“The Black Flamingo” Is an Electrifying, Poetic Declaration of Identity

“The Black Flamingo” Is an Electrifying, Poetic Declaration of Identity

As a Black Asian nonbinary queer femme from the United States, I find it fascinating to learn about what life is like for queer trans people of color around the world.

Some countries have more queer freedom than others, but somehow international QTPOC always find a way to create a space to be themselves. This is exemplified in Dean Atta’s verse novel The Black Flamingo, which is heavily inspired by UK LGBTQ+ culture. It tells the story of Michael “Michalis” Angeli, a gay British young man with Greek Jamaican heritage. Growing up, his multifaceted identity makes him feel out of place. After deciding to attend a university in Brighton, Michael joins a drag club and slowly discovers how to combine his identities and his lived experiences to make himself feel whole.

One of the most notable aspects of this book that immediately drew me in was how it flawlessly combines standard poetry with narrative storytelling. As in Elizabeth Acevedo’s The Poet X, this book’s protagonist becomes a poet and gradually uses his poetry to express his blossoming sexuality as well as his gender and his racial experiences. One of my personal favorite poems in this book is titled “I Come From,” which features Michael reveling in his heritage and the experiences that have shaped him to that point: “I come from DIY that never got done. / I come from waiting by the phone for him to call. / I come from waving the white flag to loneliness. / I come from the rainbow flag and the Union Jack.”

The narrative storytelling in verse is also remarkable because it shows Michael’s life from childhood to early adulthood. I haven’t read too many coming-of-age verse novels that present the character at different stages of their life. This choice allows the reader to see how both small and large experiences shape Michael as he grows up. For example, Michael recalls wanting to have a Barbie doll as a child and how his mom initially thought he was kidding, since boys are socially conditioned to like “boys’ toys” like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. In a more affecting episode, preteen Michael takes an Easter trip to Cyprus and hears about a black flamingo on the news.

In fact, seeing how different experiences shaped the development of Michael’s drag character, “The Black Flamingo,” was thought-provoking and poignant. Inspired by events such as having his dreadlocks touched by white people and reciting his poetry at an open mic, Michael’s becoming The Black Flamingo allows him to transform into a more confident and fuller self. The character also serves as the result of Michael’s growth as a person and how he has learned about, and unlearned, things like internalized racism and Black queer lives of the past and the present.

Seeing how different experiences shaped the development of Michael’s drag character, “The Black Flamingo,” was thought-provoking and poignant.

Furthermore, some of the experiences that influenced “The Black Flamingo” also give the reader an interesting glimpse into LGBTQ culture in the United Kingdom. The contrast between a gay bar and a Black queer gay bar, and the homophobia casually tossed around by schoolchildren with terms like “bwatty bwoy,” show how complex the experiences of Black queer UK youth are, especially those of the children of immigrants. Michael has to unlearn a lot, especially regarding gender norms and heteronormativity. Neither completely fertile nor arid, UK LGBTQ culture is represented as something that Black queer people must navigate well in order to grow into the people they want to be.

Michael’s story also gives the reader a solid introduction to drag culture, with clear and creative explanations of what it is and what it isn’t. Since Michael is new to drag culture, the reader is able to learn about it alongside him. I love these lines that sum up what Michael wants from drag culture: “I’m just a man and I want to wear a dress and makeup onstage…. I’m a man and I want to be a free one.”

While The Black Flamingo is enjoyable as-is, it would have been interesting to see what the Jamaican side of Michael’s family thought of his queerness. Michael doesn’t mention his queerness to them at all, since he knows it’s illegal to be gay in Jamaica and that his family might have brought some of that prejudice with them to the UK. It is entirely possible that some of Michael’s family will not accept him. Yet given how completely Michael’s Greek mom accepts his queerness, it would have been nice to see at least one member of Michael’s Jamaican family do the same.

On the whole, The Black Flamingo is an electrifying, poetic declaration of identity. Through poetry, coming-of-age perspectives, and drag, the novel offers a triumphant tale of transformation and self-expression.

The Afro YA promotes black young adult authors and YA books with black characters, especially those that influence Pennington, an aspiring YA author who believes that black YA readers need diverse books, creators, and stories so that they don’t have to search for their experiences like she did.

Latonya Pennington is a poet and freelance pop culture critic. Their freelance work can also be found at PRIDE, Wear Your Voice magazine, and Black Sci-fi. As a poet, they have been published in Fiyah Lit magazine, Scribes of Nyota, and Argot magazine among others.

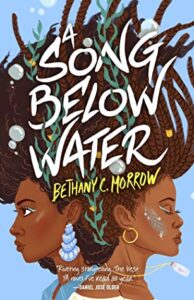

Tavia Phillips is a siren who must hide her powers in order to keep herself alive. Her best friend, Effie, is struggling with a painful past and strange happenings in the present. While they are trying to navigate their junior year of high school, a siren murder trial shakes Portland, Oregon, to the core. In the aftermath, Tavia and Effie must come together and come to terms with themselves.

Tavia Phillips is a siren who must hide her powers in order to keep herself alive. Her best friend, Effie, is struggling with a painful past and strange happenings in the present. While they are trying to navigate their junior year of high school, a siren murder trial shakes Portland, Oregon, to the core. In the aftermath, Tavia and Effie must come together and come to terms with themselves. This poem hasn’t appeared in any of my books, but my dream is that someone somewhere will make it into a print or broadside with art, and it will hang in coffee houses and kitchens above coffeemakers. If you’re the person who can make this happen, please do! I’d love to see it.

This poem hasn’t appeared in any of my books, but my dream is that someone somewhere will make it into a print or broadside with art, and it will hang in coffee houses and kitchens above coffeemakers. If you’re the person who can make this happen, please do! I’d love to see it.

Recent Comments