begins with her mother, “My mother lived on a moshav,” and tells how that came to be through the stories of the previous generation: an old British airport hangar, but before that a grandmother in a prison camp in Palestine, and before that both grandparents’ arrival by boat, and before that Romania. In the midst of these early pages, these primal stories, the poet tells us her mother’s first memory, “a dog barking behind a screened door, its mouth full of sharp teeth and drool, its legs taller than her three-year-old self.” Kopernik then makes the all-encompassing move, “her memory could have been any year, any country.” What child doesn’t have some terrifying memory lodged somewhere, what child doesn’t remember some beast at the door? It is the twining of these — these small anywhere-moments with the larger stories of families making and re-making, migrating & moving — that accomplishes the large and small of The Memory House. Two pages later, we are granted the title line, after more moments that refract the mother’s memories through the poet-daughter’s voice: “Our memories tangle into a single memory house.”

Interspersed between these memory-moments are love poems, which seem to be about both finding one’s person as well as finding the self. The structure of moving between the early childhood poems and the adult poems make sense, as they suggest another kind of knowing and coming of age. The clarity of the language rings true: “I want this body / finally mine, naked, covered / in glitter and chicken feathers.” It is straightforward and defiant and joyful, tinged with the awful fantastic. Soon though, the beloved becomes a source of worry – long before the poem-story begins to hint at how the dissolution will happen, the speaker hints at meaningful differences between them; her girlfriend is a police officer, and the speaker wonders about her job, things she may have to do. “How will you see this world / with your gun? Is there anything / we can protect?” This too ties back to the childhood poems, when the poet tries to understand her father. In the poem “Inside Me” the reader sees the father, over and over again – in his chair, smoking, hauling rocks, always working. This poem is one of those that ranges across the page, with little breaks for breath, few guideposts of phrasing or punctuation. It ends with the resonant line: “there he is inside me singing what a surprise when I realize it’s not a song but a sob” – there’s no period. The poem ends, but it doesn’t end. The sob catches in the throat, nowhere to go.

Interspersed between these memory-moments are love poems, which seem to be about both finding one’s person as well as finding the self. The structure of moving between the early childhood poems and the adult poems make sense, as they suggest another kind of knowing and coming of age. The clarity of the language rings true: “I want this body / finally mine, naked, covered / in glitter and chicken feathers.” It is straightforward and defiant and joyful, tinged with the awful fantastic. Soon though, the beloved becomes a source of worry – long before the poem-story begins to hint at how the dissolution will happen, the speaker hints at meaningful differences between them; her girlfriend is a police officer, and the speaker wonders about her job, things she may have to do. “How will you see this world / with your gun? Is there anything / we can protect?” This too ties back to the childhood poems, when the poet tries to understand her father. In the poem “Inside Me” the reader sees the father, over and over again – in his chair, smoking, hauling rocks, always working. This poem is one of those that ranges across the page, with little breaks for breath, few guideposts of phrasing or punctuation. It ends with the resonant line: “there he is inside me singing what a surprise when I realize it’s not a song but a sob” – there’s no period. The poem ends, but it doesn’t end. The sob catches in the throat, nowhere to go. Tara Shea Burke is a queer poet and teacher from the Blue Ridge Mountains and Hampton Roads, Virginia. She’s a writing instructor, editor, creative coach, and yoga teacher who has taught and lived in Virginia, New Mexico, and Colorado. She believes in community building, encouragement, and practice-based living, writing, teaching, and art. She is the author of the poetry book Animal Like Any Other, from Finishing Line Press (2019). Find more about her work and

Tara Shea Burke is a queer poet and teacher from the Blue Ridge Mountains and Hampton Roads, Virginia. She’s a writing instructor, editor, creative coach, and yoga teacher who has taught and lived in Virginia, New Mexico, and Colorado. She believes in community building, encouragement, and practice-based living, writing, teaching, and art. She is the author of the poetry book Animal Like Any Other, from Finishing Line Press (2019). Find more about her work and  When, early in March, we began to spend most of our time apart—in our respective homes, in front of computer screens instead of people, texting and calling to connect virtually rather than face-to-face—I ordered novels and short story collections and poetry to feed the part of myself that missed friends, family, colleagues, and students. I tried to keep a schedule for the first few weeks, and it included live poetry readings in the quiet of my home, my dog attentive beside me. The books I lingered over, reading and re-reading, were poems that spoke of touch, vulnerability, bodies that comfort and confuse, pain that rises in words on the page and that, in a deft poet’s tongue, forces us to see the world in its trauma and longing. Those were Richard Siken’s first collection,

When, early in March, we began to spend most of our time apart—in our respective homes, in front of computer screens instead of people, texting and calling to connect virtually rather than face-to-face—I ordered novels and short story collections and poetry to feed the part of myself that missed friends, family, colleagues, and students. I tried to keep a schedule for the first few weeks, and it included live poetry readings in the quiet of my home, my dog attentive beside me. The books I lingered over, reading and re-reading, were poems that spoke of touch, vulnerability, bodies that comfort and confuse, pain that rises in words on the page and that, in a deft poet’s tongue, forces us to see the world in its trauma and longing. Those were Richard Siken’s first collection,

The anthology The Dead Animal Handbook, from University of Hell Press, takes a cue from this kind of poetry too, utilizing the imagery of animals—dead and gone—to foreground our humanity, or lack of it. In the introduction, editors Cam Awkward-Rich and sam sax write, “Rather than simply rejecting animality in order to claim humanity, many of these poems embrace the animal as a way of understanding the racialized, gendered, or sexual self, or in order to model forms of resistance.” Organized, in part, around the kinds of animal imagery in the poems (from birds, to fish, cats or dogs, or cattle), the included names are a wide selection of American poets—including important black and brown poets, and queer poets—as the editors put it, the “not straightwhitemen” of contemporary literature. Additionally, there’s a good mix of award-winning and well-known poets, alongside less-well-known poets—and since the collection came out in 2017, several contributors have become much more prominent.

The anthology The Dead Animal Handbook, from University of Hell Press, takes a cue from this kind of poetry too, utilizing the imagery of animals—dead and gone—to foreground our humanity, or lack of it. In the introduction, editors Cam Awkward-Rich and sam sax write, “Rather than simply rejecting animality in order to claim humanity, many of these poems embrace the animal as a way of understanding the racialized, gendered, or sexual self, or in order to model forms of resistance.” Organized, in part, around the kinds of animal imagery in the poems (from birds, to fish, cats or dogs, or cattle), the included names are a wide selection of American poets—including important black and brown poets, and queer poets—as the editors put it, the “not straightwhitemen” of contemporary literature. Additionally, there’s a good mix of award-winning and well-known poets, alongside less-well-known poets—and since the collection came out in 2017, several contributors have become much more prominent.

Because we’re all looking for the story that’ll save us, the poem to keep us alive.

Because we’re all looking for the story that’ll save us, the poem to keep us alive.

Recent Comments