Pride Spotlight: Black Queer YA

Pride Month Spotlight: Black Queer YA

June is Pride Month. With the pandemic still affecting the economic situation of LGBTQ people and current legislation negatively affecting trans youth, it may seem we don’t have much to celebrate.

Yet the fact that we continue to survive, fight, and triumph in small and large ways is worth being happy about. One of the most notable things is the rise of Black LGBTQ+ authors in young adult fiction.

A decade ago, the only Black queer author I knew of who wrote teen fiction was Jacqueline Woodson. Now I can name at least a dozen authors. From verse novels to fantasy, Black LGBTQ+ authors have been leaving a colorful mark for a new generation to see. Check out some of the Black queer YA books I’ve enjoyed over the past few years.

The Black Veins by Ashia Monet

by Ashia Monet

Nothing says summer like a road trip, even a world-saving one. This is what happens to Blythe Fulton, a Black bisexual Elemental Guardian, after her family is kidnapped and taken to the Trident Republic. Of course, she can’t rescue her family on her own, so she must recruit other Elemental Guardians to help her.

In addition to the magic and action, I really enjoyed the downtime the characters experience in this book. The friendship is so fun and heartwarming, especially because there is some flirting but no romance whatsoever.

Felix Ever After by Kacen Callender

Felix Ever After by Kacen Callender

Not only is this book set during Pride Month in NYC, but it is also about a Black trans demi boy learning to have pride in himself. After his pre-transition photos are leaked, Felix Love must find the culprit while reexamining who he is and the kind of love he wants from others.

Felix’s personal journey is poignant because it shows that one’s gender identity isn’t necessarily set in stone after coming out. Furthermore, it demonstrates the importance of standing up for who you are, even if it means having hard conversations with friends and family.

The Summer of Everything by Julian Winters

The Summer of Everything by Julian Winters

Spending summer working in a bookstore may seem like a lot of fun, especially when it’s a safe space. But what if the bookstore is in danger of closing? Eighteen-year-old Wesley Hudson deals with this with the used bookstore Once Upon a Page. Not to mention, he is struggling to plan his older brother’s wedding, figure out his future plans, and confess his crush on his best friend, Nico Alvarez.

All of these things are a part of something that Wesley has been avoiding: adulthood. As Wesley deals with a lot over the course of the novel, he manages to figure out what is most important to him with the help of a colorful cast of characters.

Let’s Talk about Love by Claire Kann

Let’s Talk about Love by Claire Kann

Being in college is difficult, especially when your girlfriend breaks up with you for being asexual. On top of that, Alice is also trying to figure out her career path. Things become even more complicated when she ends up with a crush on her new library co-worker Takumi. What’s a Black biromantic girl to do?

This book lives up to its title as Alice figures out what she loves to do in order to identify her future career and redefine what love means, both romantically and in terms of friendship. Not only does this book show how complex love can be, it also shows that it’s worth discussing and exploring with others.

Magnifique Noir by Briana Lawrence

Magnifique Noir by Briana Lawrence

College-aged everyday young women by day. Magical girls by night (and sometimes day too). This is the basic premise of Magnifique Noir, a book series about a Black queer team of magical girls. The first book in the series focuses on gamer girl Bree Danvers and boxer Lonnie Knox as they take their first steps as magical girls alongside baker Marianna Jacobs, who is the most experienced of the three.

The second book copes with the aftermath of the first and demonstrates the importance of mental health and taking care of yourself. Both feature short comics and colorful art that enhance the narrative and give the sparkly antics extra shine. They also tackle certain experiences in a mature manner, such as misogynoir, difficult parents, and online trolls.

The Black Flamingo by Dean Atta

The Black Flamingo by Dean Atta

My favorite definition of poetry is “imagination written in verse.” When this definition is applied to verse that tries to define the poet’s self, the verses themselves become a source of power. This is the case with The Black Flamingo, which tells the story of Michael Angelis, a Black British gay man with Greek-Jamaican heritage.

Through performance and verse, Michael blossoms beautifully as we read his story from childhood to burgeoning young adulthood. By using a flamingo as a metaphor to figure himself out, Michael learns to stand out and be proud.

The Afro YA promotes black young adult authors and YA books with black characters, especially those that influence Pennington, an aspiring YA author who believes that black YA readers need diverse books, creators, and stories so that they don’t have to search for their experiences like she did.

