On Small and Unusual Spaces

On Small and Unusual Spaces

by Valarie Frost

Place has always been a complicated topic for me to grasp; to hold still in the palm of my hand.

To paraphrase the big moves in my life: I was adopted from China when I was one year old, raised in the suburbs of Portland, Oregon, toured the country as a teenager, and currently reside on the East Coast. Like a horizonless kaleidoscope that transforms endlessly in the light of every slight angle, unusual spaces are the conceptual nodes of a life perceived in remnants. As I write and compile an anthology of sorts about the tiny spaces I’ve inhabited physically, and emotionally from afar, the notion of place morphs into something inconceivably intangible, riddled with the what-ifs of my yesteryears. In spaces where circumstance and spontaneity intersect, the room to vastly dissect notions of self is created.

Small spaces define us because they allow us to reorient ourselves in a reality defined by the fixed settings we’re born into. They brush the tips of our noses, scrape our knees, and we jam our heads into a child’s tactile realm. Defined as we are by the nooks within our larger sense of presence, the composition of our environment dwindles, and we realize that composition itself is indivisible from our situational locus. The center of these small spaces, the gooey impalement in our sternum, is all we have in the long run. To investigate and write about the chimera that are these tiny spaces of emotional heat is to write about the times in between that bridge the present and past; trail markers of our identity. They create us. As someone who’s spent a decent amount of time traveling in these in-between zones, tethered in the liminality of my personal collection of tiny and unusual spaces, I’ve come to learn that spaces are what we take with us after the fact. Small spaces serve as plot points for us to retrace. They’re these ethereal reference points that allow us to lay out ourselves like a character out of a novel.

I used to believe that escaping physically from a place could also release you emotionally—that location alone could ripen the eye and honey the world. But distance only temporarily files down familiarity with the freshness of an unblemished sight. Regardless of where we are, we tend to seek out the same functions of comfort, whether that be the type of crowd we attract or the items we accumulate over time. It makes me think about great writers like the Bronte sisters or Thoreau, who barely traveled far yet still managed to capture the essence of the human condition. Their work interrogates the necessity of excessive travel, but in many ways our civilization today is anchored differently than that of previous decades. Instead of solitude as a choice or purely a condition, solitude has become a form of escapism—the dream we chase after and the chase we dream of.

I used to believe that escaping physically from a place could also release you emotionally—that location alone could ripen the eye and honey the world. But distance only temporarily files down familiarity with the freshness of an unblemished sight. Regardless of where we are, we tend to seek out the same functions of comfort, whether that be the type of crowd we attract or the items we accumulate over time. It makes me think about great writers like the Bronte sisters or Thoreau, who barely traveled far yet still managed to capture the essence of the human condition. Their work interrogates the necessity of excessive travel, but in many ways our civilization today is anchored differently than that of previous decades. Instead of solitude as a choice or purely a condition, solitude has become a form of escapism—the dream we chase after and the chase we dream of.

From Portland, Oregon, to Boston, Massachusetts, and the unavoidable places in between, travel has always carried an air of distinguishment. The idea of getting a fresh start when you change location is part of an allegory I fell for. With my collection of friend groups, town squares, and signals of a sunny day, I watch closely as they evolve in parallel spaces and often see them develop past myself. I am attentive as time goes on and as I stop to look back. The places I’ve been become alternate timelines of sorts; evidence of what could’ve been. Places move on without you, without permission, but spaces solidify your experience of a place, the space you choose to inhabit or choose to acknowledge or choose to identify with. I’ve become infatuated with tiny and unusual spaces because although they are engrained in the physical world, the value of solitude is all in our heads.

My sense of place was impacted a handful of years ago when my family sold my childhood home and moved out of state. My experience influences my piece particularly heavily because it was a tear in my sense of belonging and broke the bordered shelter that is home. On my last night in town, I was driving home, and I decided to do one last round to all the places that were meaningful to me that I knew I wouldn’t get to see again for the foreseeable future—

The wall of brick behind the high school where I’d pace on overcast days.

The wooded path of dead pines next to the old house.

The bog where I found a dead squirrel.

The nature park railroad only to be navigated at dusk.

The neighborhood tennis court where I gave someone a black eye.

The greenspace that fueled the children with endless dandelions.

The dusty base beneath the acorn tree where all the outcasts went to play.

