“Tiffany Sly Lives Here Now” Is a Dark Story of Family, Trauma, and Resilience

"Tiffany Sly Lives Here Now" Is a Dark Story of Family, Trauma, and Resilience

Content Warning

This review contains discussion of parental abuse, ableism against people with autism, alopecia, colorism, and racism.

After her mother’s death, sixteen-year-old Tiffany Sly goes to live with the family of Anthony Stone, her biological dad. However, Tiffany also has a secret: another man named Xavier Xavion thinks he might be her real dad, and he wants her to do a DNA test with him in seven days. With her life upended in more ways than one, Tiffany must make sense of who and what family could truly mean.

Speaking of families, one of the areas where this book shines is that it features a found family as well as a biological one. A found family is the family you make for yourself, as opposed to the family you were born into. Tiffany Sly gains a found family through her neighbors, a Black lesbian beautician named Jo Walton and her eccentric yet wise and kind son, Marcus. Jo Walton becomes a surrogate mother to Tiffany, allowing her to maintain her pride as a dark-skinned Black young woman and giving her a safe space to be herself. Marcus gives Tiffany the space to question how she feels about spiritual faith and death.

By contrast, Tiffany’s biological family is mostly awful, especially her father, Anthony Stone. Whether it’s because of his own self-hatred, his religious faith as a Jehovah’s Witness, or a combination of this with his own upbringing, Anthony Stone is a toxic and abusive parent for almost the entire book. As a light-skinned, mixed Black man who upholds respectability, he discriminates against or punishes anyone who does not fit his ideal, including his own family and his Black neighbors. When he first meets Tiffany, he demands she take out her braids even though they are her protective hairstyle for alopecia, a hair condition she developed due to stress and trauma. A few pages later, he also punishes his youngest daughter, Pumpkin, for being a person with autism.

Stone’s oldest biological daughter, London, is almost as bad as her father. Caught between a desire to please her family and rebel against them, she belittles or ignores Tiffany for most of the book. When London and Tiffany first meet, she makes a rude, colorist comment about how dark Tiffany’s skin is. Later, she films Tiffany falling on the basketball court and then shares the video with her friend, who uploads it with racist overtones added in. Although London swears she didn’t want things to go that far due to how her dad monitors his children’s social media, this is a really flimsy excuse.

Stone’s oldest biological daughter, London, is almost as bad as her father. Caught between a desire to please her family and rebel against them, she belittles or ignores Tiffany for most of the book. When London and Tiffany first meet, she makes a rude, colorist comment about how dark Tiffany’s skin is. Later, she films Tiffany falling on the basketball court and then shares the video with her friend, who uploads it with racist overtones added in. Although London swears she didn’t want things to go that far due to how her dad monitors his children’s social media, this is a really flimsy excuse.

In fact, the only family member with minor redeeming qualities is Anthony Stone’s wife, Margaret. Before Tiffany arrived, Margaret went along with whatever Anthony did in order to keep up appearances and prevent Anthony from being too harsh with her. Once Tiffany starts trying to make an effort to understand Anthony and his family more, however, she helps Margaret care for Pumpkin in a way that doesn’t trigger Pumpkin’s autistic meltdowns. Margaret, in turn, is helps Tiffany to understand Anthony’s past with Tiffany’s bio mom, Imani.

In addition to showing how complicated family can be, the book also portrays mental health, grief, and trauma in an authentic light, especially through the character of Tiffany herself. Some of her most memorable internal dialogue showcases her anxiety in a variety of situations, such as riding an airplane or a car. The way Tiffany’s anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder are portrayed, moreover, breaks the stigma surrounding mental health by normalizing taking medication to manage ongoing conditions. Also, Tiffany’s alopecia demonstrates how trauma can affect your physical as well as your mental health.

Yet Tiffany Sly is so much more than her trauma and mental illnesses. She is shown to have a deep love of music as a guitarist; some of the best dialogue has her waxing poetic about albums by The Beatles or the artistry of Nina Simone and Gershwin. Tiffany is also shown to be both a daughter and a granddaughter through her relationships with family members, especially her deceased mother, Imani. Although Imani isn’t physically present in the book, her time with Tiffany lives on through flashbacks and one surprise that brought tears to my eyes.

In fact, Tiffany Sly’s personality and character growth are the sole reasons I was able to keep reading this book. Although Tiffany experiences great hardship, she manages to pull through thanks to her kindness toward her found family and her gradually increasing compassion for Anthony Stone’s family, which grows from her desire for a father. But Tiffany deserves a better bio family than the one she ends up with, and she deserves a chance to choose who she calls her family. As a survivor of an emotionally abusive parent, I can’t say that I was completely comfortable with the ending to this book.

While this book tackles mental health, loss, and trauma beautifully, the toxic and abusive parenting of Tiffany’s bio dad nearly undoes all the progress Tiffany makes throughout the book. Due to how harmful Anthony Stone’s parenting is for most of the book, I can’t wholeheartedly recommend Dana L. Davis’s Tiffany Sly Lives Here Now to readers. For readers who do decide to pick up this book, be aware that this book contains triggering content.