Latonya Pennington is a poet and freelance pop culture critic. Their freelance work can also be found at PRIDE, Wear Your Voice magazine, and Black Sci-fi. As a poet, they have been published in Fiyah Lit magazine, Scribes of Nyota, and Argot magazine among others.

Top photo by Anete Lusina from Pexels

Raised by a strict, religious Christian father and separated from her alcohol-addicted mother, Ada wants to take her life into her own hands but isn’t sure how to go about it. Due to past trauma and her shaky upbringing, she is so focused on other people’s expectations of her that she hasn’t really considered what she wants for herself.

Raised by a strict, religious Christian father and separated from her alcohol-addicted mother, Ada wants to take her life into her own hands but isn’t sure how to go about it. Due to past trauma and her shaky upbringing, she is so focused on other people’s expectations of her that she hasn’t really considered what she wants for herself. This is more of a collection of poems and visual art than a novel in verse, but I’m including this book because it’s become one of my new favorites. Using the Golden Shovel poetry form, Grimes takes one line or short poem from a Black female Harlem Renaissance poet and uses it to make her own poem. The book itself is formatted so you read the Harlem Renaissance poem first and then the poem it inspired Grimes to write. Each set of poems is also accompanied by visual art by Black women, including Vashanti Harrison and Shada Strickland. As a whole, the poetry and illustrations work together to bridge the past and present.

This is more of a collection of poems and visual art than a novel in verse, but I’m including this book because it’s become one of my new favorites. Using the Golden Shovel poetry form, Grimes takes one line or short poem from a Black female Harlem Renaissance poet and uses it to make her own poem. The book itself is formatted so you read the Harlem Renaissance poem first and then the poem it inspired Grimes to write. Each set of poems is also accompanied by visual art by Black women, including Vashanti Harrison and Shada Strickland. As a whole, the poetry and illustrations work together to bridge the past and present. Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds

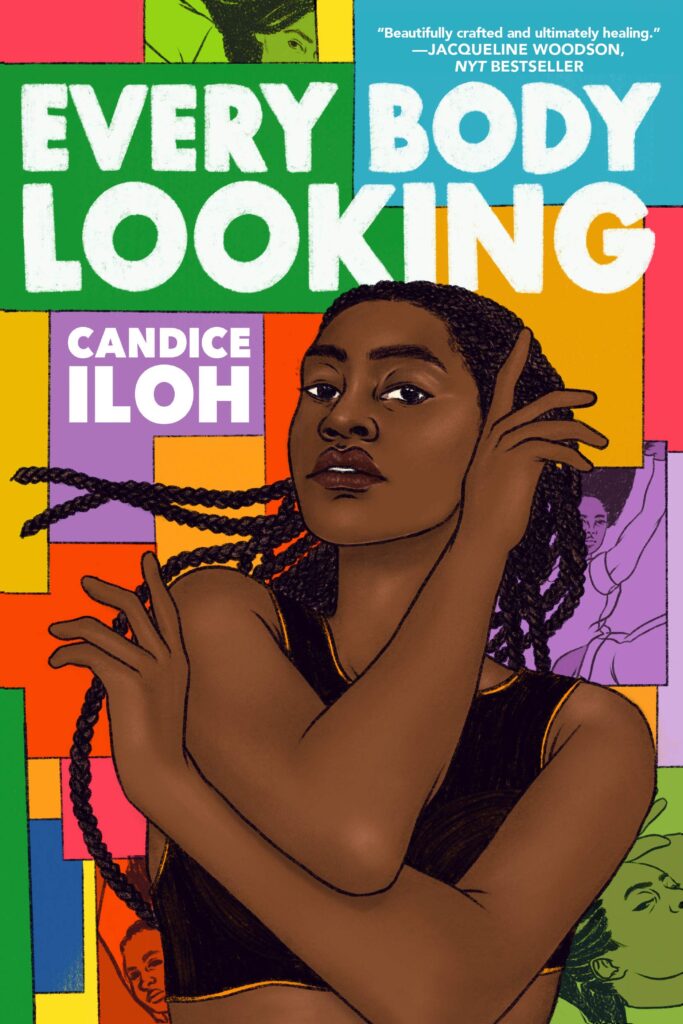

Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds Every Body Looking by Candice Ihoh

Every Body Looking by Candice Ihoh

Recent Comments