The panel of cement where I pulled a three-inch-long splinter out of my foot.

The chilled garage step where I told my Mom I was leaving.

The patch of hallway where I built a trebuchet using floss.

The back deck where I dyed my dog hot pink.

The carpeted corner where I hid from my future.

The space underneath my desk where I stored jars of peanut butter.

The shelf of my headboard that hid my embarrassment.

The wooden stage I performed on with my sister when we were close.

The pillow we declared was only to laugh into at night.

The skylight in ‘Grandma’s bedroom’ that attracted soggy leaves and pale light.

The nerdy inside jokes that lined my mouth.

The back of the closet where I hid just to see if I could disappear.

The sitting branch where I engraved my sister’s and my names into the bark.

The yellow of a blazing day that crisped up the grass beneath my step.

The enormous oak tree that watched over us all.

My essay on tiny and unusual spaces began as an homage to these places and my determination for them not to be forgotten. Small spaces as they were and as we remember them are what we have to move forward with. They’re what we bring along with us. They are coveted planes that remind us of ourselves while allowing us to hide from the dexterity and daedal nature of our situation. While writing on this subject, I came across the word to hide frequently, and, unsurprisingly, I believe this is because isolation is so entangled with escapism. To escape is a luxury, and since we don’t always have the opportunity to run away, tiny spaces aid us in creating emotional bubbles where we can mentally detach from our everyday. Those are the kinds of memories that can resonate with us for a lifetime. Some of them, the ones I look back on often, even escape words. Their familiarity as a pocket of my reminiscence alone surpasses the value of the vision itself—the act of recollection becomes more sacred than what’s recalled. Those are the ones we love, the ones we return to in grim times, the ones that remind us of something we once were caught by. As a writer with this particular focus, to capture these instances is my mission. To let others into our enigmas and to provide reprieve embodies our ability to sympathize and to be understood.

Other spaces offer themselves to us more coyly, in which they only appear to us attached to other flashbacks. They demand us to scan our memory and to pluck out the blooms worth remembering. Only the finest, greenest, thoughts; almost as if we can fool ourselves into thinking that’s what the whole world is like. But when we begin to interrogate ourselves and to look forward in match time, we inherently look back at what we know, which comes in the form of these smaller-than-bite-sized crumbs of an internal space, of the actions we’ve already dotted, and of the experiences whose wholeness has come and gone. Within these small spaces that we recall and the more acute spaces that encompass our recollection of sentience, our lives are stitched together, and we begin to piece together an identity of our life lived.

About the Maker

From Beaverton, Oregon, Valarie Frost (she/her) is a non-fiction writer currently residing in Boston, Massachussetts. Her work centers around the environments we inhabit and the nuances of our perceived identities. She gained a degree in English specializing in Creative Writing from Simmons University and continues to write for local publications.

Akin to many writers, her relationship with writing stems from its ability to heal and to navigate the past. In blurring genre lines, she sees memory as an ever-morphing figure that changes with each recollection. She believes that through the kaleidoscope of reflection, writing can mirror those reflections into the future and provide insight into framing the consequences of our being. In her free time she’s an avid hiker, bicyclist, aspiring climber, and strategist.

Photo by Vlado Paunovic from Pexels.

Like most working poets, I struggle to find time to write. Scribbles on receipts, napkins, the marginalia on work notes, texts to myself, email drafts. The skeins of poetic fragments continued to pile up. In my upcoming book,

Like most working poets, I struggle to find time to write. Scribbles on receipts, napkins, the marginalia on work notes, texts to myself, email drafts. The skeins of poetic fragments continued to pile up. In my upcoming book,