The Afro YA promotes black young adult authors and YA books with black characters, especially those that influence Pennington, an aspiring YA author who believes that black YA readers need diverse books, creators, and stories so that they don’t have to search for their experiences like she did.

Latonya Pennington is a poet and freelance pop culture critic. Their freelance work can also be found at PRIDE, Wear Your Voice magazine, and Black Sci-fi. As a poet, they have been published in Fiyah Lit magazine, Scribes of Nyota, and Argot magazine among others.

One of the most intriguing things about

One of the most intriguing things about

Felix Ever After

Felix Ever After The Summer of Everything

The Summer of Everything Let’s Talk about Love

Let’s Talk about Love Magnifique Noir

Magnifique Noir The Black Flamingo

The Black Flamingo Raised by a strict, religious Christian father and separated from her alcohol-addicted mother, Ada wants to take her life into her own hands but isn’t sure how to go about it. Due to past trauma and her shaky upbringing, she is so focused on other people’s expectations of her that she hasn’t really considered what she wants for herself.

Raised by a strict, religious Christian father and separated from her alcohol-addicted mother, Ada wants to take her life into her own hands but isn’t sure how to go about it. Due to past trauma and her shaky upbringing, she is so focused on other people’s expectations of her that she hasn’t really considered what she wants for herself. This is more of a collection of poems and visual art than a novel in verse, but I’m including this book because it’s become one of my new favorites. Using the Golden Shovel poetry form, Grimes takes one line or short poem from a Black female Harlem Renaissance poet and uses it to make her own poem. The book itself is formatted so you read the Harlem Renaissance poem first and then the poem it inspired Grimes to write. Each set of poems is also accompanied by visual art by Black women, including Vashanti Harrison and Shada Strickland. As a whole, the poetry and illustrations work together to bridge the past and present.

This is more of a collection of poems and visual art than a novel in verse, but I’m including this book because it’s become one of my new favorites. Using the Golden Shovel poetry form, Grimes takes one line or short poem from a Black female Harlem Renaissance poet and uses it to make her own poem. The book itself is formatted so you read the Harlem Renaissance poem first and then the poem it inspired Grimes to write. Each set of poems is also accompanied by visual art by Black women, including Vashanti Harrison and Shada Strickland. As a whole, the poetry and illustrations work together to bridge the past and present. Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds

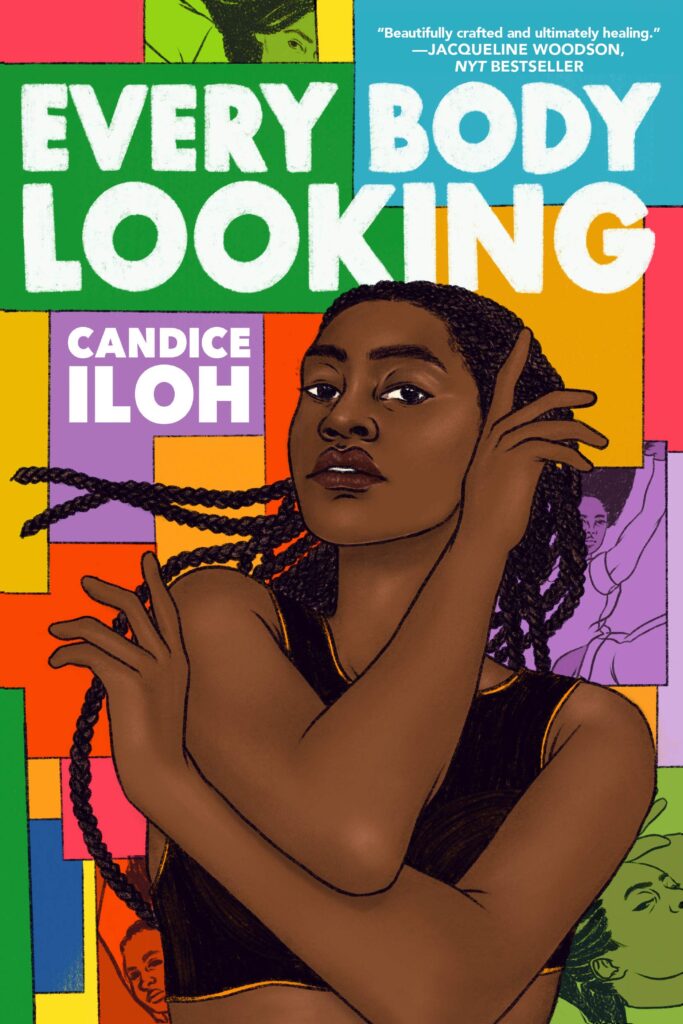

Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds Every Body Looking by Candice Ihoh

Every Body Looking by Candice Ihoh

Recent Comments