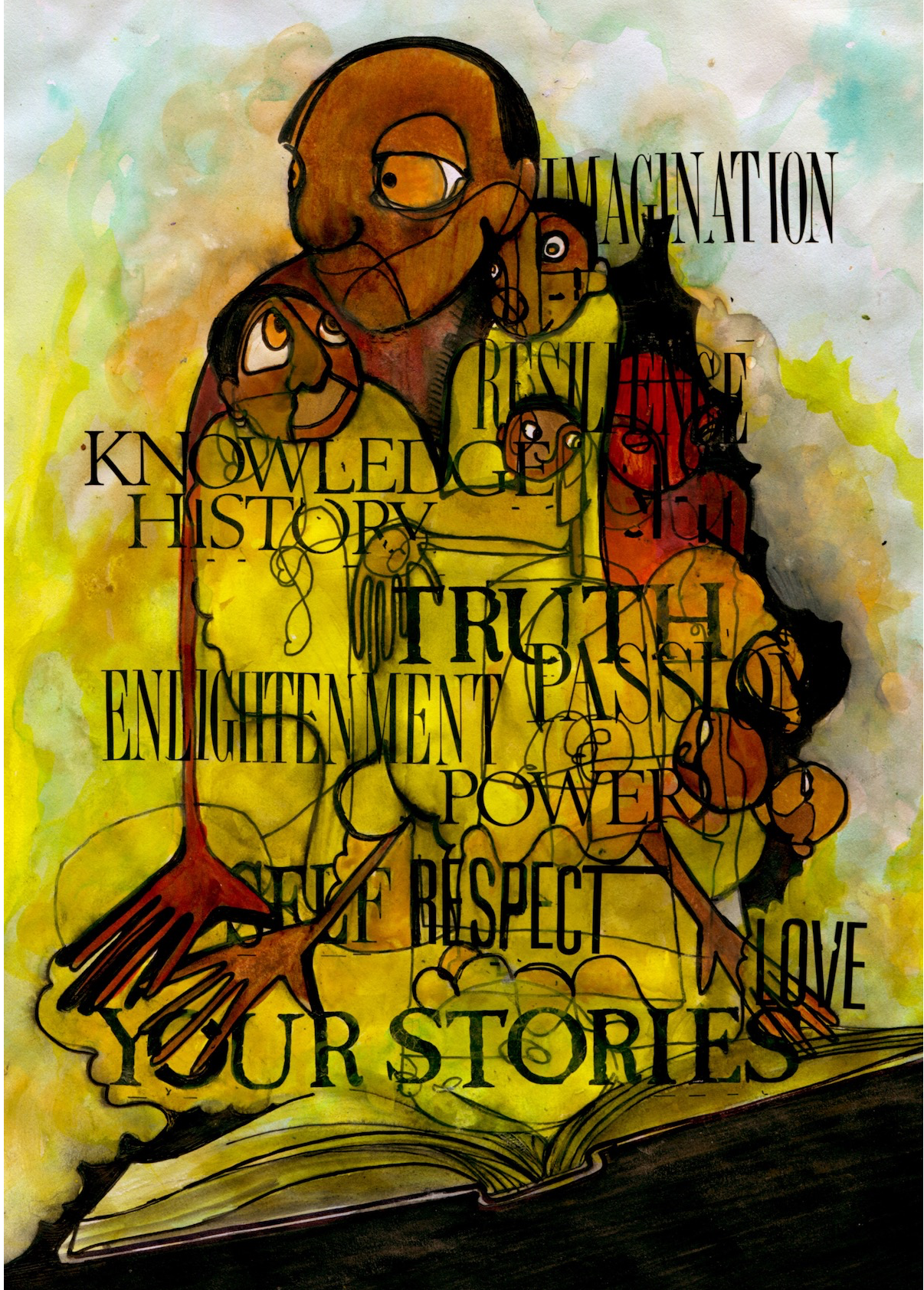

This is more of a collection of poems and visual art than a novel in verse, but I’m including this book because it’s become one of my new favorites. Using the Golden Shovel poetry form, Grimes takes one line or short poem from a Black female Harlem Renaissance poet and uses it to make her own poem. The book itself is formatted so you read the Harlem Renaissance poem first and then the poem it inspired Grimes to write. Each set of poems is also accompanied by visual art by Black women, including Vashanti Harrison and Shada Strickland. As a whole, the poetry and illustrations work together to bridge the past and present.

This is more of a collection of poems and visual art than a novel in verse, but I’m including this book because it’s become one of my new favorites. Using the Golden Shovel poetry form, Grimes takes one line or short poem from a Black female Harlem Renaissance poet and uses it to make her own poem. The book itself is formatted so you read the Harlem Renaissance poem first and then the poem it inspired Grimes to write. Each set of poems is also accompanied by visual art by Black women, including Vashanti Harrison and Shada Strickland. As a whole, the poetry and illustrations work together to bridge the past and present. Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds

Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds Every Body Looking by Candice Ihoh

Every Body Looking by Candice Ihoh

Recent Comments